In this episode, two Volts favorites — Princeton professor Jesse Jenkins and UC Santa Barbara professor Leah Stokes — join me discuss the Inflation Reduction Act, the somewhat miraculous last-minute agreement between Senators Joe Manchin and Chuck Schumer. It represents the tattered remains of Build Back Better, but many if not most of the climate and clean energy provisions remain intact. We discuss what's in the bill and reasons to be excited about it.

Full transcript of Volts podcast featuring Jesse Jenkins and Leah Stokes, August 3, 2022

David Roberts:

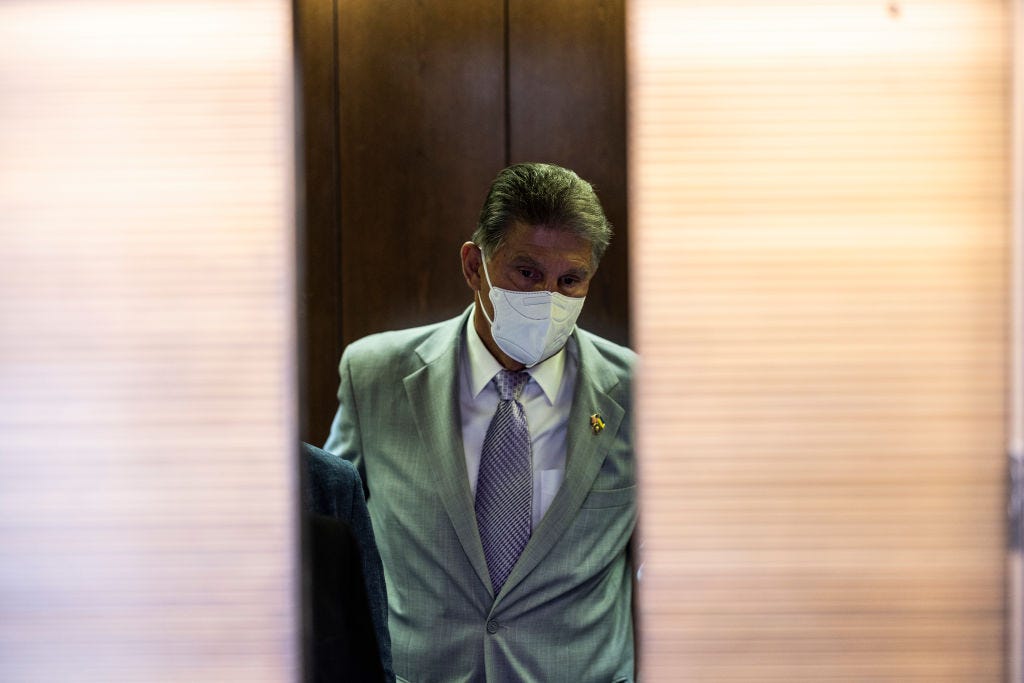

As Volts listeners are no doubt aware, Senator Joe Manchin — Our Lord and Savior, blessed be His name — seems to have found his way to an agreement with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer on a reconciliation bill. The 700 page Inflation Reduction Act would raise some taxes, reduce some drug prices, and subsidize some healthcare exchanges, but most notably, it would invest almost $370 billion into clean energy and climate change mitigation.

Make no mistake: if it passes, this bill will be a very big deal. Though it has shrunk from $550 billion to $370 billion, the original climate and energy package in the House-passed Build Back Better bill is still visible in the IRA, if you squint just right. Though the Clean Electricity Payment Program (RIP) is long gone, most of the clean energy tax credits have survived, amidst a sweeping variety of spending on everything from consumer heat-pump rebates to a green bank to money for carbon-capture and hydrogen research.

Everyone, including his fellow senators and top congressional staffers, was taken by surprise by Manchin’s pivot, so perilously late in the game. There is a bit of giddiness in the clean energy world, tempered by the hard-won awareness that nothing is certain until Joe Biden signs a piece of legislation. There are still many ways this can all go wrong.

While we wait for the final outcome, our fingernails digging into the arms of our chairs, we might as well discuss what's in the bill and what we should think about it. To do that, I've brought back two of the earliest and most popular guests on Volts: Jesse Jenkins, Princeton professor and energy modeler, and Leah Stokes, professor of political science at UC Santa Barbara.

I'm excited to talk to them about what's in the bill, what’s been taken out, what we should be worried about (and not), and what they think of the bill’s chance of passage.

So without any further ado, Jesse Jenkins and Leah Stokes, welcome back to Volts.

Jesse Jenkins:

Thank you, David. This will be a lot more fun than the podcast we would have recorded a couple of weeks ago, so I’m glad to be here.

Leah Stokes:

Yes. Thanks for having us on, David.

David Roberts:

I should emphasize up front: the bill is now out there, but it has not passed. It's got to go through the amendment process; no one's sure what Kyrsten Sinema thinks about it; no one's sure what the House “moderates” think about it. A lot of distance between us and the finish line, and we're all terrified about that.

Big picture, if it passed as written, what effect would the IRA have on US greenhouse gas emissions?

Jesse Jenkins:

A really big one.

The REPEAT project is our Princeton-led effort to model federal energy policy as it is being proposed and enacted. We've been repeatedly assessing the bill, from the introduction of the infrastructure and Build Back Better acts last year through to today.

Our estimate is that the Senate Inflation Reduction Act, as it's now called, would cut US greenhouse gas emissions on the order of 900 million tons in 2030, basically doing about two-thirds of the remaining work that needs to be done to get us from current policy trajectory down to the 50 percent reduction in emissions that we're aiming for by 2030. That's our nationally determined contribution, our pledge to the world to cut our greenhouse gas emissions down to half of peak levels.

That's all greenhouse gas emissions, excluding land use changes. We don't directly estimate the impact of the forest preservation, wildfire mitigation, and conservation measures in the bill, but our guess based on prior analysis is that that's likely to deliver on the order of another roughly 100 million tons of carbon storage and sequestration in our national forests and agricultural lands. That's additional to the 900 million tons that we're looking at in our analysis of direct emissions from energy and industrial processes across the US economy.

That'll get us to about 38 percent below 2005 levels plus or minus a couple percent. That's in the ballpark of what other teams who have been modeling the bill, including Rhodium Group and Energy Innovation, have estimated in their preliminary reports that also came out over the last few days, and around the 40 percent reduction that Senator Schumer’s staff is circulating as their estimate of the impact of the bill. All in the similar neighborhood of roughly 38-40 percent reduction in emissions.

Not quite to 50 percent, but it keeps us in the climate fight, and gives us a chance to close that gap with further action from states, local governments, corporate and institutional leaders, and individual action. All of that just gets a lot cheaper, a lot easier, and a lot more likely with this bill passing and the federal government picking up a good chunk of the tab.

David Roberts:

What is the difference between what the last intact Build Back Better version would have reduced vs. this? In other words, how much less would it reduce greenhouse gas emissions than prior to Manchin having his way with it?

Jesse Jenkins:

Our estimate was that the House-passed bill would have cut emissions by about 1.2 billion tons. We're at 900 million tons or thereabouts here, so about 75 percent of the emissions-reduction work is retained from the House bill into the Senate bill. That's a huge portion of those emissions reductions. It's much closer to the House bill than it is to nothing, which is what we were staring at a couple of weeks ago.

David Roberts:

When the first version of this bill came out, they said it was going to reduce emissions 40 percent by 2030. Then the bill kept getting cut, but they kept saying it was going to reduce 40 percent by 2030. Are there shenanigans with the baselines going on?

Leah Stokes:

That's not actually true. Schumer had put out that the previous version was going to do 45 percent. The modeling from Energy Innovation, from Jesse's REPEAT project, from Rhodium, are little bit lower than that, like 39 percent. So there is actually a downward reduction between what the Schumer team originally said the bill would do and what this version will do.

Jesse Jenkins:

We lost about one percentage point from the loss of the Clean Electricity Performance Program between the original House bill and the House-passed version; that would have cut emissions to 40-41 percent below 2005 levels in our analysis. Now we've lost 2-3 percentage points from there, down to 38 percent reduction below 2005 in the Senate Inflation Reduction Act. So a little bit of erosion as we've gone along.

But remember, this is how the legislative process works. I have to give credit to Senator Schumer's team and to Senator Wyden’s team on the Finance Committee for really being careful as they navigated this process and had to cut the budget back. The main driver of the cuts here was the desire to deliver a top-line budget that contributes to deficit reduction, as Senator Manchin was keen on.

Senator Schumer and Senator Wyden’s team and others did a very careful job – in some cases aided by the kinds of analysis that our group and Rhodium and Energy Innovation and others were doing – to focus on retaining the programs that deliver the greatest emissions reductions and to get the bill to have the biggest impact possible. You can see that borne out in the significant impact of the final bill that's showing up in all of our modeling.

Leah Stokes:

A lot of the changes were shaving the amount of money in a given program as opposed to cutting wholesale programs. There were, of course, some that fell out entirely, like the Civilian Climate Corps. E-bikes went away, sadly. There were some full-scale cuts, but a lot of the bill is still there. It's just a bit less money for each program.

David Roberts:

The original Build Back Better was an elaborate policy castle with a million things in it; it's honestly been pretty remarkable to see, as the rest of that castle falls apart, just how much the climate and energy part has more or less retained its integrity. It's stayed almost the way it was originally built, even as everything else crashes down around it.

Leah Stokes:

It’s almost like the climate movement is competent and powerful, and the left climate movement knows what they're doing, and the people who say otherwise have no idea what they’re talking about.

Jesse Jenkins:

It's worth dwelling on that point. The measures that were in the original Build Back Better Act, the immediate pocketbook-issue benefits that that bill would have delivered – child tax credit, free pre-K, child care tax credits – were things that would have made a big impact on people's lives. It's a huge shame that that bill is not what we're talking about moving through the Senate right now.

Those are the measures that you probably would have leaned into in a campaign in the midterms, that poll as the most popular measures in the bill. In the general public, there's broad but shallow support for climate action, and the kinds of benefits that we're talking about in terms of avoided climate damages truly are still far off in the future.

But there are also real near-term benefits that this bill delivers. The combination of robust effort by the climate movement to put this issue at the top of the policy agenda and keep it there throughout the sustained effort, and the ability of a lot of advocates to point at some of the tangible near-term economic benefits of this bill – on energy cost reductions, inflation reduction, manufacturing jobs, energy security – are what ultimately allowed someone like Senator Manchin to not just embrace it, but over the last week really go out and champion this bill in public and point to those kinds of issues.

David Roberts:

Whatever else you can say about the climate movement’s success trying to build any kind of public movement, one thing that's very obvious is they have succeeded in putting this at the top of the national Democratic Party's agenda, which for those of us who have been toiling away in these ditches for years, is a pretty remarkable thing in and of itself.

Jesse Jenkins:

The other thing that they've been able to do is basically make it clear that we cannot afford to fail. That is a moral argument, a climate urgency argument, and it's what I think kept it together in the end. Leah, you articulated this well in your New York Times op-ed – the costs of inaction are too great, and people were unwilling to let that happen.

Leah Stokes:

The conventional wisdom that people don't care and climate doesn't matter is just not true anymore. Like the two of you, I've been working on this issue for decades now, and I'm sure all of us see and feel how much more attention there is on the niche topics that we cover. We went through decades where nobody really cared what we did.

David Roberts:

The polling questions, the survey questions, the mechanisms we have to measure public concern about climate change, are ill-suited and old. Those questions tend to be phrased in weird anachronistic ways. We're not measuring what's changed very accurately.

Leah Stokes:

The folks who are at the cutting edge of climate polling – Matto Mildenberger, my colleague at UC Santa Barbara; the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication; George Mason – are seeing increases in concern and worry. When they do the maps where they downscale to districts and states, we see that people want their government to act. That's really consistent.

Anecdotally, I watched Stephen Colbert’s opening about climate change on his show last week and it was powerful, because every time he said “we're going to get a climate bill,” the audience lost it. They were so excited. People understand it.

David Roberts:

Back to some specifics of the bill. The Clean Electricity Payment Program got killed a while back, so what is still there to help encourage utilities and states to keep reducing electricity sector emissions?

Leah Stokes:

Jesse and I worked very actively on the Clean Electricity Payment Program; obviously, we were very devastated when it fell out. But there's still tons of stuff to clean up the electricity sector.

President Biden set a goal to hit 100 percent clean power by 2035. That was championed by Governor Inslee when he was running for president, and Evergreen Action, which I'm part of, has been key to keeping that on the agenda.

How can we make progress toward 100 percent clean power by 2035? There are long-term tax credit extensions – these are the bread-and-butter policies that we've used for years to deploy wind and solar. There were some tweaks that we wanted to make with them that didn't happen, and others that actually did, so it's a bit of a mixed bag.

Overall, it's pretty positive. For example, there will be direct pay, a grant-like program, where you don't have to have federal tax liability for municipal utilities and co-ops.

David Roberts:

In the previous version, many of the tax credits had been converted to direct pay. (That means that instead of having to invest enough to have some tax liability from which you can deduct these things, they just give you money, so you don't have to be particularly big. It's a way of broadening.) My impression is that Manchin was extremely leery about direct pay, but some people came in and persuaded him to have a little bit. How did that shake out? What is still direct pay and what isn't? And how big of a deal do you think that is?

Leah Stokes:

Municipal utilities and rural electric co-ops don't really owe the federal government money because they’re nonprofits, so they couldn't access these tax credits. That's created some big problems in the utility industry, which is that a lot of the clean electricity projects are owned by third-party companies, not by utilities, and utilities need to own this stuff in order to rate base and profit off of it.

The good news is that co-ops and munis will still have that option, and there are some other tweaks that will make it easier even for private utilities to get access to tax liability to actually build these projects. That's a key thing.

There's also $30 billion in additional investment to clean up the electricity sector, for things like a program to help states move faster on clean electricity and some programs to help retire dirty, polluting assets within the electricity system. There's great stuff that's going to put us on the path to hitting 100 percent clean power by 2035.

Jesse Jenkins:

Let me jump in on the direct pay front, because there's an important detail there on transferability.

David Roberts:

That's exactly what I was going to ask about. What the bleep is transferability? Is it a good substitute for direct pay? What does it mean, and how big of a deal is it?

Jesse Jenkins:

This is absolutely critical. Again, my commendations to the Senate Finance Committee and other people who worked out this deal.

There isn't direct pay for everything in this bill, but as Leah said, nonprofit and non-taxpaying entities do get direct pay access for the main tax credits, and that's key. They generate about 10 percent of US electricity, and they could increase that share a lot if they can now own and generate their own power rather than contract for it.

Outside of the handful of credits that did retain direct pay, taxable entities now have the ability to transfer all or part of their tax credit in any given year to another entity that has business tax liability. They do not need to be an investor or part of the project.

That is a really key change from the status quo. The only way that folks have been able to monetize the value of these credits in the past is through what's known as tax equity finance, the ability to secure investment in the project itself from a bank or financial institution or somebody else with a lot of tax appetite. They invest directly as equity partners in the project, and in exchange, they effectively get the tax credits to offset their income taxes.

They’ve been taking a substantial chunk of the value in doing that, so instead of that value going to clean energy projects, it's going to Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase, our favorite friends over there on Wall Street. Somewhere between 15 and 25 percent of that value may be going to those tax equity partners. That's just bad public policy. It's fiscally irresponsible, and it delivers a lot less benefit than it could with direct pay.

Transferability is somewhere in between, because you still need to transfer your tax credit to another entity with tax liability. But it's now much easier to do that, and that opens up the market to anybody with corporate tax liability instead of somebody who wants to go through all the due diligence and complicated deal structuring and everything that's required to enter into a tax equity deal with a wind or solar or other clean energy project.

Now what we're likely to see is a much more liquid market for transferring or selling these credits to other businesses with tax appetite. The transaction cost of that is likely to be a lot lower – in the 3 percent range once things really get off the ground, maybe 10 percent initially. We took a very conservative approach in our modeling and assumed 5 percent transaction cost and 5 percent profit margin for the transfer entity, because you don't want to pay $100 million for $100 million in credits, you don’t get anything out of that, so they maybe will pay $95 million for $100 million in credits. But it's going to lead to a lot easier time monetizing those credits.

As importantly as the lower transaction cost, it also removes the total cap on the volume of tax equity available. This was going to be the real killer if direct pay was entirely removed, because there's just not enough tax appetite in those big banks and others that are willing to engage in tax equity deals to monetize all the credits in the bill. So this was key. The transferability ability for the main tax credits is going to make sure that their full value can be captured and that they're not artificially capped by the willingness of tax equity partners to get involved in these projects.

David Roberts:

Climate policy discussions are constantly going back and forth about carbon tax vs. this vs. that, what's the right mechanism – but if you look at performance, it's these tax credits chugging along in the background that have always basically been the US’s biggest and most efficacious clean energy policy. They don't get celebrated that much, but they really are the workhorses, and they’re getting expanded and extended in here. That alone is a very big deal.

Jesse Jenkins:

We have never had 10 years of consistent federal energy policy and support for these kinds of things. We have no production tax credit for wind at the moment (it's fully expired) and a 60 percent value for the investment tax credit (we lost 40 percent of that and it’s supposed to go away next year), and we're now going back to the full value of these credits. It's about $26 a megawatt hour for a production tax credit in today's dollars, and 30 percent investment tax credit. There are bonuses that can increase that further if you invest in energy communities and if you use domestic content, so those are industrial just transition policies that further increase the value of those credits. And they're on the books for at least 10 years.

David Roberts:

That's so huge. They've been variable and unpredictable in the past, and wind development in the US fluctuates with the credit, so 10 years of predictability is such a long open runway.

Let's untangle the electric vehicle tax credits. Manchin objected to the provision that union-built EVs got extra – that's gone. But he's put some new restrictions on it in terms of means testing and domestic content. Talk us through how the EV tax credits shook out, and once again, whether that should be on our stress list or not.

Jesse Jenkins:

I'm not personally stressed about this one. Beyond being a little bit more challenging to comply with, this is actually good industrial policy and can have strong benefits for the political durability of the energy transition. What Senator Manchin essentially insisted on was that we were not going to send tax credits to Chinese battery manufacturers or critical minerals producers, that they were going to go to US or North American trade partners.

David Roberts:

But those don't really exist, do they? You don't want to send money to China, but they're doing all the critical minerals and most of the batteries. Where are we now on the existence of a North American supply chain?

Jesse Jenkins:

Here's what the bill does. It restores the $7,500 electric vehicle tax credit for personal vehicle sales. However, it is now broken into two pieces, each worth $3,750, and to qualify for each one you have to meet certain content requirements.

The first piece is about critical minerals. There's an increasing share of the value of critical minerals that have to be extracted or processed in a country that has a free trade deal with the US or is recycled in North America. And a percentage of the value of the battery components have to be manufactured or assembled in North America. That starts out at 40 percent for minerals and 50 percent for the battery component value; it goes up eventually to 80 percent for minerals and 100 percent for the batteries.

It's a pretty aggressive ramp. In the near term, there may be some challenges complying with that. But it's worth emphasizing – and this is something Manchin himself kept saying, which is true – that the EV supply chain is constrained right now, anyway. In the meantime, it helps make those purchases more affordable for the models that do manage to comply with the standards and claim those credits.

Right now there's a cap on the number of vehicles that each manufacturer can sell before that $7,500 tax credit goes away. Tesla's blown through that cap, Ford has gone through it, GM and Hyundai and Toyota are all nearing it. So compared to nothing, which is where we were headed, this is a really helpful policy that will make EV purchasing more affordable for low- and middle-income families, and, as importantly, will provide a huge incentive to build out the US and North American supply chain.

David Roberts:

To get a domestic supply chain for a whole industry, starting from almost nothing, you need a really big carrot. Is this big enough?

Leah Stokes:

What we're talking about here is just one piece of the manufacturing investments in the bill. There's about $60 billion of clean energy manufacturing components to this bill.

That is actually what we were missing two weeks ago, when we were living in the land of executive action only. How exactly were we going to build the clean energy industry of the future here in the United States with well-paying, hopefully union jobs without carrots? If we just took an executive action approach with sticks, we might still be deploying clean technology, but it wouldn't be made here.

It's important to be building those industries, not just from a jobs and economic perspective, but also from a political perspective. Because if we want to win next time, and we want to win more easily, and we want to flip some Republicans to start actually caring about the climate crisis, we need to have employers in all the states working on the clean energy industries of the future and employing people.

David Roberts:

Do we have a good sense of where an EV supply chain would be located in the US once it starts getting built?

Jesse Jenkins:

We're seeing those investment announcements all the time, from all the major automakers and battery manufacturers, and basically it's mirroring where the current automotive industry is mostly concentrated – Michigan, the Great Lakes region, and the Southeast. But there's Rivian opening up in Georgia, you've got manufacturing moving to Texas for Tesla, so there’s quite a range of places.

When you change the technology base, you can also change the supply chain up. I imagine it will shift a bit from where things are historically, but a lot of this is going to go into the same regions right now that are producing the bulk of the vehicles and components for those vehicles in the industry.

Leah Stokes:

There's going to be other manufacturing, too. We're not just talking about EVs. This bill has manufacturing incentives for solar; for batteries that go into other things, like the grid; we've got heat pumps through the Defense Production Act. There's an enormous amount here to build the industries that we need.

Let's also remember the solar commerce issue that we dealt with this spring, where one company in California said “we should be doing solar panels here in the United States instead of importing them, there are these companies that are circumventing the tariffs with China” and the whole industry basically shut down. Thankfully, President Biden had already declared a climate emergency so that he could invoke the Tariff Act and say “no new tariffs for two years,” and that was critical to reopen the imports of solar.

Some of the domestic companies – which are a very small part of the solar industry, but still – were upset and wondered why he did that. Well, this is the answer. If we want to build the domestic industries here in the United States, we can't really do that with regulation, we've got to do it with investments. That is what is going to be so transformative, alongside many other things with this bill.

I recently saw data that there's been $180 billion in clean vehicle manufacturing invested in the last few years. Companies are going to match this money. It's not just the government acting; when we invest, companies invest too.

Jesse Jenkins:

We're all unfortunately old enough and have the scars to remember the failure of our last federal effort to pass climate policy in 2009. There was a lot of rhetoric at that time about green jobs and the economic benefits of that policy, but in 2009, the policy was mostly sticks and not a lot of carrots. It was a carbon pricing bill to cap emissions and price carbon dioxide. The assumption was that that would drive some investment in clean jobs, and that was what the rhetoric was centered around.

This bill is actually focused on making sure those good clean energy jobs deliver for real, providing tangible economic benefits for communities all over the country. It does that in a ton of different ways. We've talked about the EV domestic requirements; there's also a bonus in the solar and wind and clean electricity tax credit for using domestic content. It goes up by 10 percentage points for the ITC, so you can get a 40 percent investment tax credit if all the steel, aluminum, and concrete comes from the US and the rest of the manufactured content is majority produced in the US.

Erin Mayfield at Dartmouth University and I put together a paper last year looking at the extra cost of producing solar and wind in the United States, and we found that that was quite a small incremental cost, a couple of percentage points increase in the final cost of installed wind or solar projects. So that 10 percent credit is enough to cover that gap.

But that's not all. Again, we’re not just doing it on the demand-pull side. We're also providing money on the supply side with a new advanced manufacturing tax credit, which was championed by Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock from Georgia originally around solar component manufacturing, but now also includes wind component manufacturing and offshore wind ships – these special ships that cranes that can go out at sea and install the giant turbines – that we need to build out the offshore wind industry.

What was added in the Senate version, in negotiations with Senator Manchin, are production tax credits for the supply and processing of critical minerals. There's a huge list of the periodic table that qualifies for a 10 percent production tax credit on the manufacturing and processing side.

For lithium ion or other battery cells, modules, and electrode active materials – that's the minerals that go into the electrodes in the battery – there's a pretty hefty credit, too. It's worth about 30 percent of the cost of a battery cell or battery pack, and again, about 10 percent of the value of the minerals.

We're throwing real money at this. I think it's going to be one of the things that we look back in 10 years and, beyond celebrating the emissions reductions progress that's been made, we're really going to recognize this bill as totally changing the direction for the economy, for our clean energy transition, and for the politics of sustaining that transition over time.

David Roberts:

Will the range of investments in domestic manufacturing that you're talking about hit the streets quickly enough to make a material difference in the 2024 election? What's the timeline on these?

Leah Stokes:

There are lots of different parts to the bill, and it's possible that other things are going to hit faster. We haven't talked about the consumer-facing tax credits. There's a new tax credit to help people get a heat pump, to help upgrade their breaker boxes if they want to put in EV charging and they need a higher panel at their house – those are things that everyday Americans are going to be able to access.

There's a whole other program as well that mirrors that for low- and moderate-income folks, which is a grant or rebate program. It doesn't require federal tax liability. So those might be some of the things that really matter. They start next year.

Offshore wind is an industry that is pretty likely to be unionized, and that's exciting to have higher union density in the clean energy economy, because that's something we've struggled with. We've had higher union density in fossil fuels and dirty energy than in clean, and that's made it harder to have the unions come along with the clean energy investments we need and with climate action. If we can get offshore wind to be a unionized industry and made in America, that will be huge in terms of changing some of the political dynamics going forward.

Jesse Jenkins:

Every tax credit is tied to prevailing wage now.

David Roberts:

The consumer stuff is fast, but how fast is the manufacturing stuff? Is it fast enough that we'll see substantial numbers of jobs soon?

Jesse Jenkins:

We're talking about accelerating a transition that's already underway. There's $180 billion of investment going into clean vehicles manufacturing; there are jobs and factories and ribbon cuttings all over the country that are part of this transition that will be accelerated by the bill.

You're not likely to be able to say that 2024 is going to see a huge surge of increased investment from the bill, although it will be higher than it would otherwise. But a politician can pretty credibly and easily point to the kinds of jobs that are materializing in this transition, rally around a bill that is going to accelerate that, and bring it home in the form of domestic manufacturing, investment in energy communities, and prevailing-wage, well-paying jobs all over the country.

I think that's how this bill is going to manifest in the near term. In the longer term, real constituencies are going to see their economic future and their economic prospects in the continuation of that transition, which is key for sustaining and accelerating our progress over time.

David Roberts:

Let's do a quick turn through all the many ways that consumers are going to be able to access some of this money.

Leah Stokes:

I've got to give a shout out to Rewiring America, which I also work with. We worked pretty tirelessly to try to get a bunch of these things across the finish line. Really grateful for their leadership on this one.

There is, of course, the EV tax credit, that's important. It costs about $1 a gallon to run an EV, compared to $4-6 a gallon to run a gas-powered car, so it's going to be big if people can get an EV.

In addition, people can get solar panels. There's a tax credit called a 25D; they tried to get that to be direct pay, but tragically, that didn't happen. There's also a bunch of solar panel stuff in the green bank, what's called the clean energy accelerator – that's a $27 billion program that's going to help deploy projects in communities. That could be more consumer-facing than we might think, because it could, for example, help do community solar.

My personal favorite, and the stuff I spent a lot of time on, was heat pumps. This is an amazing technology that can both heat and cool your home efficiently without using fossil fuels. That's great for your health, it's also great for the planet, and it helps you save money.

A program that Senator Heinrich championed – originally called ZEHA, now called HEEHRA – is for low- and moderate-income people to get access to heat pumps, heat pump hot water heaters, even an induction stove, and it will cover a huge amount of the technology. It's up to $8,000 for a heat pump. There's $4.5 billion for this program, and I think we're going to run through that money relatively quickly and have to get more. I think it's going to be really popular.

For the wealthier Americans who don't need a rebate because they owe the federal government taxes each year, there is something called 25C, which is a tax credit for now. It's going to be for heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, and breaker boxes, and it's going to pay for up to 30 percent of a heat pump. It's super exciting, it's going to make it way more affordable for people to get heat pumps.

Hopefully we'll start seeing heat pump manufacturers move to the United States and start making this stuff here, which is something that Rewiring America has been working an enormous amount on.

To summarize: If an American household adopts the technologies that this bill is going to make more affordable – getting an EV, putting solar on your roof, getting a heat pump, getting a heat pump hot water heater, etc – you can save $1,800 a year on your energy bills going forward, every single year.

There are places where people heat their homes on oil and delivered fuels like propane. It's really expensive if you're living in Maine or the Northeast or the Midwest, and right now with oil prices where they are, if those households take advantage of these tax credits, we're talking about $3,000 or more a year in savings.

David Roberts:

It's a big deal for anybody, but it's a bigger deal for low-income people who legendarily spend a larger portion of their income on energy. Also, the price of oil and natural gas and gasoline are constantly fluctuating completely outside our control, and the price of electricity tends to be stable over time. So it's not just lower costs for low-income people, it's more predictable, steady costs.

People underestimate what a big deal that is, being able to predict month to month, year to year, what the costs will be and not being on the ass end of these global markets where gasoline could go up to $5 a gallon and it's completely out of your control. Electrification is a beautiful thing.

Leah Stokes:

I totally agree. That volatility issue is something that Rewiring America talks about all the time. When we call it the Inflation Reduction Act, 41 percent of inflation is being driven by fossil fuels directly, to say nothing of the indirect ways fossil fuels are driving up goods and services, to say nothing of the climate chaos and all these impacts from weather and how much that's driving up inflation too. Fossil fuels are at the heart of this inflation crisis, and getting people off fossil fuels is really going to help them save money,

David Roberts:

There's this provision now that basically says that if you're going to lease federal land for solar and wind, you also have to at the same time lease X amount of land for oil and gas development. Where the hell did that come from? Have you ever heard of anything like that before? And to return to our theme, how worried should we be about it?

Jesse Jenkins:

This came directly from Senator Manchin’s demands and concern that in a moment when oil and gas prices are driving up consumer costs and we're going to Saudi Arabia to beg them to produce more oil, he thought it was ludicrous that we would not be producing more oil in the United States. That's his point of view, and this bill had to have something in there that he could point to to say this was going to support all American energy production, not just renewables.

David Roberts:

I can even see mandating oil and gas leasing, but to tie the amounts together –

Jesse Jenkins:

It does both, unfortunately (or however you want to take it, I'll try not to be too value-laden). There are two provisions, the so-called “poison pills,” depending on how you're looking at it, that he added in.

One is that it does require five different lease areas that were previously offered and withdrawn due to environmental concern to be reinstated, and that the National Environmental Policy Act review is approved, which is basically saying that these five lease sales all are going to move forward now. Of course, folks in those communities and environmental groups that have been fighting those leases for years are furious about that, overturning the legal process and putting those back into play.

The measure that you mentioned is basically designed to tie the president's hands and say “if you want to develop renewable energy on public lands or waters, you cannot ban the lease of fossil fuels on federal lands and waters.” It's trying to codify an all-of-the-above approach to federal lands and waters that reflects Manchin’s priority and perspective.

It also reflects the business-as-usual course, at least for the near term, because the federal government is leasing new oil and gas leases now. After President Biden paused those leases in the beginning of his presidency, the courts overruled that effort, and the secretary of interior is issuing new leases. There is nothing to bind a future Republican president against offering these leases as well. It's too bad that the program isn't reciprocal, that it doesn't say “if you want to do oil and gas leases, you also have to do wind and solar.”

There are ways that presidents who want to can finesse and manage this. Your perspective on this is going to vary tremendously depending on your stakes in the issue. If you live near one of these lease areas, you're going to have a very different perspective than I or others might have on it.

If we're just looking at the carbon dioxide emissions, this really is not a killer. How much of this is additional vs. business as usual is hard to parse out, but it's certainly not all additional; any production resulting from additional leasing on federal lands isn't leading one-for-one to additional consumption. It's displacing production on non-federal lands and overseas and in other parts of the world in the oil and gas market. Our estimate, which aligns with Energy Innovation’s as well, is that for domestic emissions this is no more than 50 million tons of emissions per year in 2030, and it's probably less than that.

David Roberts:

How confident are you in that number? People who are exercised about this poison pill also say that these models tend to underestimate the mid- and long-term effects of leasing. How confident are we that we know the carbon impact of leasing policy?

Jesse Jenkins:

I think we know the general magnitude of it. No one can predict the future with accuracy, and it is true that the leasing impacts are most prevalent in the longer term, because any lease offering next year takes some time to develop and then some time to come online. There might be a slightly larger impact in 2035.

But we have to keep in mind the scale of this. We're talking about 900 million tons of emissions reductions from the bill overall, and somewhere on the order of 50 million tons that this provision will cost us. Maybe it's 5 percent of the impact of the entire bill. That sucks, but is certainly not a reason to be concerned about the overall emissions impact of this legislation.

David Roberts:

If you want to be somewhat cynical about it, if you need something for Manchin to have to wave around to show that he got his pound of flesh, a relatively small impact change like this is better than some other alternatives you could think of.

Leah Stokes:

It's not like this is what we would have written. It's not a good provision. It's not good for the communities who live by these places. It's not good for the planet. It's bad.

But we have to contextualize it. A lot of the movement has been built around supply-side fights, meaning stopping fossil fuel development; that's valuable, and it's been powerful. But there is a complementary theory of change here, which is crushing demand for fossil fuels. How do we do that? We get people in EVs, we get them heat pumps, we build solar manufacturing here and we put solar on all the roofs. That is what this bill is going to do, and that's going to crush demand.

When we deploy these clean energy technologies here at scale, we're going to reduce the costs. That doesn't just matter for the US – it's going to spill across borders. It's going to reduce the costs everywhere around the world.

Jesse Jenkins:

If I were an environmental justice or climate justice frontline community, I'd be most pissed about the overriding of the previous lease withdrawals and the fact that these five specific leases are moving forward. That's just not good due process. That's not how it should work, the legislature coming in and saying “no, these specific ones, they're moving.”

The other leases should go through due process. We have all the same tools we have to try to protect communities from the impacts of any potential development on these leases. The requirements are to offer lease acreage, not necessarily for those leases to be developed. We already have oil and gas companies saying that they're expecting peak demand for oil in the not-so-distant future, the neighborhood of 2030. We're going to try to crush this on the demand side, and this is going to accelerate that effort tremendously. What Europe is doing to get away from Russian fossil fuels now is going to accelerate that transition. We can win here, and we can avoid this leading to a large amount of new oil or gas production on net.

Look around at the politics of the moment today, with gas prices soaring, President Biden running around to Venezuela and Saudi Arabia begging them to produce more oil, releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. This is the kind of stuff that happens when energy prices spike, and they will spike if we try to drive this too much on the supply side, by constraining oil and gas supply, and not enough on the demand side, driving demand reductions in oil and gas.

This bill certainly is going to do a heck of a lot more on the demand side than on the supply side, but that’s going to enable us to make that transition much faster, and it may actually even make those supply-side efforts easier in the future because there's going to be less demand for new oil and gas development once we do this.

David Roberts:

As Kingsmill Bond shared with Volts listeners several months ago, there's a very big difference between an industry that is slowly growing and an industry that isn't growing anymore. Even if the number difference isn't that big, the business, psychological, sociological difference is huge.

Leah Stokes:

Right now, a lot of these fossil fuel companies are making crazy money, and they're just giving it back to investors in massive dividends. They're not holding on to cash so that they can develop a bunch of new fossil fuel extraction sites. They're saying “I don't know how good our business is going, let's give this back to our shareholders so they hold on to our stock so our stock doesn't tank.” They're not saying “I really want to build a new offshore platform in the Gulf.”

Just because leases are offered does not mean they are purchased or even developed. There is a long process between a lease being offered and it being developed, and we can do a lot of things along the way to stop these projects.

I did a little bit of the math. If there’s 60 million that has to be offered offshore according to this bill, the 10-year average between 2010 and 2019 was 80 million. So it's a little bit less than the historic average. For onshore, you have to offer 2 million acres, and historically, that same period, it was 5 million that was offered. So again, it's lower.

These are not good numbers, but they're lower than the 10-year average before the pandemic. And we've seen some folks who are real experts in this topic saying something like 1-3 percent of lease acreage that's offered is actually leased. I don't think that even means it's developed, that just means it's leased.

David Roberts:

This oil and gas leasing part is fairly seen as a blow to frontline communities. However, I personally have found it remarkable how much environmental justice stuff was in the original bill, and doubly and triply remarkable how much of it survived. As far as I know, that portion is more or less intact from the very original. Talk us through what's in there for environmental justice.

Leah Stokes:

There's about $60 billion of environmental justice investments in this package. The Equitable & Just National Climate Platform, which is a coalition of EJ groups and big green groups, worked really hard to make sure that EJ voices were represented in the process. They had their priorities, and a lot of those priorities are in there.

David Roberts:

Kudos to them. They’ve not traditionally been a big player in national climate discussions, and in the last five years, they have organized and put themselves in this process and achieved an amazing amount of environmental justice stuff in there that seems bizarrely uncontroversial.

Leah Stokes:

That's a big accomplishment, and it's being overshadowed by the dark, crappy stuff that was put in the bill. Some people are saying “movements weren't behind this” or something like that. I don't agree with that at all. I was in coalitions with groups for the past 18 months – we met every week, we had open processes, we had environmental justice advocates participating, and the Equitable & Just National Climate Platform is a process to do that. I'm not saying everything is perfect, or everything that we wanted to happen happened, but this is a lot better than we've done in the past, and $60 billion is a lot of money.

Senator Markey has been out in front working on these issues. There's $3 billion to clean up ports, which are a big source of pollution in communities of color. There's another $3 billion for community block grants to help environmental justice communities set their own priorities about what they want to be doing. That's a great win.

Then, as we mentioned, there’s something called the Clean Energy Accelerator. Senator Markey worked on this. It's like a green bank. There have been people working on this for a long time, and it's $27 billion. So that was pretty much intact.

David Roberts:

All meant to leverage private capital, right? It’s going to leverage a lot more than that in private capital.

Leah Stokes:

Yes, and $15 billion of the $27 billion, so about 55 percent, is for disadvantaged communities. The lion's share of the accelerator is going toward environmental justice priorities.

For example, the program that I worked on, that Senator Heinrich led, about these low- and moderate-income rebate programs to help folks get a heat pump – that's a transformative program. There's $4.5 billion dollars for that. I would always love more money, we need to do a lot, but this is actually really good news. These were the priorities of many groups in the environmental justice movement, and I'm thrilled to see them in the text.

In addition, for all the flaws in the infrastructure bill – there's a lot of fossil fuels in there – there are important environmental justice priorities too, like dealing with lead pipes, and also having electric school buses.

I know there are some groups who are upset, and I get it. This is not the bill that I would have written. I worked on the bill very actively, and I worked to make it as good as possible, and I worked with environmental justice groups – not all of them, not everyone, but I did. A lot of people in the environmental movement did that in good faith and tried really hard.

We're dealing with the reality of 50 votes in the Senate, the last one of which is Senator Manchin, who we all know has made $5 million off of coal. It's not the perfect solution here, but I feel like we got a lot of good stuff, and we can't miss that.

David Roberts:

Compare this to the environmental justice community's involvement and results the last time we did this, in 2009 with the Waxman-Markey bill. It’s night and day. They were involved early on this time, they were at the table, they organized, they stood up for themselves incredibly well. It's all what your baseline is, what you're measuring against. To me, relative to 10 or even five years ago, clearly the EJ community has secured itself a seat at this table. They're not getting overlooked anymore. They're a player.

Leah Stokes:

They didn’t get everything they wanted. I didn't get everything I wanted, big green groups didn't get everything they wanted, nobody did. The Justice40 was about trying to get 40 percent of the investments – we're not quite at that number, but we still are pretty solid here. Then it became 40 percent of the benefits, which was not what EJ groups wanted it to be.

At the end of the day, this package is going to deliver a lot of good for low-income Americans, for communities of color, for frontline communities. There will be some bad; we've got to fight that bad as a community together and to try to make sure that we deliver justice, because that is what matters. I know it's not perfect, but we've got to let great be good and not let perfect be the enemy of the great.

David Roberts:

A couple more details I want to hit. Tell me about the history of the methane fee. How big of a deal is it?

Jesse Jenkins:

The methane fee has been in the bill from the beginning, in the House Build Back Better Act. The idea is to put a fee on upstream emissions of methane pollution in the oil and gas supply chain. That includes leaking from oil and gas wells, from pipelines, and other stages along the way.

Methane is a very potent greenhouse gas in the short run, so it's an important one to cut as much as possible, and it's something that we can make very near-term, very economic progress on. It's a key piece of the puzzle to get us to our 2030 goal of cutting emissions to half of our peak levels.

The methane fee basically provides a financial penalty – it's our first foray into carbon pricing, or methane pricing, I guess – that would penalize producers of oil and gas that emit above a very low threshold level in a variety of different covered processes throughout the supply chain: wells, compressor stations, pipelines, storage tanks, things like that. It also provides $1.5 billion for grants to help companies actually monitor and reduce emissions.

This works hand in hand with a proposed EPA regulation on methane emissions that the Biden administration has put forward and is moving its way through the rulemaking process. New in the Senate version, since that rule was introduced after the House bill came out, it says that if a company complies with the EPA regulations, they're not subject to the methane fee. Those will have to be calibrated to be roughly equivalent, but it basically says: meet the rules, we'll give you some money and you don't have to pay anything; don't meet the rules, you're going to start paying a bunch of money. That's going to provide a very strong incentive to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and methane pollution across the oil and gas supply chain.

That's another thing to keep in mind when we're talking about the emissions impacts of any federal leasing – those emissions are going to go down with this measure. There's also a provision that raises the lease rates and rental rates for federal oil and gas production. That's good news for funding for communities that are impacted by those developments, but it also is a further disincentive for public development of federal lands that mitigates some of the impact of the leasing provisions.

All in all, there's a lot that targets the oil and gas sector, that tries to encourage reductions in emissions, that requires them to pay a fair share for development of public resources.

Leah Stokes:

People are missing the impact of the royalty rate increases. On the one hand, more leasing, you have to do it, that’s terrible. But hey, if you buy those leases, you need to pay more money to the federal government. That's going to make it less profitable. If oil prices fall globally, which hopefully they will, that's going to eat into the profits and it's going to make it more risky for those developments.

Senator Carper gets credit on the methane fee. He worked a lot directly with Senator Manchin and championed this for a long time.

Jesse Jenkins:

There are a range of views across the oil and gas industry about methane emissions. The big oil companies all see this as an area that they can tackle successfully; it's part of their ESG commitments. It's really the smaller oil and gas producers, the wildcatters and others that just want to get in and make a quick buck, that are concerned about this.

Trade groups that represent developers overall had been opposed to it, so this is a win to beat back the fossil fuel industry and get this methane fee over the finish line.

Leah Stokes:

People who say there are no sticks in this bill are forgetting the methane fee. They're also forgetting that we still have a president named Biden, who will be able to do regulations, which are sticks, when this bill finally gets signed into law.

Jesse Jenkins:

That's a good segue to another point. There was a reaction, and it's a logical one, when it looked like the bill was going to fall apart: “okay, fine, forget it, we're just going to go to ‘executive beast mode,’” was the quote from Senator Whitehouse. It's important to recognize that by making all of these clean energy and emissions-reduction solutions cheaper, that actually makes it easier for a president and the federal agencies to propose more aggressive regulations.

David Roberts:

If you dump a bunch of money into carbon capture tax credits, which this bill does, you stand up the carbon capture industry, you help develop carbon capture technology – voila, carbon capture becomes a viable, best emission reduction scenario for EPA’s purpose. EPA can then come and say “hey look, we spent a bunch of money, we stood up CCS, and now it's available, so you have to use it.”

Jesse Jenkins:

That’s true as well for the fuel economy and tailpipe emission standards for light, medium, and heavy duty vehicles, which the administration is working on now. All of those will be more ambitious with the passage of this bill, not less.

The converse was actually true, that we weren't going to see “executive beast mode”; we were going to see more cautious regulations, because especially given the Supreme Court, you can't propose a regulation that has a really narrow cost-benefit analysis, a lot of costs and burdensome compliance for the industry, or you're going to get huge legal fights and you're going to likely wind up and lose at the Supreme Court.

The fact that we now have all these carrots in there as well makes it easier for the administration to pick up a bigger stick, and for people to not be so afraid of that stick because they can meet it. They can clear the bar.

David Roberts:

This will not replace Joe Biden's executive actions; it will strengthen his hand as he takes them. I get why the Center for Biological Diversity has to put out these Joe-Biden-could-do-anything-he-wants papers, but we all know Joe Biden and his administration. He was never going to go into beast mode. Beast mode is not in his repertoire.

Leah Stokes:

I don't know if I agree, actually. A lot of people have used the lack of splashiness and aggression as a sign that they don't care, they're not going to do beast mode. Personally, I think it's been a sign that they really want to get this package over the finish line. They don't want to spook Joe Manchin; they know it's hard to get him to stay in one direction for long. And the last thing we needed to do was use weaker tools at the expense of a transformative package.

I know people who work in the White House. They are as aggressive on climate change as anybody. We have smart folks who care and have lots of ideas, and they've been waiting for the right time. Until last week, everybody was like “they're stupid, they messed it up, blah blah blah” – well, now maybe they're looking pretty smart.

I just think it's a little more complicated than “they don't care” or “they're not going to do aggressive stuff.”

David Roberts:

We did a pretty good job here covering the substance of the bill, even though there's tons in there that wasn’t mentioned: there are tax credits for wind, solar, geothermal, hydrogen, nuclear; the green bank; the consumer tax credits and consumer rebates; the methane fee. Are there any substantive legislative pieces of this that we didn't cover that you want to give a shout out to?

Jesse Jenkins:

We didn't talk much about the things that some people are a little bit more ambivalent about, but I think are actually pretty critical.

Wind and solar and batteries and EVs are cheap today because we invested public resources in their early-market deployment for a decade-plus. We drove down the cost by 90 percent for batteries and solar and by about two-thirds for wind. We need to do the same thing this decade for a range of technologies that we need to be ready for primetime in the 2030s and 2040s if we want to blow past that 50 percent reduction on our way to net zero.

So the bill also helps do that, along with big investments in demonstrations in the infrastructure law. It provides the first early-market policy support for clean hydrogen production, for carbon capture and storage, for advanced nuclear, and a range of other technologies, like sustainable aviation fuel, that are in a more nascent stage today and are really not going to find a beachhead in the market without this kind of policy support.

With that wind at their backs, we can be confident – not that all of those shots on goal will succeed, but that enough of them will that we will have the complete energy team that we need to win the game in the 2030s and 2040s. Again, it's one of those pivotal moments that we're going to look back on in 10 years and say wow, these industries that wouldn't have otherwise existed are now real, primetime, mature industries that can help drive down emissions.

David Roberts:

I look back at the amount that Obama's stimulus bill spent on energy, which at the time seemed huge, but is tiny relative to the amount of money we're talking about now.

Leah Stokes:

It’s four times bigger.

David Roberts:

That bill played a big role in exploding the US solar and wind industries; it basically created those out of nothing with a much smaller amount of money. Ten years from now, the amount of money we're talking about investing is going to have transformative effects, and we have a track record showing that these kinds of investments can stand up industries and get them on their own two feet.

Leah Stokes:

I would be remiss if we didn't talk about another Volts favorite in this package: $3 billion for USPS to purchase zero emissions vehicles. There's actually $9 billion total for the US federal government to do procurement of clean energy technologies – heat pumps, clean cars, solar panels, you name it.

If folks want to see a pretty comprehensive explainer, they can go to EvergreenAction.com and there is a very long – but not as long as the bill – explainer that breaks down a lot of programs.

We've been going on here for quite a long time, and we still have not touched on all the things that are in the bill. This is a vast forest of clean energy and climate investments. There are some trees in the forest that are sick and diseased and not great, like the leasing stuff, but they're just a tree, and there's a vast forest of lots of other things that are in the package.

David Roberts:

All in the context of a 50-vote Senate majority, a president under siege by inflation – if this thing squeaks through in this environment, it will be an m-effing miracle, relative to what we reasonably could have expected.

Leah Stokes:

I've got to put a plug in for Call4Climate.com. All you have to do is dial and it will patch you through directly to your senators and representatives. Takes two minutes. If you've got friends in Arizona and West Virginia, ask them to go to Call4Climate.com today, tomorrow, the day after. You can even look in your phone for Arizona and West Virginia area codes in case you forget who your friends are (this was an idea from Sam Calisch at Rewiring America).

These offices don't actually get a lot of phone calls; your phone call matters. We've got to get this bill over the finish line. That's something that everyone can do right now.

David Roberts:

Is there anything else to say about the concrete politics of getting this passed? Do either of you have any non-hand-wavy speculation about its prospects? What do you think is going to happen next?

Jesse Jenkins:

We're over the hardest part – convincing a very moderate senator from West Virginia, where Trump won by something like 60 points, to embrace this bill and go on TV and champion it and meet with Kyrsten Sinema this week and sell the bill to her.

But we're not done yet. From here, the parliamentarian has to review the bill, to make sure that it meets all of the arcane, totally arbitrary rules of the US Senate that allow them to pass only budget and spending and revenue bills. The Republicans have been reviewing the text since it came out and they're going to throw some challenges her way. Schumer's team are going to argue through it, and hopefully we'll find the results of that in the next 24 hours.

Then it's going to go to the floor for a series of amendments developed by the Republicans to be as politically uncomfortable as possible for Democrats to vote no on. They will all walk down to the floor arm in arm and vote no on every single one for 12 hours or however long they allow. And then, hopefully, this bill passes the Senate on Friday.

Leah Stokes:

Friday or Saturday, depending on how long those votes go for.

David Roberts:

But we can promise listeners at least this is the last week of hair loss and fingernail chewing.

Leah Stokes:

There's the House, my dear. There's a second chamber.

David Roberts:

Too many chambers. I don't know why we need this many. There's been some discussion about whether a group of moderates in the House are going to kick up a fuss about the SALT deduction or whatever. Do we have any signals or knowledge of whether that's going to happen?

Jesse Jenkins:

A handful of Democrats are going to torpedo the only chance at passing substantive Democratic policy victories before a narrow midterm election over a tax cut that benefits upper middle class homeowners in a handful of states? I mean, they better as hell not. I don't think they're that insane.

Leah Stokes:

We have to remember that we've got Nancy Pelosi here. This is someone who has actually passed two climate bills: Waxman-Markey and the now dead Build Back Better. I have a lot of faith in her and her ability to deliver.

I'm feeling pretty good about the Progressive Caucus. They understand the stakes here and how important this is. And I'm hopeful that those moderate Dems will get in line and recognize that this is the most important bill that they can pass. Fingers crossed that Nancy Pelosi pulls another one out of the hat.

Jesse Jenkins:

We all got to spend a week staring at the abyss of utter defeat, going through the stages of grief that we all went through. And we're not alone; it wasn't just climate advocates that went through that. It was everybody looking at the politics of a totally failed Democratic policy agenda at the beginning of midterm campaign season.

That puts a lot of fear in a lot of people. I think and hope that they're going to respect the fact that this is the shape of the bill and you cannot mess with it, and that it is going to pass as soon as possible. Our brief wandering through the wilderness there is going to help everybody buckle down and get this done so we can all move on to the next thing in our lives, for godsakes.

David Roberts:

Pretty soon we’re not going to have to care what Joe Manchin thinks. For this last week, as Leah says, Call4Climate.com. If you want to pester your senators to not screw this up at the last minute, now's the time for the final mobilization. Get this thing limped across the finish line at the last conceivable minute.

Leah Stokes:

It's a miracle. People need to remember the stakes here. We saw what failure looked like in the past two weeks. It was devastating. I really did hold my children and sob. It was terrifying to think about what kind of planet we would be leaving ourselves, let alone our children, let alone our grandchildren. We can't forget that feeling. That's the stakes here. Failure is not an option.

Jesse Jenkins:

It seems like a miracle, but it didn't come out of nowhere. It came down to people. People can make a difference here, people who refused to let it end that way, who said “nope, that's not how it's going to go down in history” and got back at it and put as much pressure as possible on Joe Manchin to get back to it.

Ultimately that worked, and I don't know that we all had much hope that it would. But we all knew you had to do everything you could and play it out to the last minute, or you wouldn't be able to look at your grandkids or your kids and say “we did everything we could.” We did everything we could this time, and we are all much better for it.

For anybody who's feeling defeated, or cynical about the ability of people to make a difference when they work hard at something, this is the antidote to that, because countless people doubled down at the last minute, refused to let it go down as a loss, and brought it back from the edge of defeat to get it across the finish line.

So keep at it. Keep putting the pressure on until this lands on the president's desk and we can all celebrate a huge climate win.

David Roberts:

Thank you both for coming back on. Thank you, obviously, for your years and years of labor.

Jesse Jenkins:

Thank you.

Leah Stokes:

Thanks for having us.

Share this post