In this episode, I discuss the newly launched MethaneSAT — a satellite that can detect methane emissions on the ground — with Mark Brownstein of the Environmental Defense Fund. We cover how it came to be, its technical capacities, and the ways satellite detection might serve global efforts to reduce emissions.

Text transcript:

David Roberts

Recent years have seen the launch of several satellites that boast the ability to detect methane emissions on the Earth's surface from near orbit. The latest and most high-profile launch took place on March 4: MethaneSAT, a project long in development at the Environmental Defense Fund, is officially circling the planet.

MethaneSAT has technical capabilities beyond existing satellites and represents another big step toward a future in which all greenhouse gas emissions are visible and traceable to their source — a radical change from the situation we are in today, in which the majority of emissions are estimated, not measured directly.

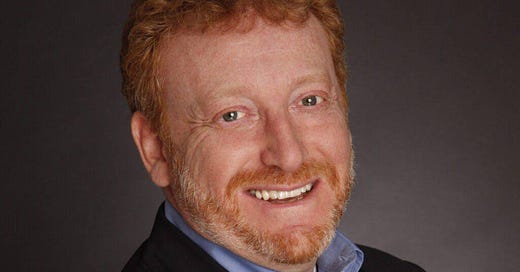

I wrote excitedly about the use of satellite imagery for emissions tracking way back in 2019 for Vox. To get a sense of what's changed and progressed since then, and what the future promises, I got in touch with Mark Brownstein, who leads the energy program at EDF.

We talked about the history of the MethaneSAT project, its technical capabilities, and the kinds of policies and campaigns it will enable. As a big believer in the power of transparency, I think this is one of the most exciting things going on in the climate world right now and I was geeked to learn more about it.

Okay, then, let's do this. Mark Brownstein of EDF, welcome to Volts. Thank you so much for coming.

Mark Brownstein

Dave, this is a bucket list for me to be on your show, so thanks.

David Roberts

Well, you need a better bucket list, my friend. Okay, there's a lot to talk about here with these satellites. What's the deal with these satellites? So let me just maybe start with a little bit of history. I know, I remember vaguely back in the early 2010s or something, the EDF launched a big thing where they were going to do a lot of methane monitoring, kind of like at the neighborhood level or the ground level. And then my vague understanding of that is that you guys discovered, "Hey, there's a lot more methane leaking than anybody thought or that anybody assumed. We need to do a lot more monitoring."

And then you set off on this quest to do a satellite. So just tell us a little bit about the history of how this MethaneSAT thing came about.

Mark Brownstein

Dave, that's exactly right. I mean, you don't wake up one morning and go, "Hey, I think I'll do a satellite and put it in space, and what will I look for? Oh, I know, methane!" This came out of work that we started really back in 2010. If you remember back in those days: it was the early days of the fracking revolution in the United States. Industry was making all sorts of grand claims about how this was the best thing since sliced bread and this was going to be a winner for the climate. And of course, Bob Howarth and others were beginning to raise questions about the methane footprint associated with this gas.

And our own chief scientist, Steve Hamburg, also was raising these concerns internally. But what became very clear to us early on was that no one really had a good handle on just how much emissions were coming out of these operations. Even now, to the present day, when companies report their methane pollution to the EPA, or for that matter, to the IPCC, they're using engineering calculations.

David Roberts

Oh, so they're not measuring their own emissions either?

Mark Brownstein

No.

David Roberts

No one's measuring emissions directly or was?

Mark Brownstein

No one was. Okay, and so there was this raging debate just exactly how much pollution was actually coming from these operations. We decided that rather than just get in the middle of the "he said, she said," that we would actually go out and do field measurements. And so, back in 2011, we started with Dave Allen at the University of Texas, actually going out and doing field measurements in the US. That led to a whole campaign to not only look at methane emissions from oil and gas fields from well sites, but compressor stations and gathering and processing facilities.

We even did work looking at methane emissions associated with city gas utility systems. And what we learned and what we published back in 2019 was the conclusion that, in fact, all of these engineering estimates were woefully underreporting emissions.

David Roberts

Shocker.

Mark Brownstein

That, in fact, emissions were 60% higher in reality than what was being reported to EPA by the industry using these engineering estimates that EPA had asked them to use, right. I mean, so this was both EPA and the industry just being way off the mark. We then subsequently went out and did similar kinds of studies in Canada. We did some in Mexico. We did some in Romania, in Eastern Europe, in Australia. Every time we've gone out and done these kinds of field studies, they always come back with the same basic finding: that actual emissions are, in fact, much higher than what's being reported.

Now, that then led us to conclude that there was a need to begin to get better information at a global scale. Of course, the oil and gas industry is a global industry. The United States is the world's largest producer of oil and gas. But I think, as anyone listening to this podcast knows, oil and gas is produced around the world. It was not going to be feasible for us to be able to use the same techniques that we were using in the United States and Canada in other parts of the world. Both because we couldn't get access to some places, and you can imagine what some of those places are, but also it'd be damn expensive and very time-consuming.

And so we concluded that a global challenge required a global tool, and that's where the idea of MethaneSAT was born. Steve Hamburg started having conversations with a guy named Steve Wofsy up at Harvard University, who is literally the world's expert of using satellites to assess environmental pollutants. And Dr. Wofsy told Steve, "Yeah, this would be possible. Never been done before, but it is possible to do." And so they started brainstorming what this satellite could look like. And that's how MethaneSAT was born.

David Roberts

And it's been like six years, they said, in development.

Mark Brownstein

Yeah.

David Roberts

Which kind of makes me wonder, because satellites have been around for a long time. Just getting something up there in orbit: very well understood. So I'm assuming that all the difficulty in development was in the detection and measuring technology.

Mark Brownstein

It's interesting because it's actually a combination of things. First of all, even if we had had this idea 15 or 20 years ago, the technology really wasn't there at that time to be able to do this. So this is a classic example of sort of right idea at right moment.

David Roberts

Yeah, this was exactly my question: what is that technology that developed to the point that we could use it? What is that exactly?

Mark Brownstein

It's a combination of things. I mean, first of all, the ability — 20 years ago, you couldn't enter into a commercial contract to put a satellite into space.

David Roberts

Right.

Mark Brownstein

That's changed, right? I mean, 20 years ago, space was largely the province of government space agencies. And as well, the basic technologies that go into building satellites, just like the technologies that have gone into making your iPhones ever more sophisticated, it's the same dynamic at work. And as well, the improvements in computing power and computing capability also matter because it's not just about the satellite. Right. MethaneSAT is a cool piece of hardware, for sure, but it has really complex and sophisticated algorithms associated with it that allow us to interpret the data that we're getting and be able to tie the emissions that we're seeing back to specific geographies and be able to do that on a relatively instantaneous and automated basis.

David Roberts

And Google had something to do with that, right? Like, Google's software is at work here.

Mark Brownstein

Yeah, so we entered into a partnership with Google and Google Earth. If you are able to discern a concentration of methane in the atmosphere, you need to be able to tie that concentration back to a particular geography in order to be able to gain some insights as to where this came from and then understanding also something about weather patterns and the atmosphere, also be able to interpolate the impact of the rate at which the emissions are coming out of that point. So the partnership with Google was very much about making sure that we had a good map on the ground of infrastructure to essentially correlate these emissions that we're seeing back to literally points on the map.

David Roberts

I feel like I'm asking a dumb question here, but how can you detect a concentration of methane in the air? Methane is invisible. I could be standing right next to a concentration in the air and I wouldn't know it. How do you see it? It's invisible, Mark.

Mark Brownstein

Well, MethaneSAT, at the end of the day, is a spectrometer. So what that means is basically, sunlight is reflected off the surface of the earth, and what you're basically doing is, and this is a very sort of layperson's way of expressing this, but it's discerning the molecules of methane in that column of light. And then additionally, through the algorithms, you're essentially assessing where that concentration of methane came from, knowing something about the wind speed and atmospheric pressure and so on and so forth, and also something about the rate at which that concentration was emitted.

David Roberts

And could we theoretically use spectrometers — I'm asking, like, dumb science 101 questions now — but could we discern other kinds of molecules in the air? What all can we detect with these things? Is there something special about methane in the air? Or is this the kind of thing where a spectrometer could tell you exactly the chemical composition of the air?

Mark Brownstein

I'm not going to pretend like I'm the world's greatest expert on spectrometry. That's the Steve Wofsy show, and he's well worth talking to, because he really does know just about everything there is to know about this. But what I've learned from him is that MethaneSAT not only has the capacity to discern molecules of methane in the atmosphere, but also has the ability to discern molecules of CO2.

David Roberts

Yes, that was my next question.

Mark Brownstein

And this is really an important point that I think a number of people have been sort of missing about this whole project, which is MethaneSAT really is the first time that we will have an instrument that is capable of giving us a relatively comprehensive picture of an actual concentration of greenhouse gas pollutants coming from a major industry. And so what it signals is that we're entering a world now where, for any greenhouse gas pollutant, we will start to be able to measure actual concentrations of that greenhouse gas pollutant in the atmosphere and also the actual emissions associated with individual industrial sectors. I mean, the simple fact of the matter is that everything that we have been doing and relying on for the last 30 years has been the product of emission estimates being reported to the IPCC.

David Roberts

Right.

Mark Brownstein

Now, for CO2, that's not such a bad thing, in the sense that it's relatively straightforward to calculate the CO2 emissions associated with burning fossil fuels. If you know something about the carbon content of the fuel and the efficiency with which it's burned, you can sort of come up with this. But for natural systems, for forests, for example, or for wetlands: no. And so we're on the cusp of sort of a revolution in how we understand the concentration of greenhouse gas pollutants in the atmosphere and how we can go about accurately measuring them and tying them back to sources.

MethaneSAT is just the beginning of a big change on the horizon.

David Roberts

Yeah, that's really wild. So no one is yet using satellites to detect CO2. That's all methane for now. But CO2 is on the docket.

Mark Brownstein

Right. And to be fair, there are plenty of satellites that are measuring concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere, but what they're not doing is they're not yet of the type that would allow you to tie those emissions back to sources. Right. And that is really where MethaneSAT, I think, is adding something new to the conversation, because this now becomes a tool to assess just how well the oil and gas industry is doing in managing the methane emissions associated with their operations. And that information is either going to tell a story of progress or it's going to tell a story of an industry lagging behind.

David Roberts

Yeah. But just to wrap up the technology question before we leave it behind. So kind of to summarize what's enabled this is: really good spectrometry, really good computing power, and algorithms that can take that data and tell you things about it, discern things from it, and cheaper satellites, basically. Like the combination of those three things.

Mark Brownstein

Enter into a commercial contract.

David Roberts

Right. And the fact that everybody's up in space now.

Mark Brownstein

It really is remarkable.

David Roberts

But it's my understanding that there are a number of methane detecting satellites.

Mark Brownstein

Yeah.

David Roberts

What are the different kinds, flavors here?

Mark Brownstein

On one end of the spectrum, you have what we call the mappers. These are satellites that have very wide field of views. They're not all that sensitive and they're not all that granular. So we've all seen the pictures in the newspaper of super emitter events over central Asia or in New Mexico. These mapper satellites are capable of giving us kind of a very broad scale global view of methane concentrations in the atmosphere and some sense as to where those big plumes of methane are coming from. Those are the mappers, and probably the most paradigmatic one of those is run by the European Space Agency, the Sentinel satellite, sometimes known as TROPOMI.

On the other end of the spectrum from the mappers, you have what we call kind of the point-and-shoot satellites. These satellites have a very narrow field of view, and oftentimes they have better sensitivity than the mappers, and they're really good when you know where to look. So a good example of this kind of technology is a company, is a private company out of Canada, out of Montreal called GHGSat. And this is a tool that's being used already by researchers, by government, and really even by industry to look to discern where there are big emissions from a particular facility.

David Roberts

So that's like a facility level view.

Mark Brownstein

I think of it more like a diagnostic tool, right? So, if I'm a major oil company and I want to know whether or not my facilities in a particular part of the world are leaking methane, I could enter into a contract with GHGSAT. If they had a satellite in that vicinity, they could fly over it and look at that geography and tell you, "Yeah, we see a big emission here, we see a big emission there," so on and so forth.

David Roberts

So, if you have the big, wide mappers and then you have the narrow point-and-shooters, what is the gap? What is MethaneSAT doing?

Mark Brownstein

MethaneSAT sort of sits in the middle of the mappers and kind of the point-and-shoot satellites. So, it's got a wide field of view, 200 kilometer by 200 kilometer. It has very fine pixelization within that. And so, the way to think of this is think of your big screen TV. You've got a big, wide TV, but then you've got very fine pixels that give you a very sharp picture, right? So, the pixelization within that 200 kilometer field of view is just about one kilometer by one kilometer. So, very fine resolution. Additionally, very high sensitivity.

We're capable of seeing emissions as low as five kg/hour or about two parts per billion of a background level.

David Roberts

Good grief.

Mark Brownstein

So, it gives you a very comprehensive picture of the emissions in that 200 kilometer by 200 kilometer area. So, we can't instantaneously map the whole world like a mapper can. Okay. We can't necessarily drill down and tell you specifically whether there's a big emission plume at a particular geographic location, but what we can tell you is we can give you really good information about the total amount of emissions coming from any production region in the world. We can see more of those emissions than either the mappers or the current point-and-shoot technologies can tell you.

We have a fine enough resolution that we can do a pretty good job of attributing what we're seeing back to a specific geography. So, we may not be able to tell you the specific well where the problem is coming from, but we can tell you it's somewhere in that area.

David Roberts

Like a one kilometer by one kilometer area? Because that's pretty tight. That's a small number of wells you're going to fit in that.

Mark Brownstein

That's exactly right. And then you could use your point-and-shoot technology, or you could use an aircraft, or you could use even a terrestrial system to go out and find it.

David Roberts

Are these different satellites, the mappers and the point-and-shoots and your satellite, are they coordinating their work here? Are they working together?

Mark Brownstein

Yeah, I mean, there's a really good, strong community of companies and satellite developers who are working together. So, GHGSAT and the European Space Agency, the Japanese space agency is going to be launching something called GOSAT-2. There is a project just behind us called Carbon Mapper, which is up and coming, is more like the point shoot technology of GHGSAT. And all of these folks are talking to each other and working together. One of the things that we've been doing in the six years since we've been developing the satellite is helping to build the community and the infrastructure that can make use of this data.

We have been working with the UN environment program to set up something called the International Methane Emissions Observatory. And the whole idea behind that entity, called IMEO, is that it becomes the central clearinghouse for everyone's data. Because at the end of the day, we're going to get the most comprehensive picture of methane emissions from the oil and gas industry and ultimately from the ag industry by taking advantage of the strengths of each one of these tools and putting them together to get the most comprehensive picture possible.

David Roberts

Some of these are private and some of them are public. Are they all willing to make their data public and share it with the UN and the world at large? Is it all open for anyone to look at?

Mark Brownstein

Well, different satellite sponsors have different business models, if you will. Obviously, the space agencies are sponsored by governments and they're there doing government sponsored research, which ostensibly is in the public interest. A company like GHGSAT is fundamentally a for-profit company. So, they are looking to provide a service to people who pay them to deliver information, but they are making at least a base level of data ultimately available because they believe that greater understanding of this issue and greater access to information is ultimately important.

David Roberts

So, who would pay? Who would be the customer? Would this be like a US, like a US oil driller would be like, "I want to know where in my operations the methane is."

Mark Brownstein

You may be familiar with the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative. This was something that twelve of the world's largest oil companies launched back in 2014 to create an initiative around energy transition and decarbonizing the oil and gas industry. They put together a $10 billion fund that they've been investing in cutting edge technologies that they believe are going to be useful to the energy transition. They have been an investor in GHGSAT and they have been using GHGSAT, these companies, to do diagnostic work, for example, in southern Iraq, where they've been seeing major sources of emissions coming from southern Iraq.

And then they're using that information to go in there and partner with the Basra oil company to find and fix those problems.

David Roberts

This is a cynical question, but why would an oil and gas company ever want this information to exist at all? Why — in what way does it benefit? Why wouldn't they just want ignorance to last as long as possible? What are they getting out of knowing these specifics?

Mark Brownstein

As you begin to work with the oil and gas industry, you come to understand that it's not a homogeneous group of folks. So, the household names, the Exxons, the Shells, the Mobiles, the Totals, they've got one set of motivations. There's a whole second set of players: national oil companies. Who actually are responsible for more than 50% of global oil- and gas-production, own two thirds of the total reserves. Saudi Aramco is probably the most famous one of these. ADNOC, the national oil company of the UAE, was a lot in the news last year because of the COP being held in the UAE.

But there are many, many national oil companies and they've got a different set of interests. What we often remind folks of is that methane is the core ingredient in natural gas. Every molecule of methane that goes into the atmosphere is not only a problem for the climate, it's a waste of an energy resource. National oil companies are constituted to make good use of the energy resource within their borders. If there's evidence that there's huge amounts of losses, then by definition that national oil company is failing in its core mission. And if they don't care, certainly their finance ministries care.

Their energy ministries care. You know, it's been very interesting, our conversations with stakeholders in Japan. Japan is highly dependent on natural gas. And of course, the geopolitics of recent years has put a lot of stress on global gas markets. And that has left Japan and others scrambling to secure new supply. We've worked both with the International Energy Agency and S&P Global to document the fact that the total amount of methane losses across the global oil and gas industry, if we were to recapture it, is enough gas to supply most of what Europe was otherwise buying from Russia.

Okay, it's a huge amount of energy resource, and of course, we and others want to hasten the transition away from gas dependence. But in the next couple of decades, as we work to do that, rather than drill new wells to meet that existing demand, let's make more efficient use of the gas that's already coming out of the ground. But that is being lost in venting and leaks and flaring.

David Roberts

But isn't flaring — my understanding of flaring is that they do that because it doesn't pencil out to capture it?

Mark Brownstein

There's a couple of reasons why — more than a couple of reasons. But two of the bigger reasons why you have flaring of gas: one is that the gas that's being produced is "associated" with oil. So in other words, you're drilling the well because you want the oil. And the economics of that well are driven by the price of the oil. Now, gas comes up along with it. If it's relatively easy for you to take that gas and put it to market, great, that's gravy. But if the infrastructure isn't there to make good use of that gas, if there isn't a ready market for it, companies would rather vent it or flare it than forego the revenues associated with drilling and producing the oil.

And so you have a lot of flares in places where the primary purpose of the drilling activity is for oil, and there's an underdeveloped infrastructure for taking that gas to market. So that's one problem that you have. Another is that sometimes the gas that you are producing is associated with oil, and it's also pretty remote, and so it's costly to build the infrastructure to get it to a place.

David Roberts

So detecting those kinds is not going to help you because they know more or less that those are happening.

Mark Brownstein

Well, it's not just satellite technology that has evolved over time. There's plenty of opportunities now to take the gas that's in relatively remote areas and on site, convert it to power generation — maybe for the oil production facilities that are around through small combustion turbines or whatnot — or to use it to produce fertilizer. So in the developing world, for example, natural gas is not just about power generation, it's also about fertilizer production. And when geopolitics roils the gas markets, it doesn't just create problems for energy users, it also creates follow-on problems for agriculture because of agriculture's dependence on fertilizers.

David Roberts

All right, so getting back to the satellites. So if you now combine all the mappers that are up there, all the point-and-shooters that are up there, and now MethaneSAT, how close are we to getting something like a comprehensive global view? Is that possible? Is it within reach? Is it close?

Mark Brownstein

I think that we're very close. MethaneSAT by itself will give us good information on at least 80% to 85% of total oil and gas operations.

David Roberts

No kidding?

Mark Brownstein

Yeah. And it'll take us somewhere between a year and a year and a half to build up that inventory, if you will. But if all goes according to plan, sometime in 2025, we will basically have the ability now to track emissions for 80-85% of all oil and gas operations and do it production basin by production basin. Right. So when the US oil and gas industry makes the claim that they're cleaner —

David Roberts

As they do.

Mark Brownstein

As they do. MethaneSAT will now provide the information to assess how true that claim is, and as importantly, be able to discern, "Well, how does the Permian compare to production in the Marcellus?"

How does the production in the Marcellus compare to production in the Bakken? These are all production basins within the United States. It's almost less important, in some ways, to have a national number than to have a number that is specifically ascribable to every production basin because that's the relevant commercial unit of measure, if you will, for the industry.

David Roberts

I guess I wonder a little bit about the geopolitics of this. Like, if I'm Putin and I hear that an American company is sending a satellite up into space and it's going to measure exactly how much my gas fields are leaking, and it's going to tell everybody that. It sounds like the kind of thing that would irritate a dictator with oil fields. Is there geopolitical tension around this?

Mark Brownstein

Look, I'm not naive. I'm sure there are some people out there who are listening to this right now, or who tuned into the launch last week and are beginning to wring their hands a little bit. But the way I describe it is this: If you're a student that goes to class, does all the problems, keeps up with the readings, you're not really all that worried about the final exam. And in some ways, you welcome the final exam because it sort of confirms the fact that you're on top of your game. Right? You like to see that.

David Roberts

I think you and I can agree that Putin and Russian oil companies are probably not A-students in this regard.

Mark Brownstein

All right, so if you're the kind of student that wants to spend your entire semester hanging out at the bar, in the coffee houses, or smoking shisha or whatever it is that you do, right, and you're not keeping up with the schoolwork. Yeah, the exam at the end of the semester is going to be stressful for you. But the point here is that this is in your control. Right. Every oil and gas operator globally, every major oil- and gas-producing country around the world, has it within their power to address these emissions. One of the many things that we've learned over the course of the ten years of working on this issue is we've learned something about the importance of measuring data as opposed to estimating it.

But we've also learned about the many ways in which it is possible to control these emissions. There's plenty of field studies that we've done where we've seen sites that have virtually no methane emissions. So what that tells us is it is perfectly possible to produce oil and gas, to transport oil and gas, with minimal methane emissions. And so, it is completely doable. The International Energy Agency talks about the fact that you could get at least a 75% reduction in methane emissions from the global oil and gas industry with technology that's available to the industry today. When we helped develop the first-ever set of comprehensive oil and gas methane regulations in Colorado back in 2014, it was very interesting to see that as those regulations came into force after 2014, that the vast majority of companies that were required to go out and find leaks found that they could actually fix something like 70 or 80% of what they found that day with a guy and a wrench.

David Roberts

And probably save money doing it.

Mark Brownstein

Yeah, and many of the companies will tell you that once they began to realize the magnitude of the challenge, in other words, that they had become so comfortable with their own estimates that they sort of lost sight of the fact that the estimates weren't giving them a true picture. But once they started to see that true picture and started getting after this stuff, yeah, there was money to be saved. And also stories about workers that were given handheld infrared cameras to go out and find and fix leaks, and they would compete with each other to see how many they could find, right?

I mean, there's all sorts of stories like that, but I don't want to get too rosy about it. I mean, the simple fact of the matter is that these emissions are damn high. The International Energy Agency now has been doing a methane tracker since I think, like 2019. The emissions remain stubbornly high.

David Roberts

Well, can I ask you a couple of questions about what we found so far? Obviously, the data from MethaneSAT is not, I mean, you just launched it, but there have been, as you said, some satellites up and there's been renewed efforts at measuring lately. So, a couple of questions about what we found. There's sort of famously, starting in around 2007, there's this big surge of methane emissions globally. Like the global concentrations of methane in the atmosphere started rising pretty sharply in 2007. And it's my understanding that no one totally understands why. And there's some debate: Is this the permafrost?

Is this some sort of natural thing? Is this wetlands decaying? Or is it — has something to do with fracking and the fracking boom? Is it more oil and gas? Do we know now, have we solved that mystery?

Mark Brownstein

To the best of my understanding: no, that's still an open question. And I often get asked the question, well, "Why are you guys focused so much on the oil and gas industry? What about the permafrost? Why aren't you worried about the permafrost?" Well, hell, yeah, I am worried about the permafrost. And it's exactly because I am worried about the permafrost that I'm focused on the oil and gas industry. Let's go back to basics here, right? Methane from human activities drives close to a third of the warming that our planet is experiencing right now. To the extent that methane is beginning to emerge from permafrost, because permafrost is beginning to warm, probably the single most impactful thing that you can do to slow that process down is to eliminate the methane emissions from things like the oil and gas industry.

Right? So it's precisely because I am worried about permafrost that I'm so urgently pushing on the need to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas industry.

David Roberts

Theoretically, is MethaneSAT going to solve this mystery?

Mark Brownstein

It's more complicated than that. But I do think that the creation of an institution like the International Methane Emissions Observatory, where you're gathering data from a variety of different tools, may help answer some of these bigger questions. MethaneSAT is fundamentally about creating accountability for emissions and having the ability to identify and reward good actors and identify and focus on those who are lagging behind. So, it is very much a tool about action. But, yeah, I'm sure there's stuff that we're going to learn along the way that will contribute to our larger sort of science knowledge.

But its primary purpose here is really about getting people to be aware, giving them information that they can act on, and being able to assess just how well we're doing in reducing a pollutant that we know, we know is driving close to a third of the warming our planet is experiencing right now.

David Roberts

Well, let me ask about actionable information, then because another big debate in this area, as I understand it, is it big, sort of like mega leaks that are contributing most to the problem, or is it the accumulation of small leaks in your sort of pipelines and distribution networks that are producing the bulk of this? Do we have any insight into that question yet?

Mark Brownstein

The ratio may vary from basin to basin. Okay, so we've taken the sensor that's similar to the one that we have on MethaneSAT; we've put it on an aircraft, and we have flown it over all of the production basins in the United States. And some of this data is going to be coming out rather soon. But one of the things that we've learned, for example, is that in the Uinta, which is in Utah, fully 80% of the total emissions that we saw coming from the oil and gas industry were from these sort of small, what I'll call kind of chronic sources, 80%.

Okay, and the Permian, maybe it's about 50%. I'm going off of memory here. So it's about 50%. And generally speaking, I think what we're finding is roughly less than half of the total emissions coming from any particular production basin are coming from these large super emitters, the stuff that's gotten attention in the press.

David Roberts

So is that good news or bad news? I would think sort of intuitively, it's easier if you just have one big leak to go fix it. Right. And it's harder to go find a bunch of small leaks. Is that right?

Mark Brownstein

Well, what it tells you is that to get the kind of reductions that we need and that we know we can get, we have to do both, right? So campaigns that exclusively focus on super emitters are incredibly important because these things are big opportunities, very cost effective to address. But by only focusing on them, you're dealing with only maybe half of the problem. So to get the kind of reductions that we need, you have to focus on the smaller sources. And candidly, up until this point, with the satellite technologies that are currently available, we haven't been able to see a lot of these smaller, more chronic leaks.

This is one of the areas where MethaneSAT is going to add something new to the party because of that high resolution and because of that sensitivity, current satellites allow you to see sort of the tip of the iceberg, the part of the iceberg sticking up above the water. Right, but as the captain of the Titanic can tell you, it's what's below the water that can kill you. And so we're going to help all of us better understand what's below the water.

David Roberts

So right now, your focus for the first year, or whatever, of MethaneS,AT or for the time being, is oil and gas production infrastructure; that leaves a lot of gas out. For instance, will these satellites be useful at all in detecting leaks of natural gas in the sort of residential system, the pipelines and holding tanks and furnaces and stuff that people use in neighborhoods and stuff?

Mark Brownstein

Yeah, so, as you could probably imagine, the more diffuse you go, the more complicated it gets. I'm not aware that there's any satellite technology that's going to be the killer app for utility system leaks or for discerning the number of home heating systems that are doing incomplete combustion. So that's the bad news. I think the good news is that, again, over the past ten plus years that we've been doing this work, we've worked with and in some cases helped to pioneer some of the technologies that are available. We did a number of years ago, again, we partnered up with Google, and we put methane sensors on their Google street mapping cars.

And we drove through Boston, we drove through Indianapolis, we drove through a number of urban areas and actually mapped leaks. And again —

David Roberts

Can I guess they're more common than we thought?

Mark Brownstein

Well, it depends; it depends. In Indianapolis, it was relatively — they had invested a lot of money over the past 20 years in revitalizing their gas system. They have very few leaks. Boston is a disaster. Right. But we were able to not only discern concentrations of methane at the street level, but again, with algorithms, we were able to assess the rate at which those leaks were happening. And this is information now that utilities can use and public service commissions can use in the United States to rationalize the amount of capital that's put into maintaining gas systems.

David Roberts

So a bunch of people want to know — well, like, for instance, coal mines. Like, coal mine methane is huge. I think it's, like, equal to oil and gas or something crazy like that. And then, of course, there's landfills, there's agriculture, so there's other big sources of methane. I know you're focusing on oil and gas now. Are there concrete plans to move outward from there?

Mark Brownstein

The simple answer is yes. One of our partners in this project is actually New Zealand. The New Zealand Space Agency is going to be mission control for operating the satellite for the duration. And we're working with scientists in New Zealand. They are working on developing the algorithms to take the methane set data that we're collecting on methane and essentially do for agriculture what we've been able to develop for oil and gas. So it's a harder task.

David Roberts

It's more diffuse in agriculture; that's why?

Mark Brownstein

It's more diffuse. And the stakeholders that you ultimately need to engage with to address the problem are much more — I mean, if the oil and gas industry has a certain amount of heterogeneity, well, the animal husbandry community around the world is radically heterogeneous compared to oil and gas. And I mentioned the methane air campaign that we were doing before: We did pick up a lot of information on major landfills. So we know, as a practical matter, that the tool can be used to address those sources as well. And of course, in the intervening six years, isn't just the UN's IMEO program, it's also the development of the Global Methane Hub, which is a consortium of philanthropy that is very much supporting work on oil and gas, but also supporting work on agriculture and landfills.

David Roberts

That would just be the same basic data, just running different types of algorithms on it?

Mark Brownstein

Yeah, it's a lot of it, but it's no small thing, right, to say that you just need a bunch of algorithms. Okay. Only a guy who majored in history and political theory, like, I can. Can sort of toss it off, like, "Oh, yeah, just do some algorithms."

David Roberts

Well, everybody's tossing around algorithms these days, right and left. I just figured they must be getting easier to make.

Mark Brownstein

No, it's tough stuff. People far smarter than me work on this.

David Roberts

And I threw out a call for questions on Twitter, and a disturbing number of them wanted me to ask you about farts. So I feel I would be letting my audience down if I didn't at least —

Mark Brownstein

Oh, man.

David Roberts

bring them up: Like a herd of cattle, breathing and farting methane; that's enough to pick up on a satellite?

Mark Brownstein

Okay, so for all you eight-year-olds out there, right —

David Roberts

Thank you. Thank you for indulging.

Mark Brownstein

It's not the farts, it's the burps.

David Roberts

That's the wet blanket that always comes out here.

Mark Brownstein

It's the burps. And that is why so many strategies associated with addressing methane from cattle are focused on changing what they eat. Okay?

David Roberts

Yeah.

Mark Brownstein

I mean, if you have a constant diet of Doritos and beer, you get pretty gassy, right? So cows, if they're eating a lot of corn, which they're not really designed to do, they get pretty gassy. And so if you feed them different stuff, they're less burpy. And it turns out you can reduce emissions from cattle by at least 15% just by changing their diet.

David Roberts

So in theory, MethaneSAT could point its cameras, its spectrometers at two different herds of cattle and detect the fine differences in methane concentrations above one versus the other.

Mark Brownstein

This is where I would sort of take a lifeline here and call our colleagues in New Zealand. But, yeah, it has to be a big enough concentration of activity.

David Roberts

The final question is how — this is all in some way or another part of this Bloomberg. Tell me a little bit about the Bloomberg Philanthropies watchdog project and how MethaneSAT fits into that picture.

Mark Brownstein

Yeah, so one of the really important initiatives that came out of COP 28 — so a lot of COP 28 was very much about will the world commit itself to energy transition, to getting off fossil fuels, and that rightly was a big focus. But another really big initiative that occurred was this oil and gas decarbonization charter, which is now comprised of over 52 companies, many of them national oil companies — to go back to what I was saying before — who, among other things, have committed to significant methane reductions in the next five years. They've committed to near zero methane by the end of 2030.

And if you look at the details, it works out to roughly a 90% reduction that they'll be working to achieve in the next five years. So Bloomberg Philanthropies with us and with the International Energy Agency and the UN's International Methane Emission Observatory are going to work together to develop the data that will assess how well these companies are doing and meeting their commitment. And not just focus on the companies that have made the commitment, but also provide some information about the companies that have yet to commit. Back to your earlier point, we don't want to create a perverse incentive for companies to stay away from doing the right thing.

So we don't just want to focus on the companies that have made a commitment and allow others to stay in the shadow, but we do want to use this data to create some yardsticks for how well these companies are doing. And I'm encouraged by the fact that a number of the companies that I've talked to sort of welcome it in the spirit that I was saying earlier. Right. If you're going to go to the effort of addressing your methane emissions, you want recognition for the work that you're doing. And most of these companies are sophisticated enough to know that the public's trust in them, in the industry is something less than zero.

And so, they really are looking for independent third-party validation of the work that they're doing. We can provide that.

David Roberts

Lately, there's been some controversy about this notion of certified gas: This notion that you can offer customers this sort of special grade of natural gas that's very vaguely greener than some other form of natural gas. And my understanding of that is that it's mostly kind of BS at this point. I'm wondering if I can see the information from the satellites being used like that by natural gas companies to sort of give an imprimatur of sort of like greenness, cleanness to their natural gas. Have you thought at all about how to avoid getting sucked up in that?

Or how to avoid having your data sucked up in that?

Mark Brownstein

No, for sure. One of the significant initiatives that has sort of come to fruition in the last few years — one of them is the US finalizing oil and gas regulations that was also announced at COP 28. And that is really a big deal because the US is the world's largest oil and gas producer, and US regulation does sort of serve as a benchmark for practices around the world. So it's a big deal. And of course, this data will help with the implementation of those regulations and frankly, help hold states and the federal government accountable for enforcement.

Right, we've talked a lot about holding industry accountable. This kind of data is also going to hold countries accountable. And in Europe, they also are in the process of finalizing a package of measures, one of which is to require anyone selling gas into the European Union to disclose the methane emissions associated with the gas that's being sold.

David Roberts

Oh, and that includes, presumably, LNG imports.

Mark Brownstein

So the data from MethaneSAT, I think, will feed into that.

David Roberts

Interesting. So this question about how dirty is LNG, which is a very big fight right now, how many leaks are there in the pipelines? How much is involved in compression and all that? We're going to have to answer those questions statutorily, then, in order to sell that into Europe?

Mark Brownstein

I mean, anyone selling into Europe is going to have to be able to provide information. I think MethaneSAT is going to — I mean Europe has yet to write the regulations to implement the requirement — but I would imagine that the data that we're producing, because it is so comprehensive, is going to very much inform that requirement. JERA, which is a consortium of Japanese utilities that is responsible for buying 25% of the total gas that's consumed in Japan, is also now launching an initiative in a similar vein, to develop reporting requirements for the gas that's being sold to them.

And they're doing that in partnership with KOGAS, which is the Korean gas utility. So customers, major customers, are beginning to ask this question, right, "What is the methane emission associated with the gas that I am purchasing?" And so, this data will help inform that.

David Roberts

Say we're looking out five to ten years: there will probably be more satellites, we'll probably have a better handle on how to interpret the data, we'll probably have a more — the thing will have circled the earth several thousand times by then, and we'll probably have a more comprehensive picture. Do you think we're really going to get to a place where all the world's methane emissions are tracked and assigned responsibility to a party? Like, is it going to be comprehensive at some point?

Mark Brownstein

So MethaneSAT orbits the Earth 15 times a day, so it's going to be a very robust data set. I can say that in the next couple of years, there may be a period where it actually gets worse before it gets better. I mean, keep in mind that up until this point, everything that we've understood about methane emissions from the oil and gas industry has come largely from reported data using engineering estimates. So as we start to get more and better actual data, the likelihood is that the emissions are going to appear to be going up, because frankly, we're just getting a clearer picture.

David Roberts

So the emissions picture will get worse, but the data picture, the tracking picture, is just going to get better and better.

Mark Brownstein

And because of regulatory efforts on the part of the US and Canada and some of the work that's going on in China because of the industry's own commitments, motivated in part by wanting to appear cleaner and greener, but also because they're trying to make better use of the resource that they're pulling out of the ground. I mean, there's complicated motivations there. But yes, this data, I believe, will, over the next five years, significantly drive down methane pollution from the oil and gas industry, and that in turn will have an appreciable impact, so the science tells us, on the rate of warming on our planet.

David Roberts

More of my question was, are we going to get a comprehensive picture of global methane from everywhere? like there's no technical barrier, in other words, to being able to trace basically all the world's methane?

Mark Brownstein

No, it goes back to what I was — it was going back to what I was saying before. I mean, MethaneSAT, this — MethaneSAT is a little bit like Sputnik. It's really the beginning of something, right? It's the beginning of saying that we have the technology to actually measure industrial and even nonindustrial climate pollutants. And that technology is in the hands of civil society as much as it is in the hands of industry and government. So it's democratized. And I do think that over time, it will revolutionize not only how we talk about these issues, but it'll revolutionize the progress that we can make in addressing these problems.

David Roberts

I guess that's what I'd like to leave people with. It's just like you get into the details of this in that satellite or this in that field or whatever, but looking forward, having a measured rather than estimated database of all the world's greenhouse gas emissions and where they're coming from and who's responsible for them is really a fundamental change from what we have today. It's really going to be a new world.

Mark Brownstein

It's Peter Drucker 101, right? You can't manage what you don't measure.

David Roberts

Yeah. All right, well, this is awesome, Mark. Thanks so much for this. And congrats to you guys for pushing that rock all the way up the hill and off the hill and into space, I guess. Whatever the metaphor is, congrats on all your work on this and for getting it up there.

Mark Brownstein

Dave, thanks for taking interest in it.

David Roberts

Thank you for listening to the Volts podcast. It is ad-free, powered entirely by listeners like you. If you value conversations like this, please consider becoming a paid Volts subscriber at volts.wtf. Yes, that's volts.wtf. So that I can continue doing this work. Thank you so much and I'll see you next time.

Share this post