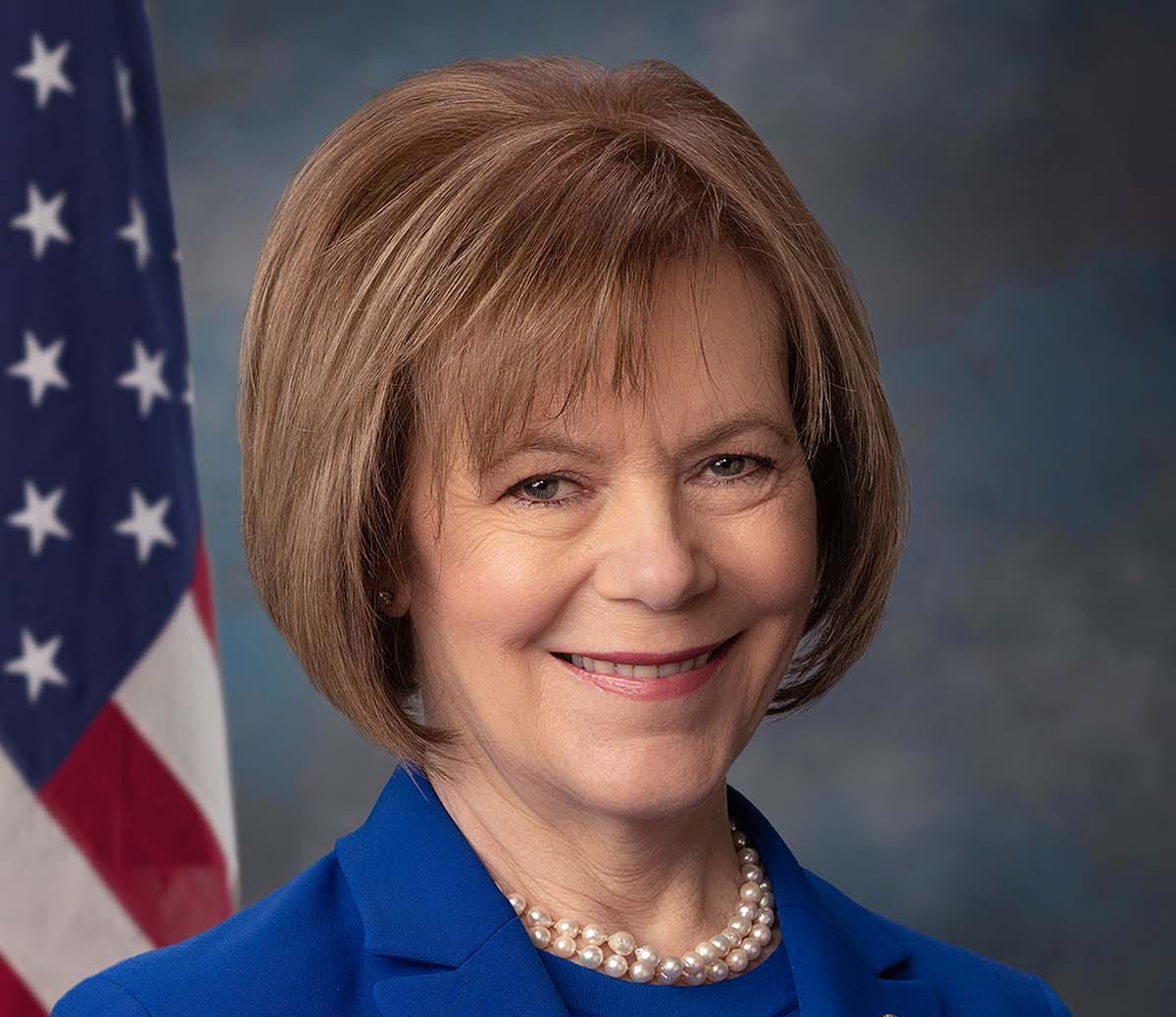

In this episode, Sen. Tina Smith (D-MN) discusses a policy that she has proposed in the Senate and is working to get included in the upcoming reconciliation bill: a Clean Electricity Payment Program (CEPP), which would aim to reduce carbon emissions in the US electricity sector 80 percent by 2030. She also shares some excellent thoughts on the filibuster!

Full transcript of Volts podcast featuring Sen. Tina Smith (D-MN), September 1, 2021

David Roberts:

There are lots and lots of policies being discussed for inclusion in the Democrats’ upcoming budget reconciliation bill, from a childcare tax credit to universal pre-K to a wide range of climate and clean-energy measures.

According to the office of Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY), the climate provisions in the bill would collectively reduce total US greenhouse gas emissions 45 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 — getting us close to America’s Paris agreement pledge.

Schumer’s numbers have not yet been backed up by outside analysts, so they should be taken with a grain of salt for now. But what’s clear, and unlikely to change, is that the bulk of the emission reductions will come from the electricity sector — specifically, from the clean-energy tax credits and the Clean Electricity Payment Program.

As regular Volts readers know, the Clean Electricity Payment Program is a version of the more familiar Clean Energy Standard that has been modified to fit within the rules of budget reconciliation. It would set up a federal program that would offer utilities financial incentives to increase their proportion of clean energy and levy fines on those that failed to do so. Its goal would be to reduce emissions from the US electricity sector 80 percent by 2030.

As Schumer’s graph shows, the Clean Electricity Payment Program, in combination with the extension and expansion of the clean-energy tax credits, would be responsible for almost 42 percent of the bill’s total reductions.

To hear more about the program and how it will work, I talked with Minnesota Senator Tina Smith (D), the policy’s sponsor and its greatest champion in the Senate. Smith is one of the handful of senators with in-depth knowledge of the dynamics in the US electricity sector, and she’s deeply involved in budget negotiations, so I was excited to ask her about how the program would work, what kinds of jobs and projects it might produce, how it might affect coal states, and of course, because I am me, what she thinks about the filibuster.

Senator Tina Smith, thank you so much for coming on Volts.

Sen. Tina Smith:

Well, thank you, David. It is terrific to be with you.

David Roberts:

We're going to talk today about clean electricity policy and the politics of getting it passed, which are two of my very favorite subjects in the world, so let's just dive right in.

Senator Smith, I’m pretty confident that Volts listeners are familiar with state-level policies, renewable portfolio standards or clean energy standards at the state level, that mandate that utilities in the state increase their proportion of clean energy. It’s a regulatory mandate passed by the state government; these are familiar, there are dozens of them across the country.

The Clean Electricity Payment Program that you have proposed is not quite that. So why don't you start by telling us what it is and how it is similar and different to these more familiar state policies?

Sen. Tina Smith:

Well, the basic goal is the same. We want to move the power generating sector so that it is adding clean energy. One way of doing that is to have a regulatory framework that says, you will add clean energy, and if you don't, you'll pay a penalty. But another way of achieving that goal of adding clean power is to do what we're doing with the Clean Electricity Payment Program.

This is a plan that says: We will provide financial incentives to utilities to add clean power; there'll be a fee if you fail to add clean power; and our goal is to get, on a national average, 80 percent of our power generation from clean energy sources by 2030.

So the goal is the same: adding clean power. The mechanism is a little bit different.

I think this mechanism has some real advantages, because under a regulatory framework, adding that clean power costs money in the short term (though it saves money in the long term) and often those costs are passed on to ratepayers. With the clean electricity plan that we're proposing, this federal incentive would defray the costs that utility ratepayers would normally pay. That's the real advantage of this approach.

David Roberts:

It’s worth pointing out something I've heard from a couple of the architects: costs on ratepayers tend to be regressive, whereas federal money comes from more progressive income taxes. So you get a progressivity advantage by drawing the money from the federal pot.

Sen. Tina Smith:

Absolutely. That's exactly right.

We need to be on this path to a clean energy transition, but what you don't want to have happen is for the cost of that transition to be disproportionately borne by people who can least afford it. This is especially important to me, because the costs of the fossil fuel economy have been disproportionately borne — in bad health outcomes and in all sorts of other external costs — by poor people, Black and brown people, people who are sited right next to freeways or right next to that coal-burning power plant.

David Roberts:

The details of this thing obviously matter. I'm curious, to what extent are the details of the program fixed and in place vs. being negotiated right now? Do we know the size of the payments? Are we sure that the target is going to stay the same through negotiations? What's in place and what's still up in the air?

Sen. Tina Smith:

Well, of course, everything is in the midst of being negotiated all the time, as you well know. Negotiations will be finalized when the budget reconciliation bill is completed.

But for me, there are a couple of key aspects of this. One, the goal of achieving 80 percent clean power in the power sector nationally, on average, is set in stone. That was described in the Democratic budget resolutions that we passed at the end of the last session. That is described as the goal of the president. So to me, that's the starting point.

Then there are a couple of other things that are crucial to this. One is that this clean electricity plan is technology neutral, which means we don't say this kind of clean energy is better than that kind of clean energy, or it must be renewables vs. carbon capture, for example. That technology neutrality is clear.

Also clear is the core idea that each utility starts from where they are, and they improve from there. This is a big deal, because some utilities and regions are already well along the path of adding clean power, and others are just starting. You don't want to unfairly penalize that utility that maybe is only at 10 percent clean power.

David Roberts:

Can you expand on that a little bit? Utilities are at very different places — financially, in terms of power mix, etc. How is the plan customized on a per-utility basis? If I'm a coal-heavy utility, what does it look like to me?

Sen. Tina Smith:

If you are a coal-heavy utility, this is very much in your favor, because you need to figure out how to add clean while you have a lot of assets in coal power. Rather than having your utility ratepayers end up having higher rates in the short term because you're adding new, clean power capital infrastructure, this would help you to add clean.

You may be a utility that's only 10 to 20 percent clean; so under our plan, we would still ask you to add clean power every year at a percentage level yet to be negotiated, at a pace that is moving you strongly and speedily in the right direction.

But there's no expectation that a utility that starts at, say, a 10 percent clean power percentage must catch up with a utility in the Pacific Northwest that relies heavily on hydropower and may easily get to 85 or 90 percent clean within a 10-year period.

At the end of that 10-year period, you're going to have some utilities that are over 80 percent, and some that are below 80 percent. The utilities I speak to that are farther along will probably argue that it's harder for them to add that incremental 20 percent of clean, whereas the utility that’s starting with ample, untapped renewable resources, you could argue that they could add quicker.

David Roberts:

So there's a national average target, but it's not that each utility has to hit that same target.

Sen. Tina Smith:

That is exactly right. That's the flexibility. It makes it much more appealing to utilities that are not as far along the curve.

David Roberts:

This brings up another question. You're trying to figure out from our present vantage point what level of payments and what pace of change would yield 80 percent by 2030. It seems like it's hard to know right now exactly what those numbers are.

So if the program is put in place, and payments are at a certain level, and the pace of change is set at a certain level, and it turns out in 2024 we find out we're not on track to hit the national target, are there provisions in place to adjust those numbers as we go?

Sen. Tina Smith:

That is a great and interesting question. I'm now going to get really wonky into the details about Senate process, because what we're using here is a process called budget reconciliation, which is a budget-driven process. What that means in practical terms is that much of the implementation and the rules around how this plan gets implemented will be left to the Department of Energy. They are writing the rules, because this is a budget process, it's not a regular process.

But let me see if I can answer your question a little bit at least. One thing I would point out is that historically, the cost curve of clean power has gone down more quickly than we anticipated. So it seems to me that, particularly for solar, for which we know the cost is going down really dramatically, we are just as likely to see power added more quickly than we originally anticipated as taking longer than we anticipated.

The overall question about how the Department of Energy would write the rules to accomplish this would probably end up being addressed in rulemaking. It gets to the question of: what do you anticipate? What do you think is going to happen? The way that we've designed this is based on a ton of modeling from the Department of Energy, and also from outside groups who have expertise in modeling.

That gives us a good framework for making some assumptions about how this is going to pan out in the real world.

David Roberts:

You've said before that you don't actually expect utilities to be fined very often, since they'd be dumb not to take incentives that are on the table. But are there protections written in about where the fines come from? And how the incentive payments are used? How closely is that specified in the bill?

Sen. Tina Smith:

This gets at a real strength of the policy. First of all, the answer is yes, we want to write into this what are allowable uses for the incentive payments. It could be building out clean resources. It could be deploying carbon capture technology. It could be adding energy efficiency resources to a system, because if you think about it, if you are reducing electricity demand at the same time that you're adding clean, the percentage of clean of your overall system goes up faster. So that would be an allowable use.

I speak to utilities and power generators that have coal power plants or natural gas plants that they want to phase out, but they have a stranded asset; you could potentially use these resources to help to retire those resources more quickly.

Then, similarly, we need to have rules around who bears the cost of the penalties, in order to protect ratepayers as much as possible.

But as I said, this isn't like the old cap-and-trade mentality, where a utility is looking at this and saying, my cost of paying the fee is lower than making the investment — this just isn't set up that way. That's a strength.

David Roberts:

It's a little bit more transparent than cap-and-trade; the money is more in the headline and less something you have to deduce.

How do you pitch this program to a person — say, for instance, a friend of yours named Joe — in a coal-heavy state, with a lot of coal-related jobs? Fossil fuel-heavy states have traditionally been resistant to things like this because they feel like they're starting on the back foot. In terms of both the power mix and the job mix, how do you pitch this program to a coal state?

Sen. Tina Smith:

It's interesting. I think about answering that question from the perspective of a place in Minnesota that is similar in many ways to parts of West Virginia, which is Minnesota’s Iron Range. This is a part of my state where the bread and butter of the economy, and historically the culture and the source of pride, has been mining iron, and then taconite, and producing the iron that has driven the economy of the United States.

There is a real sense in that part of Minnesota, just as I think there is in West Virginia — though Joe Manchin knows way more about West Virginia than anybody — that this economy is getting passed by. There are new opportunities out there, but is it ever going to come to me, to my community, to my world?

That is one of the real strengths of this idea. First of all, clean power, including renewable energy, is rural energy. That's where it is most likely developed. In fact, West Virginia has abundant renewable energy assets that are waiting to be developed. If you care about wanting to be a part of this clean-energy transition — which is, by the way, going to happen — the question is: Do you want to lead? Do you want to be in the forefront of that? Or do you want to be behind?

The opportunities for West Virginia, and other states that are part of the traditional fossil fuel economy, to seize this moment, to move forward with the kinds of proposals that Joe Manchin has put forward, like the American Jobs in Energy Manufacturing Act, and deploying carbon capture and storage technology, and taking advantage of the skills and expertise of the working folks in West Virginia to drive those innovations — to me, that's all about being in the forefront.

In fact, the West Virginia University Law School just put out a really excellent summary of what moving to this clean energy future could mean for West Virginia in terms of increase in employment, growth, and state GDP, opportunity for new investment that creates new jobs. It demonstrates where the opportunity is, in West Virginia and other places.

David Roberts:

As a matter of fact, I just posted a piece yesterday about West Virginia and that study. One of the interesting things about that study is it shows pretty substantial benefits for West Virginia, but the analysis was done before the Clean Electricity Payment Program was on the table. So the Clean Electricity Payment Program would more than double all those benefits; the amount of money that could flow into the state from federal coffers just through the Clean Electricity Payment Program is pretty enormous.

Sen. Tina Smith:

It is. It's such a perfect case study of how, the way that this is structured, along with the other clean and renewable energy tax credits, is actually a giant boost to employment and jobs, and not a gloom and doom, “we're going to all have to sacrifice because the climate is warming” mindset that has too often been the way that these issues have been approached.

David Roberts:

Of course, the question for West Virginia is: compared to what? What is the alternative? Coal is on its way out, according to the markets, so it’s now or never.

Sen. Tina Smith:

That's exactly right. Coal demand has gone down substantially, and as I said, this transition is occurring. A lot of times people will point to, why should we make sacrifices in the United States when we see China increasingly being a source of carbon pollution? What I like to point out is that China added substantially more wind and solar resources than the United States over the last 10 years or so. They are making significant investments in wind and solar, not to mention electric vehicles and other new energy technologies. So, let's lead on this.

David Roberts:

How much of a sacrifice is it, really, to get more GDP and more jobs and less air pollution and better health outcomes? Pretty nice sacrifice as sacrifices go.

Sen. Tina Smith:

But I think we also can acknowledge that, as a very dear friend always loved to say, everybody loves change as long as it happens to somebody else. You could understand why Minnesotans who live on the Iron Range, or coal miners that live in Wyoming or West Virginia, are questioning whether at the end of the day these benefits are actually going to come to them and their communities. So it is incumbent upon us to make sure that we're putting in place the policies that make sure that happens.

I've spoken with Secretary Granholm about this a lot. She gets this, not only from being head of the Department of Energy, but being a former governor. You have to have a real place-based strategy for making sure that these benefits don't just happen anywhere, but they happen specifically where they need to. It’s the same issue as the environmental justice needs we have as well.

David Roberts:

A couple of broader questions about the politics of this. One of the vexations about US policy these days is that it seems to swing back and forth wildly depending on who's in charge. We saw Obama pass a bunch of stuff, and then Trump take over and spend four years frantically undoing it all, and now it's being redone. Is there anything about the Clean Electricity Payment Program that will make it resilient, even if Republicans take back over Congress and/or the presidency?

Sen. Tina Smith:

What you just said makes the strong argument for why it is so important to make these kinds of policy and budgetary decisions legislatively, rather than through executive action. You're absolutely right. When Obama was so tired of being stymied by a recalcitrant Congress, he took steps through his executive power with the Clean Power Plan, for example; that and other steps that he took around renewable fuel standards and so forth are relatively easy to wind back.

But I think there's another lesson here, which is when you legislatively pass budget bills that are not only smart policy but are broadly approved of by the public, it becomes very difficult to unwind them. I look at the case of the Affordable Care Act — the Republican Party opposed that, spent how many years, over and over and over again, tried to unwind it, with no policy to replace it, because they really didn't know what their other idea was — that became more and more popular. Ultimately, they failed in unwinding it because people liked it.

The same can be said of this clean electricity plan, because polling data shows that this is the direction people want. Businesses know this too. This is why businesses like Walmart, and Kroger, and others, are saying, oh, our customers want more clean power. This is what they want. There's a lot of public pressure to move in this direction.

David Roberts:

Notably, both large employers in the state of West Virginia.

Sen. Tina Smith:

Yes. It's interesting, I was just looking at this: The percentage of people in West Virginia that are employed in coal is 2 percent. So again, similar to Minnesota's Iron Range, it looms large in the history and the economic foundation of the state, but it's a relatively small percentage.

David Roberts:

In some ways this is the energy analogue of Medicaid expansion, in that it is the federal government saying: you need to do this; let us pay for it. Some states have resisted Medicaid expansion, but none who have accepted it have reversed it. Once you're getting it, you don't want to stop getting it.

Sen. Tina Smith:

That's right. To further that analogy: We could conceivably have designed a plan that would have been state-based rather than power generator-based, and I think that your point is one of the reasons why it's good that this is power generator-based. They're going to be making investment decisions and economic decisions that will support advancing this.

David Roberts:

Right, and it’ll be hard to unwind those.

On a broader level, some people in the Senate have raised worries about spending too much money and running up the deficit and exacerbating inflation. One, do you worry about that at all? What's your take on the worry about deficit spending? And two, if the overall spending number gets haggled down, how safe do you feel that the energy money is in those negotiations? Is it going to be on the chopping block if there are cuts to be made?

Sen. Tina Smith:

Well, not if I can help it.

Broadly speaking, when we are looking at the overall size of the Build Back Better budget, I don't hear people in Minnesota saying, “Oh, Tina, this amount of money is too much, $3.5 trillion is too much, but $3.1 trillion would be OK.” I don't think that that's how people are thinking about it. They're thinking about, how is this going to affect me and my family? That's sort of the cliche of talking about legislative policy, but I actually think that it's real.

Certainly, as we go through this negotiation, and we have to come up with a plan that is agreeable to all 50 Democratic senators, there's going to be some haggling and some back-and-forth. To me, the most important thing is that we don't give really strong policy and budget proposals like this a haircut so that they don't work anymore. We’ve got to make sure we don't do that.

But the other question you asked is an interesting one too, about budgets and deficit spending and so forth. I would just point out that when we write this bill, at whatever size it is, it's going to be paid for. So that's a good thing. In fact, when you look at how Americans feel about the Democrats’ budget bill, one of the things that they like the most is that it is paid for by asking the wealthiest Americans and big corporations to pay their fair share. That seems fair to them, and it seems right. It generates resources in order to do these things that are going to build up our economy and lift up our communities in powerful ways.

David Roberts:

I have been somewhat confused that the deficit concern seems to come up again and again, even in the context of a bill that is explicitly paid for. It seems like something people say almost by instinct now in DC.

Sen. Tina Smith:

That's right. In Washington, David, maybe you've noticed, there is sometimes a disconnect between rhetoric and reality.

David Roberts:

What?! Yes, I'm skeptical that there is any human being that has genuine concern about the deficit as a primary motive in their heart. That always sounds like an excuse to get at something else.

Sen. Tina Smith:

Right. The bipartisan infrastructure bill that is moving through Congress, that passed the Senate with 69 votes, is about investing in infrastructure, including some important strategies for advancing this clean energy transition with electric vehicles and charging stations — that was bipartisan, and probably not completely paid for. I would say, shoot, you're investing in roads and bridges and broadband infrastructure that's going to be around for 60 or 70 years; that's what states do all the time, is borrow to pay for long-term assets. So to me, that's not a big deal.

David Roberts:

Right, and putting in place long-term assets drives economic growth, which is the best thing for wiping out a deficit. OK, we won’t get stuck ranting about deficits, I could do this all day.

Also on the broader politics of this: energy and climate people are watching this unfold from the outside with white knuckles. There's this two-track strategy: you’ve got the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and then you’ve got the reconciliation bill, which together are supposed to be the full agenda, the full package.

But there's been a lot of fights and strains lately about whether to keep those two bills linked; there was a fight in the House about it just last week. Do you think that linking those two bills is the right way to go, and do you think that you're going to be able to keep them linked?

Sen. Tina Smith:

It is absolutely right to link these two bills. To me, they're rafted together. My support for the infrastructure bill, which I think is a good bill, is contingent on understanding that we have all agreed that we're going to move forward the reconciliation bill together. The two-track process divided up a broad agenda into two chunks, but we still need to pass that broad agenda for the good of the American people and for the good of people in my state.

One of the things that I've learned about legislating in the relatively short time that I've been in the Senate is that you have to have a clear idea of where you're heading. In this case, the Democrats are heading towards passing these two big bills. Then you have to be flexible and incremental about how that happens as you move through the process.

And then there's just a pileup at the end, and then you get it done. I'm not looking forward to the pileup, but I expect that it’ll happen. That is the reality of working in a democratic process, where there's 100 people in the Senate and 435 people in the House that all have very clear ideas about how they want to get things done.

David Roberts:

In my political lifetime, I’ve never seen a situation quite like this, where there are 50 Democrats and every single one of them has to agree.

Sen. Tina Smith

I know. It's kind of terrifying.

David Roberts:

It gives every single one of them the ability to blow the whole thing up. People are focusing on Manchin and Sinema, but really, every senator could blow it up. But at the same time, if they blow it up, they all go down together. There's going to be a game theory study about this some day.

Sen. Tina Smith:

That’s right. But at the end of the day, this broad agenda is broadly popular. It is what Joe Biden ran on; it’s not like it got pulled out of thin air. It's what he talks about, and what so many of us talked about during our campaigns in 2020. So you're right: the price of taking this down because you didn't get absolutely everything you wanted, because it's a little bit more money than you wanted to spend, that seems to me to be a heavy price.

David Roberts:

There's no half failure here. It's all success or all failure.

Sen. Tina Smith:

One for all and all for one.

David Roberts:

Along the lines of unity, and the question of how to legislate in today's politically dysfunctional atmosphere: What is your take on the filibuster? This is not directly related to the reconciliation bill, but in a sense, Democrats are forced now to basically run the vast majority of their agenda through the reconciliation process because of the filibuster. That shapes what policies they're capable of doing and excludes some policies that people would like to see, like voting reform, potentially immigration reform, etc. So what's your take on the filibuster personally, and the attitude of the Democratic caucus about the filibuster? Do you see that changing at all or shifting?

Sen. Tina Smith:

Personally, I believe that the filibuster rule ought to be thrown out, and I didn't come to that easily. I believed for a long time that it was important that hard-won rights couldn't be taken away by a simple majority in the Senate. I cared about that one, because I spent a lot of my life working on women's reproductive rights, and I imagined a world where a majority of the Senate could strip away those incredibly precious rights.

But my perspective on this has really changed. I came to understand how fundamentally undemocratic it is to require a supermajority to get anything done. I also came to see that the filibuster, which is the right, basically, to debate or to talk as long as you want to — that that isn't really happening in the Senate these days. It's not as if Mr. Smith is going to Washington and making impassioned speeches on the floor of the Senate. Mr. Smith is sending his staff member down to say, “I’m putting a hold on that piece of legislation.”

David Roberts:

Right. It's a memo.

Sen. Tina Smith:

Exactly. Truth be told, the Senate already structurally leans towards giving strong power to less than a majority of the voices, because the 50 Republicans in the United States Senate represent only about 43 percent of the American public. So what do we do because of the unwillingness of some to change these rules that also have an ignominious history? We develop workarounds like the reconciliation package, that allows us to pass significant and important legislation with a simple majority at the end of the day. It doesn't make any sense.

David Roberts:

It's not what you would write out if you were sitting down to write out a coherent legislative process. How common do you think that opinion is in your caucus? It’s either got to be done in the next two years or not at all. Do you think there's any chance of opinion thawing or shifting within that timeframe? Or is this just something people should write off?

Sen. Tina Smith:

It’s hard for me to see a world where people just change their minds on the filibuster. However, I would look for other ways that Senate rules could be reformed so that they make more sense, so that the Senate can function better, and maybe, possibly, changing the rules around ending debate for particular pieces of policy — though that's maybe more my wishful thinking than anything else. We have to seize this moment that we have to take action on climate, a moment that I don't think will be replicated for many years. We don't have time to waste. There is an urgency of seizing this moment, and that's what a lot of us are working really hard to do.

David Roberts:

Well, on that note, thank you for your work. Thank you for pushing so hard for this, and thank you for taking the time today.

Sen. Tina Smith:

It's great to talk with you. Thanks a lot.

Share this post