In May 2019, I wrote in Vox that “one weird trick can help any state or city pass clean energy policy.” Spoiler: the one weird trick is electing Democrats.

My home state of Washington elected a whole mess of Democrats over the last several cycles and it is paying off handsomely. Without much national attention, the last few years have seen Washington quietly put into place the most comprehensive and ambitious slate of climate and energy policies of any US state. Yes, I’m talking to you, California.

The legislature just passed a carbon cap that will reduce economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions 95 percent by 2050 (it awaits Gov. Jay Inslee’s signature). I want to talk about that bill, but first, to understand its significance, we need to quickly review all the other stuff the Washington legislature has been up to lately.

Let’s run through the last three years. It’s a lot. (And this is only the climate stuff; there’s much more: police reform, a capital gains tax, reduction in penalties for drug possession, etc.)

In 2019, the legislature passed:

the Clean Energy Transformation Act (CETA), the most significant energy bill in state history, which will require state utilities to reach carbon neutrality by 2030 and 100 percent self-generated carbon-free electricity by 2045; it also contains a bunch of sexy utility business-model reforms;

the Clean Buildings bill, a first-in-the-nation program that requires large commercial building owners to address the energy efficiency of their existing buildings;

a bill on hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which will phase out dangerous ozone-depleting (and climate-warming) aerosols, foams, and refrigerants (making Washington the second state, after California, to do so); and

HB 2042, which puts about $170 million toward transportation electrification, through tax incentives for mid-market EVs, money for charging stations, and money to transit agencies to electrify buses.

In 2020, it passed:

SB 5811, which adopts California’s Zero-Emissions Vehicle (ZEV) program and California’s Advanced Clean Truck Rule, requiring rising sales of ZEV passenger vehicles and heavy- and medium-duty trucks, respectively; and

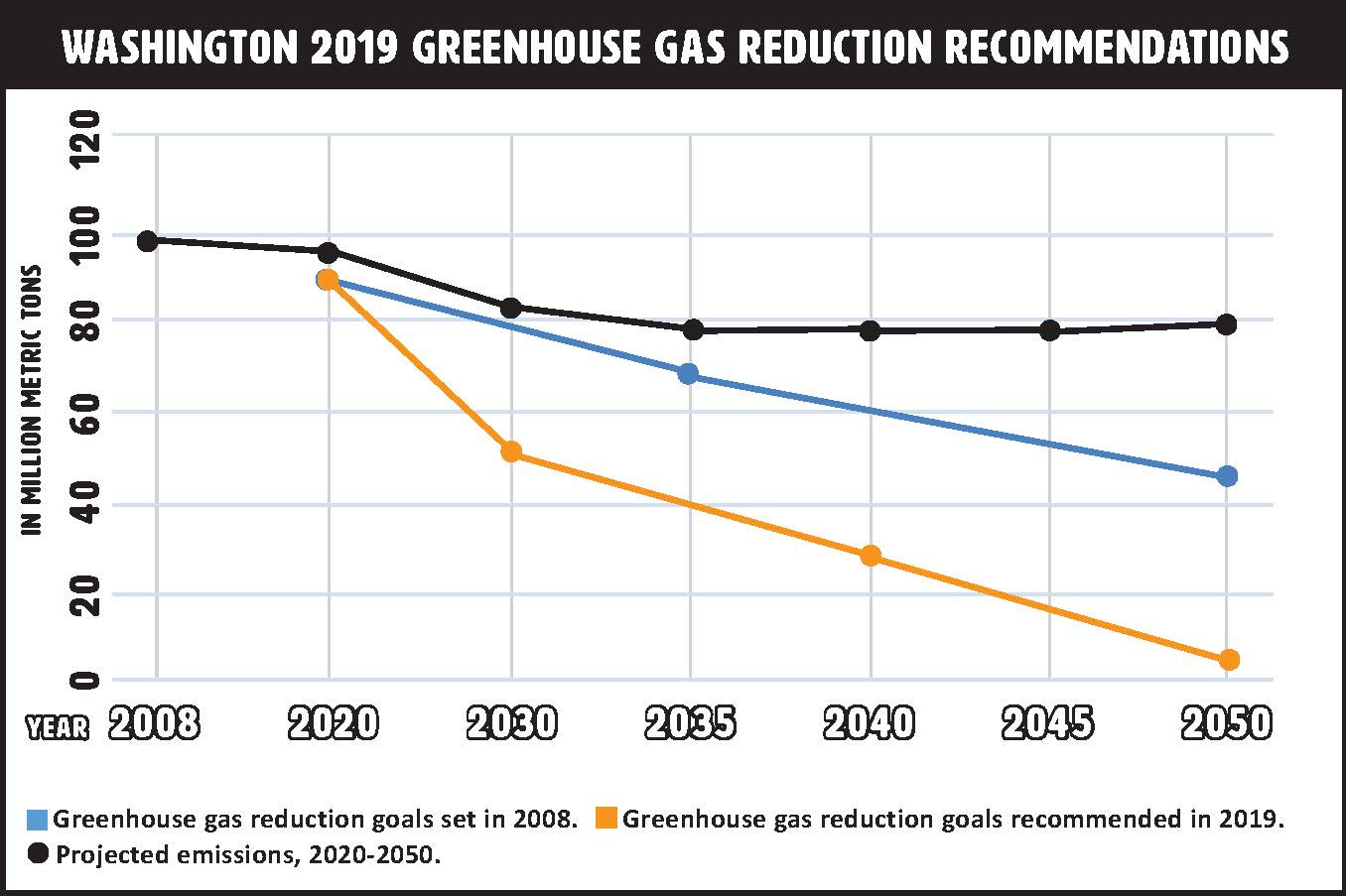

an update of the state’s greenhouse gas emission goals: 45 percent reduction from 1990 levels by 2030, 70 percent by 2040, and 95 percent/net-zero by 2050.

In 2021 so far, it has passed:

HB 1050, another HFC bill that goes beyond recently adopted federal standards;

HB 1084, the Healthy Homes and Clean Buildings Act, which would take a number of steps to gradually phase out natural gas utility service and boost building electrification [Correction: 1084 did not actually pass; it died in the Appropriations Committee, but several of its provisions passed via the state budget]; and

HB 1091, which would establish a clean fuels standard (CFS) that gradually reduces the carbon content of liquid fuels in the state, similar to laws already in place in California, Oregon, and British Columbia (making a declining carbon standard for fuels the law of the land from the Mexican border to the Yukon). This has been a long fight in Washington — the CFS is one of Big Oil’s least-favorite policies — and this is the third attempt to pass it, so victory is sweet.

So, the legislature has already passed laws specific to electricity, transportation, buildings, and fuels. All of this activity sets the context for last week’s finale: SB 5126, the Climate Commitment Act (CCA — here’s the bill text).

I wrote last year that carbon pricing has been dethroned in left-leaning carbon policy circles, in favor of industrial policy — sector-specific standards, investments, and justice (SIJ). But the dream of carbon pricing never died in the hearts of Jay Inslee and Washington legislators. The CCA is a “cap-and-invest” program that would impose a declining cap on emissions and distribute allowances under the cap, thereby placing an escalating price on carbon.

There’s lots to say about this, but the first thing to note is that this is not carbon pricing instead of SIJ — note all the sector-specific policies passed before and alongside it. It is carbon pricing as a complement, part of a comprehensive suite of carbon policies.

Note also that this bill comes at the tail end of a long record of failure on carbon pricing in Washington, including two citizen-led ballot initiatives, one based on economists’ recommendations and one based on the environmental left’s recommendations, both of which were defeated. There’s a lot of history here.

Politically, there are two salient facts bounding the bill.

On the downside, implementation of both the CFS and the CCA is contingent on the passage of a transportation package containing a boost in the gas tax of at least five cents per gallon. Many state climate activists are angry about this, because in its current condition, the transportation package is highway-heavy. (I’ll get into this more later.)

On the upside, once it is in effect, the CCA is authorized to stay in effect until its emission goals are reached. This is a really big deal: there won’t be a big legislative fight over re-authorization like there was in California in 2017, which weakened that state’s program. There is no sunset or time limit on the CCA. It stays in place until the state is net-zero. A declining cap is now the status quo, and it’s always more difficult to pass a new bill to change the status quo than it is to keep it in place.

Before we get too deep in the politics, though, let’s look at what the CCA does. It adopts the same broad outlines as California’s cap-and-trade system, but with this guiding principle, as articulated to the Seattle Times by state Sen. Reuven Carlyle (D-Seattle), the bill’s key Senate architect: “I had a check list, and I made sure in my own head that we addressed these criticisms and weaknesses of the California bill, and not just danced around them.”

Cap-and-invest will issue a declining number of allowances

The CCA is a program to achieve the state’s carbon targets, as updated last year: 45 percent reduction from 1990 levels by 2030, 70 percent by 2040, and 95 percent/net-zero by 2050.

Keep in mind: this is not just the electricity sector. It’s electricity and transportation and oil and gas and more — somewhere between 75 and 80 percent of the state’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Only California has comparable economy-wide aspirations, but Washington’s rate of reductions will need to be much more rapid than California’s to reach its targets. In terms of the sheer pace of change to which a state has committed, Washington has taken the lead.

With a few exceptions, the cap will cover all entities that emit at least 25,000 tons of energy, process, or landfill emissions a year — around 100 entities total. Each year, a declining number of allowances will be issued. Most of them will be distributed via auction (sold to raise revenue for the state), with a few exceptions.

Electric utilities are already covered by CETA, so they get their allowances free. They can use their allowances for compliance and, if they reduce emissions ahead of schedule, auction off the remainder. Any benefits from those auctions are to be used “for the benefit of ratepayers, with the first priority the mitigation of any rate impacts to low-income customers.”

Natural gas utilities get free allowances equal to their emissions the first year, with that number declining by about 6.5 percent a year through 2030, commensurate with the cap. Starting in 2023, natgas utilities must auction 65 percent of those free allowances, with the number by rising by 5 percent a year up to 100 percent. The auction proceeds must be returned to customers “by providing nonvolumetric [equal for each customer] credits on ratepayer utility bills, prioritizing low-income customers, or used to minimize cost impacts on low-income, residential, and small business customers through actions that include, but are not limited to, weatherization, decarbonization, conservation and efficiency services, and bill assistance.” But there’s a twist: excepting low-income households, only households that are already connected to the natural gas system when the bill goes into effect can receive these rebates. Subsequent hookups do not, a significant disincentive California doesn’t have.

Finally, so-called energy-intensive trade-exposed (EITE) entities — industries where marginal increases in energy costs could prove a competitive disadvantage and potentially push them out of state — are not exempt from the cap. They will receive a steadily declining share of free allowances through 2035, based on their output.

Note: some environmental-justice activists have criticized this provision, but a) the carbon-tax bill the EJ community supported earlier this session, Washington STRONG, would exempt all EITE entities from its cap, forever, b) EITE entities can have their access to offsets cut off if they are harming local air quality, and c) the air-quality regulations in the CCA serve as a backstop for local air quality. This is about as good as you’ll find any state doing on EITE businesses.

The price of allowances will have a floor and a ceiling

The price of allowances, as established by auctions, will have a “collar,” meaning it will have a rising floor (to ensure the program produces reliable revenue) and a rising ceiling (to make sure it doesn’t get too expensive). The ceiling will take the form of an allowance price containment reserve, which basically means that if the price hits the ceiling, unlimited allowances at that price can be released from the reserve until prices go back down.

The price collar will effectively cause the system to behave a little more like a carbon tax, with price fluctuations confined to a predictable range.

There will also be an “emissions containment reserve,” set to a trigger price, that will allow the department to withdraw subsets of allowances from the system if the targets are not being met. (For more on emissions containment reserves, see this post from Resources for the Future.)

The state Department of Ecology will set the floor, ceiling, and trigger prices through rulemakings involving public and stakeholder input. In 2027, 2035, 2040, and 2050 — and whenever else it elects to — the department will review whether the program is on track to meet its targets and take any corrective action necessary. For instance, in the event of oversupply of allowances, a problem that bedevils the California system, the department can withdraw allowances from the system to push the price as high as necessary to get on the right trajectory.

Offsets will come in under the cap

Regulated entities may meet 8 percent of their compliance obligations through carbon offsets in the first compliance period (2023-2026); from then on, it is 6 percent. Of those offsets, 3 and then 2 percent respectively must go to projects on tribal lands; 50 and then 75 percent of the benefits, respectively, must be within Washington state.

Offsets are a huge source of controversy, in this system as in all systems where they play a role. A recent blockbuster investigation by ProPublica revealed that California’s biggest forestry offset programs are basically bogus — failing to reduce emissions and blowing the state’s carbon budget.

The dangers of offsets — explained in more detail in my interview with energy analysts Danny Cullenward and David Victor — are very real, but the bill contains a few key provisions that reduce those risks.

First and most importantly, unlike in California, offsets in Washington’s system are beneath the cap. This is a tricky concept to get your head around, so let me walk through some idealized examples.

Say, in a California-style system, the state’s emissions limit for the year is 1,000 tons. It allows 8 percent of compliance via offsets, so in addition to issuing 1,000 allowances, it allows 80 offset credits.

Note: there are now 1,080 tons worth of compliance instruments on the market (allowances + offsets). However, California believes that each offset represents a ton of carbon reduced elsewhere, outside the covered sectors. So 1,080 tons of compliance instruments - 80 tons of carbon reduced elsewhere = 1,000 tons, the state emissions limit. So far so good.

However! If the 80 offsets turn out to be bogus — if they don’t represent real carbon reductions elsewhere in the economy — then the system will net out at 1,080 tons of emissions, blowing past the state’s purported limit.

That, basically, is what critics say has been happening in California: because so many of the millions and millions of tons of offsets in the system are bogus, the state is actually permitting emissions well above its stated limits.

Washington legislators learned from California’s example and designed their system differently.

Say Washington’s emissions limit for the year is 1,000 tons. It also allows 8 percent compliance via offsets. However, its offsets are beneath the cap, meaning the state will issue 920 allowances and allow 80 offsets — a total of 1,000 tons worth of compliance instruments.

If all 80 offsets are bogus, then the state comes in at its limit: 1,000 tons. If the 80 offsets are valid, if they represent actual emission reductions outside the covered sectors, then they push emissions below the statutory cap. The system will actually have netted out at 920 tons of emissions, well under the state limit.

This is worth repeating: in the Washington system, insofar as offsets represent valid emission reductions, they are effectively a bonus, over and above the reductions required by statute. (This could help push the system to net-zero eventually.) Because the Washington system doesn’t rely on the validity of offsets to hit its caps, some of the political pressure is taken off of them.

That’s the first thing. The second thing is that the CCA directly addresses the long-standing concern over “hot spots.” The concern is that some heavily polluting facilities, often located in low-income or minority neighborhoods, will buy tons of cheap offsets and continue to pollute. The CCA — in addition to setting up a whole apparatus to measure local air quality and screen for vulnerable communities — says that if the state determines a particular facility is harming an “overburdened community,” it can restrict the facility’s access to offsets (a provision also absent in California).

Third, the Department of Ecology will be charged with determining which of California’s offset protocols to accept; it is not required to accept them all.

Critics of offsets have long said that the incentives are inevitably skewed in these systems: offset providers want lax standards so they can sell in bulk, regulated entities want lax standards because cheap offsets bring down the overall cost of compliance; politicians want lax standards because they also benefit from the optics of cheap compliance. Regulators, the only participants with an interest in maintaining standards, are under constant pressure.

It’s definitely true that the success of Washington’s program, on offsets and elsewhere, will depend on judicious action from future regulators. But that’s true of any system.

The revenue will go to climate mitigation and adaptation

Auctioning allowances every year will bring in billions of dollars in state revenue, the exact level depending on the price they bring. The state estimates that, if allowances sell at the California floor price, they will raise around $500 million a year, rising up to the high 600s over time — about $8 billion total through 2037. In reality, the Department of Ecology will set its own floor and in practice the price is likely to exceed it, given Washington’s ambitions.

Here’s how the revenue is allocated.

First, between the start of the cap-and-invest program and 2037, $5.2 billion of CCA revenue will go to transportation projects that reduce carbon emissions, mostly transit but also electrification, including electrification of Washington ferries (a huge win for local air quality).

We will get into the controversy over Washington’s transportation package later — remember, implementation of the CCA is contingent on its passage — but it is worth emphasizing that the CCA itself will spend roughly five times what the last transportation package allocated for transportation decarbonization projects. From 2037 on, 50 percent of CCA revenue will go to such projects. None of these funds can go to roads.

Second, every two years, $20 million will go to the Air Quality and Health Disparities Improvement Account (see below).

Third, the remaining funds — around $3 billion, assuming California’s floor price — will go to the Climate Investment Account, which will divide it as follows:

75 percent to the Climate Commitment Account, which will fund climate mitigation and some adaptation projects; it will also set aside $250 million to help relocate tribal communities threatened by sea-level rise; and

25 percent to the Natural Climate Solutions Account, which is dedicated to natural resources management and resilience.

All of the Climate Investment Account spending is subject to high labor standards, like the money spent in CETA (more on that here). The intent is to use the investments to create high-quality in-state union jobs.

Air-quality standards and targeted investments will address environmental justice

There are provisions throughout the CCA related to environmental justice.

First, one of the objections EJ communities often have to cap-and-trade is that it doesn’t guarantee improvement in local air quality, especially in overburdened communities. The CCA addresses this in Section 3, which sets up a system for local air-quality monitoring and regulation.

The state will identify overburdened communities using a tool like the Washington Environmental Health Disparities Map (which grades communities on over a dozen metrics) and deploy air-monitoring systems in the identified communities — something Washington, like many states, now lacks.

It will direct state and local air agencies to adopt new standards and regulations such that the overburdened communities either meet federal National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) or have air quality equal to nearby communities, whichever is more protective. Since all of Washington complies with NAAQS, these standards will go beyond federal air quality standards to specifically identify and eliminate wide disparities often based on class and race.

Every two years, the Department of Ecology will review the state’s progress to ensure that criteria pollutants in overburdened communities are declining on schedule.

Second, all the investments made with CCA revenue must target:

at least 35 percent to overburdened communities, with a target of 40 percent, and

and additional 10 percent to projects sponsored by tribal nations.

In California, a similar provision has meant roughly $3 billion invested in that state’s overburdened communities since 2014. Now Washington’s overburdened communities will receive a steady stream of investment as well.

Third, Washington’s Environmental Justice Council — created by the Healthy Environment for All (HEAL) Act, also passed this year — will provide oversight on the design of the program, the revenue, and any plans to link the system to California’s. (The council is a 12-member group, appointed by the governor and approved by the Senate, drawn from affected communities and state agencies.)

The state is also instructed to create a tribal consultation framework and ensure that tribes are involved in all Climate Investment Account spending decisions that affect tribal lands. (Tribes can halt projects if such consultation hasn’t taken place.)

So, the bill contains a combination of specific air-quality standards for overburdened communities, revenue for overburdened communities, and formal environmental-justice oversight of design and revenue decisions. We’ll touch more on the politics around this below.

Linking to California could be sketchy

Washington may eventually want to link its system to California’s, which is a politically dicey prospect, given familiar criticisms of that state’s system. To do so, the two states would have to agree on mutual exchange of allowances, align their price floors and ceilings, and integrate their auction systems, among other things.

Section 24 of the CCA instructs the Department of Ecology to analyze whether a link would do any harm to Washington’s system. Any linkage must not only integrate the systems properly, it must ensure that:

the jurisdiction being linked to has environmental-justice provisions in place to get revenue to overburdened communities,

the linkage will not harm overburdened communities in either jurisdiction,

the linkage will not harm Washington’s ability to hit its targets, and

Washington retains “all legal and policymaking authority over its program design and enforcement.”

That’s a pretty stiff set of requirements, and it’s an open question whether a linkage with California can meet them any time soon, given that state’s problems with oversupply and local air-quality concentrations. (More on that below.)

The politics around the CCA are pretty good, but there are objections

The nature of the news cycle these days is that stories come and go and are forgotten in a matter of hours. The passage of these landmark climate and energy bills is probably going to see the same fate — it will be gone from the headlines long before you read this, insofar as it got any headlines at all. (This should teach Democratic lawmakers something: they can pass big ambitious policies and people will barely register that it happened. Might as well let loose and pass more!)

Most people, if they noticed the bill passing at all, felt happy that something was getting done. Climate action is, after all, extremely popular. Among those engaged with the process, however, there has been some pushback, falling into three buckets.

1. Some urbanists hate the transportation linkage.

As I said in the intro, the CFS and the CCA have both passed, but their implementation is contingent on the passage of a transportation package (containing a gas tax of at least five cents a gallon).

Some Seattle urbanists are upset about the state of that transportation package; they believe it spends too much on highways, undercutting the CCA’s goals. They are therefore opposed to the linkage, and want Gov. Jay Inslee — who has a line-item veto — to strike it from the bill and allow the CCA to be implemented without restrictions. (That would severely piss off several moderate Democrats in the Senate.)

One thing to note on this is that all highway spending is not equal. Big chunks of the Washington highway budget will be taken up by court-mandated repair of culverts (to help fish). And there are lots of projects — like the new Columbia River Crossing bridge, which will include light rail — that most everyone agrees are necessary.

More importantly, through a twist of Washington law, the CFS and CCA will likely prevent billions of dollars in road spending. The use of bonding to borrow money for road spending requires a 60 percent majority in the Washington legislature, which means it will require several Republican votes. And Republicans are absolutely not going to vote for a transportation package that triggers the CFS and the CCA, two policies they passionately hate. That means no Republican votes and no bonding, which will sharply curtail, by several billion, the amount of money the transportation package can devote to roads.

And finally, remember, the CCA will put $5.2 billion toward transportation decarbonization, five times what the last transportation package spent on that, none of which can go to roads.

It seems to me that the benefits of the bill, in transportation alone, vastly outweigh the harms of a few highway-widening projects, irksome as they are.

2. Some environmental justice groups oppose cap-and-trade.

The state environmental justice community is divided on the CCA. Groups like Puget Sound Sage and Front and Centered have spoken out against it, but it has received support from 20 state tribes, El Centro de la Raza, the Washington Black Lives Matter Alliance, and Washington Build Back Black Alliance.

The opposition arises mainly from opposition to cap-and-trade itself, which some EJ activists believe is inherently inferior to a carbon tax like the 2018 state ballot initiative (1631) or Washington STRONG. To my mind, most of their critiques — especially around local air quality and participation — are directly answered by provisions in the bill. And some, like the idea that cap-and-invest allows companies to “pay to pollute,” are more true of the carbon taxes they support (which contain no mandatory emission reductions).

But make up your own mind: the Sage and F&C essays make the case against; Vlad Gutman-Britten of Climate Solutions addresses the objections at length here.

3. Some wonks worry about hooking up with California.

There’s long been a strain of thought in Washington that hitching up to the much larger California carbon market will effectively put California in charge of Washington policy. That critique used to come from the right, but lately there have been versions of it on the left as well.

There are two basic worries. The first is that California’s offset protocols are garbage and if Washington adopts them it will flood its system with bogus carbon reductions. The second is that California’s system suffers from chronic oversupply of allowances. The oversupply suppresses prices, and a governor facing a recall election and needing the support of the building trades is not going to support reform that raises prices any time soon. That could drag down Washington’s prices.

To some extent, these objections are answered in the bill. Offsets are below the cap, so the risks are lower; the Department of Ecology is not required to adopt all of California’s offset protocols, it can independently assess them; and the criteria for linkage specifically include that it not suppress prices.

Nonetheless, there is some tension here. There will be pressure to link the systems, to hold prices down in Washington. (Unlinked systems are, by some analyses, three times the cost of linked systems.) But it’s not totally clear how, once linked, Washington can enforce its own standards.

Since linkage won’t happen until the middle of the decade at the soonest, the best-case scenario is that California wrings some of the oversupply out of its system by then. And Washington linking could actually help lift prices in California — Washington will represent a lot of demand, given the steepness of its proposed emissions trajectory.

Washington is kicking ass

All of these objections are worth taking seriously, but in my judgment, on balance, Washington’s new bill — or more broadly, the comprehensive suite of policies the state has constructed — is overwhelmingly worth celebrating. Among other things, the CCA will bring billions in investment and new economic growth to the state, along with hundreds of thousands of new jobs.

Given all the scorn heaped on Washington legislators over the last decade, especially by climate advocates (including me), it is worth noting that credit for the CCA goes largely to legislators, negotiating directly with one another. They finally got sick of Washington fucking around on climate pricing, pulled together the lessons of previous attempts (and California’s example), hashed out a bill enough Democrats could agree to, and passed it. And they did a good job: the wonky i’s are dotted and t’s crossed.

Every success has many parents, and this one is no different, but special credit goes to Representative Joe Fitzgibbon in the House and Senator Reuven Carlyle in the Senate, who by all accounts (and I mean all accounts — one or both were praised by everyone I contacted, even some bill opponents) were central to coalition-building around these bills and improving them as they moved through the process.

Once Inslee signs the CFS and the CCA and a transportation package passes, both of which most observers expect in relatively short order, Washington will have the full suite: legally enforceable programs and standards in place to decarbonize electricity, transportation, and buildings, and in addition to that — as a complement, not an alternative — a declining cap that ensures the rapid emission reductions the state needs to meet its targets.

The Washington legislature is showing Democrats across the country that climate politics are good politics, that voters respond to big climate ambition. Now it’s up to Washington to show other states that reducing carbon emissions is good for the economy and good for the health and welfare of state residents.

The fight goes on for effective implementation and enforcement, but for now, Washington residents are justified in popping some champagne corks. The state has finally charted a clear path to a healthier climate future.

Share this post