In this episode, MIT Professor David Hsu discusses a paper he wrote that charts the history, evolution, and current fortunes of community choice aggregation, a tool whereby a community can take ownership over its own energy procurement. It is the rare example of energy democracy breaking out in America's monopoly-dominated system — a good news story in an era of bad vibes.

Full transcript of Volts podcast featuring David Hsu, March 16, 2022

David Roberts:

In the late 1990s, a small group of policy entrepreneurs snuck a modest provision into a larger electricity-restructuring bill passing through the Massachusetts legislature. It was so obscure that the media scarcely noticed it — it's not even clear if the governor's staff knew it was in there.

The policy had a different name then, but today it's come to be known as "community choice aggregation." The idea is simple: communities can band together and take over energy procurement from their electrical utilities. The utilities remain responsible for infrastructure and billing, but the communities get to decide where their energy comes from and what kind of energy it is.

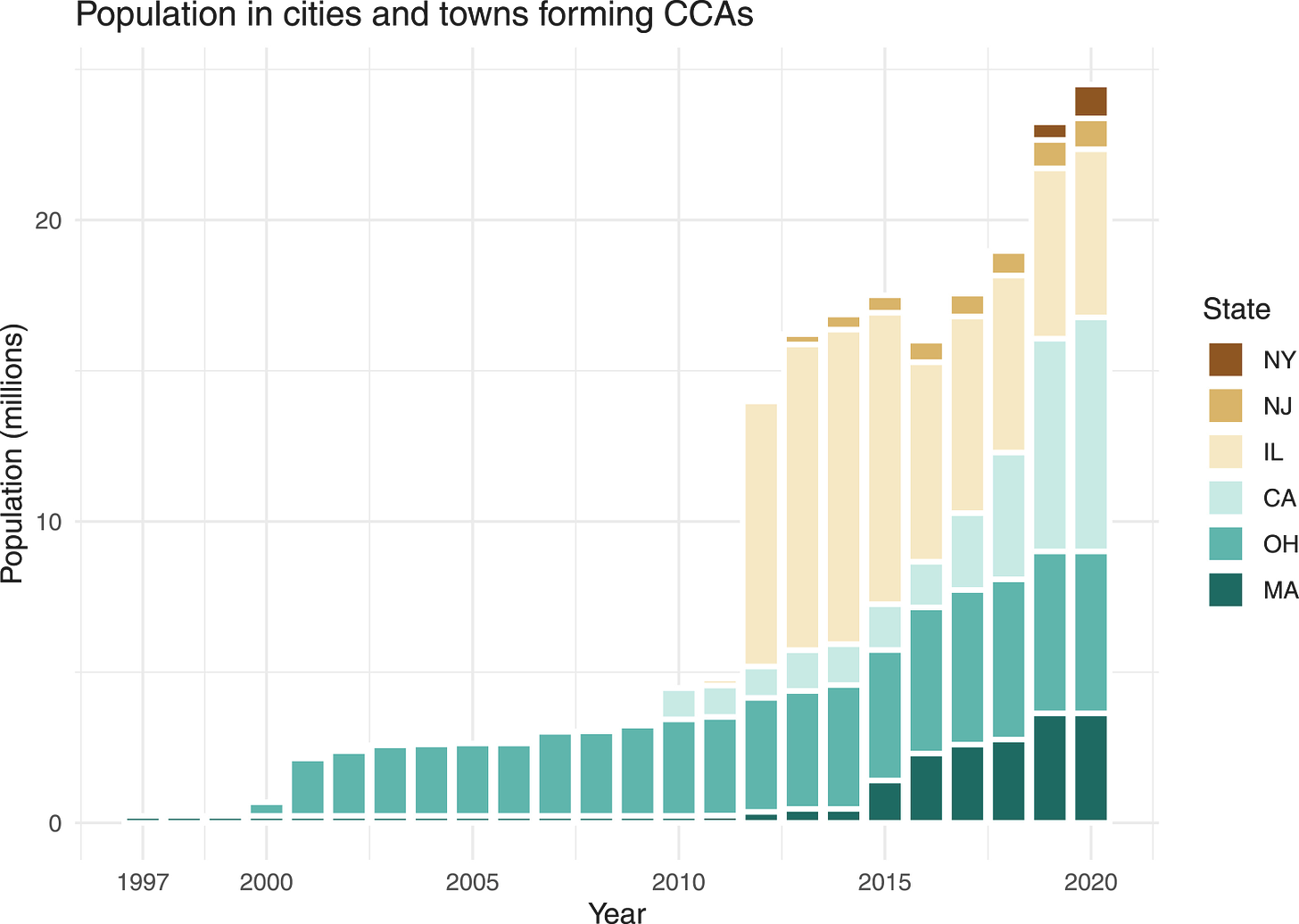

Since that humble beginning, community choice aggregation has taken off. Currently more than 1,800 communities in six states, comprising 36 million customers (some 11 percent of US ratepayers), choose their own energy supply.

There are more states and communities considering community choice aggregation every day. It is, in our otherwise grim times, a hopeful story about climate policy — a true demonstration of the power of grassroots activism to make lasting change.

David Hsu, an associate professor of urban and environmental planning at MIT, has researched the origins and growth of community choice aggregation and recently published the results in the journal Energy Research & Social Science.

I thought I would have him on the pod to talk about how this unassuming policy with the difficult-to-remember name grew from such modest beginnings to such sprawling size, so fast. We also discussed the differences among different community choice aggregations, the kinds of innovations they are spawning, and their future trajectory.

Without further ado, David Hsu, welcome to Volts.

David Hsu:

Thank you for having me. I appreciate the invitation.

David Roberts:

What is community choice aggregation? How many are there now, and where are they?

David Hsu:

Community choice aggregation goes by many names, which I think is why people haven't recognized how far it's spread. It’s called community choice energy in Boston, governmental aggregation in Ohio, and municipal aggregation in Illinois and Massachusetts.

There are about 1,900 municipalities that have so far chosen to use community choice aggregation. It’s authorized by state legislation in 10 states: Massachusetts, Ohio, Illinois, California, New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Maryland, Virginia, and Rhode Island. These 1,900 municipalities represent about 36 million people, or about 11 percent of the US population.

Basically, the local government, if enabled by state legislation, can procure energy directly through a competitive wholesale market. It can be initiated by elected officials in some states; in other states it has to be initiated by ballot referendum.

David Roberts:

Interesting. So in some places it can be done without a vote from voters.

David Hsu:

Yes. But those officials are still accountable to voters through their jobs.

David Roberts:

The utility for a city does several things, one of which is procure energy. Community choice aggregation is turning that part of the utility’s job over to the city, but the other parts of the utility’s job are still done by the utility, right?

David Hsu:

The utility still delivers the power through their distribution network, which they have a regulated monopoly on. But the community choice aggregation can sign the procurement contract, and they can do other things like local economic development, build and distribute energy resources – depends on the state and depends on the aggregation.

David Roberts:

This is only possible in restructured electricity markets where there is a wholesale electricity market, is that right? You couldn't do this in an area with a fully vertically integrated utility, could you?

David Hsu:

Right. The legislation almost always follows restructuring – usually hot on the heels of restructuring, sometimes a little later – but it has to be in a restructured market, as far as I know.

David Roberts:

This has become a very big deal, as you say – 1,900 municipalities, 36 million people. A substantial portion of the nation's ratepayers are now involved in these. But the beginnings were incredibly modest. Tell us the story about the germ of this idea and where it came from.

David Hsu:

It starts with Scott Ridley, a journalist working in Massachusetts in the 1970s. He becomes a consumer environmental advocate and activist, because a lot of people at that time are protesting against nuclear power in Massachusetts and elsewhere. Through his journalism, he's also researching the borrowing capacity of cities, and what laws govern how cities borrow money.

At the time, the utility that's building the Seabrook nuclear power plant is encountering cost overruns, like all nuclear power plants in the 1970s. They want the local cities and municipalities to borrow for them using their tax-exempt rate and to buy a share of nuclear power.

It brings his consumer advocacy interests and his environmental interests together. He starts writing against nuclear power and this financing plan. He forms an advocacy group called the Clamshell Alliance, and they, along with many other groups, help defeat an additional unit in the Seabrook nuclear power plant.

From that he links up with a historian at University of Massachusetts Boston named Richard Rudolph. They wrote a book together in the 80s called Power Struggle.

David Roberts:

Great book, notable book. Everybody should read that.

David Hsu:

I’m curious how many people know about that book. It comes up here and there, but I sometimes feel like it's not as well known as it should be. When I started researching aggregation, I realized this book had been on my shelf for a couple of years and I hadn't read it.

It's a political history of utilities and ownership of the utility system. It's interesting because it's written for a general audience, but it basically details how we got munis, and how we got IOUs, and how we got regulation. And it’s written as a political struggle.

David Roberts:

For those who might not have the background education in geekery, an IOU is an investor-owned utility – more or less the standard model in restructured areas where there are competitive wholesale markets. A muni is a municipal utility – that's basically a municipal area taking over everything and becoming its own utility, a publicly owned utility that serves its energy and owns all its distribution infrastructure and bills and does everything else.

David Hsu:

After Scott writes this book, he and Richard Rudolph tour the book around public power advocates and nuclear advocates. In the late 80s, he goes off to Chicago to try to help them renegotiate their municipal franchise. The franchise agreement is the agreement by which the city allows the investor-owned utility to use their rights of way and their property to build the poles and wires that serve electricity. (Chicago is the birthplace of the electric grid with Samuel Insull in the 1880s, so this is the third time they’re re-signing a franchise – every 40 or 50 years. Turns out, Chicago's re-signing a franchise right now.)

The municipalization fails, because Harold Washington, the mayor at the time, dies of a heart attack. So municipalization doesn't happen in Chicago, and the franchise renegotiation doesn't happen.

Scott goes back to Cape Cod and finds out that it has really high electricity rates. Cape Cod is one of the fastest-growing regions in the country at the time. A local county official named Rob O'Leary has helped set up a county planning commission for the first time, and another local activist named Matt Patrick has a nonprofit focused on energy efficiency. The three of them get together.

Electricity restructuring is in the conversation all over the country at this time. The three of them start talking about what this might mean for local towns and cities, because they already have incredibly high electricity rates. Scott has all this experience researching the political history of how utilities and towns and cities interact, or really conflict. They decide that they want to try to write a role for cities and towns into the new landscape that might be coming with restructuring or competition.

David Roberts:

For those who aren't familiar, once upon a time, all utilities were what's called vertically integrated monopolies. They owned everything: all the infrastructure, all the power plants. They did everything. There was this wave of restructuring, as it's called, in the 80s, 90s, and early 2000s, whereby they broke those utilities up such that the entities that owned the generators competed in wholesale generation markets, and the entities that owned the power poles and billed customers became what are called wires companies, which just owned the infrastructure. Those became two separate entities. The idea was to introduce competition into the power game and therefore reduce prices.

David Hsu:

They also introduced retail choice programs at the time to try to give consumers a choice on the retail side – like individual residential home customers to try to pick between power companies – with varying degrees of success.

David Roberts:

Notably, the wholesale side competition has taken off and is mostly viewed as a success. Whereas retail choice, having individuals be able to choose their power companies, as good of an idea as it sounds, has not really succeeded in the same way.

David Hsu:

So Matt Patrick, Rob O'Leary, and Scott Ridley start talking about an energy plan for the Cape. They call up State Senator Mark Montigny, who at the time is chairman of the Energy Committee, and his advisory staffer, Paul Fenn. They start talking about what kind of thinking around competition is coming – through the legislature, through the governor, nationwide.

They write a trial bill in 1994 or 1995. It gets killed. The chairman of the committee moves to another committee. Paul Fenn leaves for California to get involved in politics.

Where the story really picks up is that there's an aspect of direct democracy. New England has this tradition called town meeting; it's something that originates in the 1700s, before the American Revolution. In these small towns and villages you get together for this annual meeting, and anyone can introduce a resolution. It's a uniquely New England thing.

Ridley, Patrick, and O'Leary start visiting towns to try to introduce non-binding resolutions, e.g. “we simply want to express as a town that if there are reforms in the electricity industry, we would like to be able to make a choice of who we get power from as a community.”

They tell these great stories of introducing these non-binding resolutions, like they’d go to the utility and the utility guy would literally laugh at them. He would say “this is my territory, this is never going to happen.” He would laugh them out of the office.

When they start passing these non-binding resolutions, the utilities do two things. They first ignore this completely, and that actually builds support among communities that say “we expressed our desire for this. We'd like to see a change. We'd like to have a choice.” And then the utility tries to come in and undercut some of the proposals.

It builds support among a lot of small towns and communities in Cape Cod, in western Massachusetts. Traditionally, those communities don't feel like they have a voice in the legislature. But after communities express support for this, these three activists are advocates; they go to the legislators and say “we have 20 or 30 towns that are interested.” Legislators start listening.

There's this whole restructuring process that we tend to talk about that's a negotiated settlement between the governor and utilities and unions and environmental activists. It turns out, if you look at the archives, those negotiated sessions almost never mention this aggregation, because the legislators put it into the bill almost without the governor's knowledge. The only memo I can find of the governor's staff even talking about it is a memo from the morning of the bill signing.

This is what they pass around the staff, and the governor signs it that day. Somehow community choice aggregation makes it into the bill. And then it languishes; about 10 Cape Cod communities spend about three to five years trying to implement this new idea, which everyone is against.

David Roberts:

I find it delightful that this thing that now is so huge passed almost without notice. It reminds me of when I was in Berlin eating schnitzel and spaetzle with Hans-Josef Fell, the famous German legislator and clean energy activist. He co-authored Germany's feed-in tariff bill, which went on to utterly revolutionize German electricity and arguably global electricity; it provided a massive amount of German demand for that early growth of solar. He told me the exact same thing – there was no big fight. No one noticed. No one cared. No one thought it would do anything.

If you're a policy entrepreneur, this is the sweet spot, right? You sneak it in and it grows like kudzu, and then it's too late to stop once they notice it.

David Hsu:

One of the activists, Matt Patrick, decided they should try to get some of the system benefit charges (the charges that utilities collect to do energy efficiency) because the restructuring was a negotiated settlement between the utilities, the regulators, and the unions to some extent. The utility said “okay, we'll do energy efficiency if you allow us to collect ratepayer money to put into Mass Save (its very successful energy efficiency program).”

But Matt Patrick, two weeks before the bill signing, decided “we deserve some of those funds in Cape Cod” because he was an energy-efficiency activist. He wanted to direct it to Cape Cod because they felt like they could do energy efficiency better and that the state wasn't doing energy efficiency in a way that benefited the Cape. So he wrote that section and put it in the bill; nobody noticed.

In a way, that's the kind of amazing part, that other states haven't necessarily had clauses like that. Clauses like that exist because Matt Patrick decided to put it in, as far as I can tell.

David Roberts:

This is really a story of a handful of people taking enormously historically important action. It's a story about what a small group of people can do.

David Hsu:

I was looking for that story, and it found me. In 2017, my students were all depressed (for obvious reasons), and I was looking for a way to tell them “you can change the energy system by starting small and focusing on something and finding your policy window.” The story got deeper from there, but it amply fulfilled what I was looking for, even if I didn't know that's what I was looking for.

David Roberts:

So Massachusetts passes this behind its own back without noticing. The implementation took a while. Another policy lesson here: it's one thing to pass something, but implementation is also important and crucially comes down to the actions of a handful of people, again, to make it work. Who figured it out on the ground?

David Hsu:

A grant writer named Maggie Downey joined them. Today she's the head of the Cape Light Compact, the current name of that first CCA. Scott stuck with it as a consultant, helped them work out the energy efficiency program and helped them negotiate their first contracts. Matt Patrick and Rob O'Leary stayed involved; they later went on to the state legislature themselves, hopefully paying attention to activists like they used to be.

Regulators didn't want to help even though it was passed legislation; they didn't want to translate that legislation into action. Generators didn't want to sign contracts with them at first because they were an unknown entity. Some generators, like Enron, didn't want to sign a contract with them until Enron started realizing that with their whole idea around consumer choice, these local cities and towns could acquire customers much more cheaply than they could do themselves. They learned this lesson in other cities and states too.

The Cape Light Compact – 10 or 11 cities in the first year – started doing advocacy right away, because it had already built up local community. There was a settlement as part of the restructuring where some $25 million would have gone from the sale of power plants to Cambridge (Harvard and MIT would have benefited from that), and the compact right away did advocacy, filed essentially a claim in the restructuring process, and won the $25 million back to the Cape, which probably meant a lot more in the 1990s than it does now.

The key thing is that they had already done the organizing in local communities. People had already agreed to do it; they'd already started working collectively through cities and towns. These four activists stuck with it. They had the expertise and knowledge to get this going, but it still took them three to five years.

They were struggling against what's called a standard offer, which exists in almost all restructuring states: legislators set the prices low to make sure customers want to be happy after this legislation, but they actually set an artificially low market rate and preclude new entrants from coming in. That stopped the Cape Light Compact from charging the market price for three to five years until they found a loophole. They managed to offer power just to new customers, and they got going after they managed to start offering power at market rate.

It was a jerry-rigged beginning for the first three to five years. They were trying to figure out problem after problem. One of the governor's staff said “nobody deserves more credit than them for just sticking with it when no one else believed in it. They believed in it and they made it work.”

David Roberts:

That particular CCA is still around and well-regarded.

David Hsu:

It's expanded to Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket, islands off the Cape. I think they’re up to 25 towns now. They regularly win energy-efficiency awards. They're still a small staff, but they are quite active, and they're doing cool stuff like building electrification too.

David Roberts:

An interesting part of the story is that there was not direct spread to other states. It was indirect, word-of-mouth spread, and other policy entrepreneurs and other states took it and ran with it.

David Hsu:

The word that academics would use is “policy diffusion.” Another academic, pretentious-sounding phrase that we use is “epistemic communities” – communities of lawyers and energy advocates start hearing about this through journals. Another theory is policy imitation: states start imitating other states that are doing the same thing.

All these states are talking about restructuring at the time, and every time they talk about restructuring, the idea spreads. In every state they start thinking about a similar idea because it's been proven to work – or at least it's proven that it can be passed – in Massachusetts. But every state writes their legislation a little differently.

It's interesting how sometimes these historical things really come down to weird coincidence. One of the people associated with early aggregation in Ohio told me that he thought that part of the reason why the idea took off is that one of the Massachusetts activists who had a fairly Irish name came out and talked to all these Irish mayors in northeast Ohio, and they picked up on the idea to put it into their restructuring legislation too.

David Roberts:

Now 36 million people in 1,900 municipalities are involved in these and they're still spreading rapidly. They began as a remora fish attached to restructuring, and restructuring seems to have lost momentum, but are new CCAs still spreading?

David Hsu:

Yep. In Massachusetts, there was only the Cape Light Compact for such a long time. It started to pick up five or 10 years ago, and about a third of the cities and towns in Massachusetts chose to do it over the last five years. Now we're almost up to about half of the cities and towns in Massachusetts. Most importantly, in terms of sheer size, the city of Boston chose this a year or so ago and started serving power in the last year.

David Roberts:

Didn't Chicago also do it?

David Hsu:

Chicago had an aggregation in 2011-2012. A lot of the advocates decided that they wanted to see this happen in Illinois, the utilities didn't fight it at the time, and Chicago chose aggregation.

An insane number of cities and towns in Illinois chose to do aggregation because the utilities had fairly long contracts locking in a high rate of power. In almost every market, because the CCAs have come late and solar power has gotten progressively cheaper, the CCAs enter markets where the price of electricity has been going down. So when they sign a new contract to the market rate, they almost always come in lower than utility long-term contracts have been. In Illinois, somebody said, you could almost do nothing and get 20 to 30 percent savings for your community. Chicago signed an aggregation; 90+ percent of the Illinois population signed up for these aggregations.

When Rahm Emanuel took over as mayor, he was dealing with financial difficulties, he had a few priorities, and he said the aggregation no longer was saving Chicago money, so they got rid of their aggregation.

The good story about Illinois is that despite going to such a high percentage of the population, it's been remarkably sticky. Fifty percent of the population in Illinois is still signed up for aggregations. Those could go away if the utilities become more competitive in price.

Ohio has also been remarkably sticky. It's built up an aggregation over time and they're almost at 50 percent of the population, despite all of the different energy debacles that have occurred in Ohio over the last 10 or 20 years.

David Roberts:

One of the common features of CCAs is not only can the municipalities themselves pull out when they want to, but individuals within them can opt out.

David Hsu:

Another lesson I was trying to teach my students is that if you stick with legislation and keep on working on it, and iterate it, then you can introduce new things that overcome some of the obstacles. What the activists did after the first bill went down in Massachusetts was to write this thing called opt-out aggregation, where anybody in the city and town can simply say “I'd like to go back to the utility, thank you.”

Most cities and towns around the US don't have opt-out rates of higher than 5-10 percent. But they couldn't get legislative support until they put in this opt-out clause.

David Roberts:

The word “choice” is political magic.

David Hsu:

The rhetoric of choice is really powerful. We need to think about some things in terms of choice, because that builds support.

David Roberts:

Are there differences among and between CCAs in general that are significant and worth noting?

David Hsu:

Especially in California, where CCAs have been growing like wildfire for the last few years, you see the differences among them – both when they start up and also when they're in process or execution and the directions they take.

The first couple of CCAs started in Marin County and Sonoma County, generally wealthier enclaves in California. They started off by trying to offer a higher percentage of clean energy than the utilities were at the time, and also offering 100 percent clean energy options. With a new option called Local Sol, you can buy 100 percent California power.

Some of the CCAs more recently, especially in areas off the coast in California, have been marketing in terms of getting price savings for customers.

One exciting thing to me is that a lot of the CCAs are marketing in terms of local economic development and green jobs. Local control power is, like you said, political magic. It's something that is resonant in lots of places because you have utilities in California that, frankly, people hate.

David Roberts:

Let me run a semi-skeptical take by you.

You have these giant, old utilities that have a lot of old practices and legacy infrastructure investments that they're still paying off. The price you're paying to the utility is a combination of the sticker price of the electricity itself and all these old legacy investments.

If you're a town, you can opt out and say “we're not going to pay any of those legacy investments. Instead, we're just going to pay the sticker price for energy; we're going to buy our own energy.”

On the one hand, of course you can get cheaper delivered electricity that way, if you're not having to pay the legacy costs, but on the other hand, you can see why that's a limited strategy. If everybody does this, then the legacy costs are stranded.

Isn’t the fact that a CCA can get cheaper power an artifact of the fact that they're not tied to these legacy costs? This is a worry that they've raised in California – if everybody opts out, who's paying for all this old stuff?

What do you make of that take?

David Hsu:

You have to distinguish between the legacy assets of the utilities being the legacy physical assets, literally poles and wires and easements and rights of ways, and then the market contracts they have for power.

With the latter, CCAs do come in to the market later, when electricity is cheaper, and so they do undercut utilities. CCAs don’t necessarily beat utilities on price very much just in terms of the sticker price of the power, because when the utilities sign a new contract, generally any of the communities that went in for sheer opportunistic price savings basically lose those opportunistic price savings.

David Roberts:

Right, sooner or later the utility is going to get out of those old contracts and get into new contracts with cheap power, and then the price differential disappears. Then what, the CCA just goes away?

David Hsu:

The opportunistic price savings are not actually a great rationale to do CCAs.

David Roberts:

Aren’t they sold on that basis, though? Hasn’t that been the primary sales pitch?

David Hsu:

I don't think it's necessarily the primary sales pitch. Some CCAs are explicitly in places where people say “we would like to buy more green power.” I don't know this for sure, because I wasn't in Marin County in 2010, but some of those early CCAs may have actually been sold in terms of “we think we can get the same price for power, but we can get greener power.”

The more successful CCAs aren’t necessarily advertised or marketed in terms of having price savings. I do agree with you that some CCAs have marketed in those terms. I find very little evidence, at least from our limited history, that those savings are going to be durable.

David Roberts:

Do we know currently whether CCAs are paying less on average for their power?

David Hsu:

This is a hard thing to study because CCAs vary by state. All the restructuring and all the state markets are different. I've seen one presentation recently that showed CCAs saving something like 3-5 percent in California. A few of the CCAs cost a little more than the utility comparison.

You can't say a huge savings, though some of them save 10 percent off the bat until the utility signs a new contract. But the exciting thing is that local control part. Some people are willing to pay the same amount as long as they can have more local control.

David Roberts:

I can totally imagine a certain set of communities opting to pay as much or slightly more for cleaner power. I’m cynical about whether you're going to get something of national scale on that basis.

David Hsu:

What do you want to happen nationally? If you're going to judge CCAs by that, you have to judge them fairly. What's the alternative: utility monopolies that we've had for more than 100 years?

Or, what else is happening at CCAs besides the price savings? A lot of the CCAs are doing things that we haven't seen utilities do. The Cape Light Compact has a building electrification pilot; they have energy-efficiency programs for all kinds of residents. City of Boston has a special rate structure to protect low-income residents from price increases. Those are the things that you can do locally, and those are the things that are really well-tailored to the political environment of the CCAs.

David Roberts:

CCAs are not tied to the rate structures of the utilities, right? They can come up with their own rate structures?

David Hsu:

I don't want to speak for all states, because you can't keep track of all these municipalities at some point. In Massachusetts, we have both the generated power and the delivered power; they can charge their own rate structure for what they procure, which is the generator power, and the delivery charge is probably passed on to them from the utility.

David Roberts:

Rate design is one of the needed areas of reform, and it's something that utilities are slow to do.

David Hsu:

The reason why it's worth thinking about rate design at the local level is that this is all designed out of Boston City Hall. Those officials are accountable to the voters. Boston Municipal Energy basically put together this rate structure for the aggregation.

The other exciting thing is the CCAs are bringing energy staff into City Hall for the first time since the 1970s. Cambridge has an energy manager, they're on their second aggregation. Somerville, Medford, Brookline have energy managers. Those are also the cities that are out in front and thinking about what kind of local energy resources they can build.

David Roberts:

Once you have local energy expertise and local energy management, those people can work with local transportation planning and local land use planning in a way that a giant statewide utility is not going to be able to do. You can coordinate municipal policy generally with energy integrated.

David Hsu:

The first CCA in California, which is now called Marin Clean Energy, advertises on their website that they have solar panels on the airport parking garage, on the jail, on the landfill. These are ways a local utility can interact with transportation staff and urban planning staff; those are places that a utility would never look.

The city of Richmond actually bought a brownfield site from Chevron for $1; it had all these environmental liabilities, but they had the local development knowledge needed and knew through the city government that they could build it into a solar site. Richmond is a fairly industrial part of Contra Costa County; they put in a local jobs guarantee, and worked with local environmental organizations to build utility-scale solar according to all the green jobs criteria we want to have.

David Roberts:

A municipal CCA could help integrate energy planning much more into local planning, but on the flip side, one thing that a big utility can do is regional and even cross-regional planning and transmission, which there is desperate need for. Do you lose some of that ability when you disaggregate into a bunch of local units?

David Hsu:

You can still regulate at the state level, like we do in all of our states. I had a student once who works for the California Public Utilities Commission, and she said to me “CCAs make my job so much harder – I have to look at 100 cities and towns engaged in this rather than just three big utilities.”

We already have plenty of independent system operators and regional transmission operators in these restructured states. This is essentially making utilities into solely wires companies that just deliver the power. At the same time, you're building up this local capacity where cities and towns can express preferences for power, then transmit those preferences to the wires companies that are delivering the power. They can advocate for this in statewide fora.

In most states, CCAs are subject to a lot of the same restrictions and constraints that the utilities are – for resource adequacy, for renewable portfolio standards.

I would be hard-pressed to think of a state where we're doing that cross-district planning really well. You can’t fault CCAs for not doing it well; no one else is doing it well.

David Roberts:

I just wonder if that will make it even harder. It is worth pointing out, though, that there are associations of CCAs, where a bunch of them get together to plan as a larger unit.

David Hsu:

A lot of them achieve investment-grade status, so they're able to sign long-term contracts and issue bonds. The biggest procurement of vanadium flow batteries and long duration storage is through a group of CCAs in California now. There are groups of CCAs in California that are engaged in building charging stations.

The groups of CCAs can do things because they’ve built up. First cities and towns got together and formed a joint powers entity, which is like a separate authority outside the town’s balance sheets. They organize that way, and then the aggregations start organizing among themselves because they've already done this kind of planning.

David Roberts:

Do you feel comfortable making the generalization that CCAs and associations of CCAs are, on average, more innovative in these areas than utilities?

David Hsu:

I think that's fair. In California and Massachusetts, they're being more innovative than utilities. In Ohio, they're doing really interesting things with energy efficiency and gas aggregation.

In Illinois it's hard to say they've been more innovative, partly because the short-term nature of their cost advantages evaporated, and the three-year ballot referenda required to authorize a CCA is not long enough for a town to commit to building solar and wind. They have the ability to, they just haven't done it because there's too short an authorization.

David Roberts:

One sentiment I run across on CCAs is that if you want fundamental reform, you have to go full municipalization – you have to become a full utility and a CCA is like being half pregnant. Do you think that being generation-only is a real limitation in the long term?

David Hsu:

It depends if we see advantages in cities and towns owning their own distribution infrastructure. CCAs basically exist to take the procurement function away from the utilities, because the utilities have a local monopoly on distribution of power.

David Roberts:

But how will we see advantages when it's next to impossible to do? Boulder’s been at it how long now?

David Hsu:

Fifteen years at least.

I started the story with Scott Ridley coming up with this idea about aggregation, or renegotiating municipal franchises, because that's what he tried to help Chicago do. But he saw how hard municipalization was. Thirty years later, the mayor of Chicago and Commonwealth Edison, the utility there, are trying to renegotiate the franchise and the utility can essentially say “if you'd like our assets, you can pay us some wildly huge price for it. Those are nice ideas, but we may not take those ideas into account, or we might ignore them completely.”

The reason why CCA exists is because municipalization was seen as hard at the time. I think Scott realized that municipalization was always going to be too hard. The utilities have too much political power.

David Roberts:

In that sense, it's great in that it uncorked the dam a little bit and got things moving. I just wonder how far you can get on this model.

David Hsu:

I'm surprised by the antipathy a lot of energy analysts naturally have toward CCA, because it's a new thing. I don't think it's because people don't like innovation and new things in the energy system, but it does call into question the model that we've had for more than 100 years. I’m not saying we should disrupt the system for the sake of disrupting it …

David Roberts:

The current system is pretty garbage. There's a reason everyone hates utilities. There's a reason decarbonization is going slower than it should. I don't know that you'll find anybody who says “yeah, we've nailed it” about the system as it exists.

David Hsu:

That’s the thing. You don’t find utility defenders, but people look at CCA as this uncontrollable kudzu, as you say, which is growing rapidly. We don't understand the local wrinkles of all these things, and I think that's okay. My research convinced me that we shouldn't expect something as big as the energy system to be totally understandable. We can’t model and quantify it everywhere; I think that's why some system modelers are against it.

We need to adjust the energy system to reflect local circumstances. We know it has to work together technically; we love our alternating currents and interconnections and everything. At the same time, we need to have an energy system where people have some ability to make local choices, and, frankly, make local mistakes. You don't really have innovation without people trying stuff out locally. Some stuff is going to work in California that’s not going to work in Ohio, and vice versa.

The moderate skepticism in some ways is simply saying ”do we really believe local governments can be as effective as utilities procuring energy?” It turns out, they can be. We have plenty of evidence that public power is cheaper and more reliable. I’m not saying that I’m a diehard public power advocate, I just think that taking this half step is not as scary as it seems to some people.

David Roberts:

The current system is terrible for a number of reasons. I normally hate disruption discourse, but for god's sake, if any industry in the world needs to be disrupted it is monopoly utilities.

My cynical worry is that all of these local areas are arbitraging cheaper power opportunities that are eventually going to go away, and then they'll just go back to their utilities, and we'll be back where we were to begin with. I want to know what, if any, structural, lasting reform might come out of all this disruption.

David Hsu:

I walk around my neighborhood and I see signs that say “I'm a proud customer of Arlington Community Electricity. Ask me about it!” That's a level of education and organizing that didn't exist before. Energy managers in lots of cities are talking about what you can do with this.

There's no reason to think CCAs have a lasting price advantage, but there's no reason to think they have a lasting price disadvantage. And the cost of these energy managers and this organizing and awareness-raising among communities is fairly incremental. Basically, you're paying a utility to earn a profit on your procurement and delivery, so a nonprofit is going to have that margin already. The fact that you have energy managers and communities talking about it is a one-way good development.

Clearly, in Illinois, 50 percent of the cities and towns got out when the price advantage disappeared – but 50 percent stuck in it. It doesn't track totally with education and wealth, indicators of environmental attitudes, but those things are probably factors in CCA choices being stickier than we think. Once people have those choices, or once they express they want to buy cleaner power, those options stick around. Utilities have a competitor they have to meet, and that competitor is, as FDR called it, the public yardstick for private utilities. We need some competition first to even measure how utilities are doing their job.

David Roberts:

Michael Picker, the head of the California Public Utilities Commission, is notoriously skeptical of CCAs, and his whole point is that we need central planning of the electricity system. Do you think state legislatures, by virtue of having the power they have, are capable of doing that even in the presence of CCAs? Is that a worry at all for you?

David Hsu:

I don't look at CCAs as the problem or solution there. Almost everything about our infrastructure is federalized in the way our political system is. The US is a big enough country that we have state energy policies; even our states are so big that we need to have different large service territories. PG&E can't even manage their giant service territory to avoid wildfires. San Francisco has had a fairly poisonous relationship with PG&E and has been trying to buy their transmission and distribution assets for arguably, on and off, the last 100 years.

What works in San Francisco is not what's going to work in places like Paradise. It's not what's going to work in places like Marin County. We need to have some mechanism for local communities to express “here are the things we need to do in our community.” We need to get people engaged.

That's not to say we don't need larger central coordinating mechanisms. It's just that we all have even more skepticism that investor-owned utilities and public utility commissions, the way they've been constituted, are going to perform that central planning function either. That’s why the legislature steps in occasionally to try to do energy reforms in all these different states.

We do need better coordination, but is that coordination going to happen through a market? It’s going to happen through command and control, it's going to happen through technological standards – there are lots of different ways for us to think about centralized planning. Centralized planning physically is going to get down to engineers saying, “okay, let’s wield power there, let’s wield power there, let’s balance it here.” That's physically what has to happen in the grid at some point.

Also, we're starting to enter an era where we think a lot of these decisions are too fast to be made by people. We're going to try to automate parts of this. We're going to try to federalize some of these decisions to lower levels.

CCAs are a way to bring some measure of local accountability control in a way that makes sense to most people, through the local government, because they already have a relationship with a local government. That makes sense to me at that level. I'm not saying CCAs are going to help us solve that whole central planning problem at larger levels, which, honestly, we are still trying to figure out.

David Roberts:

The electricity system is such a fascinating conceptual problem – what's the right mix of centralized constraint and local freedom of movement to get the best outcomes? It seems that through CCAs we're having a not-entirely-rational-or-planned experiment in that.

I want to emphasize one more time that CCAs now have become a very large force that is shaping the electricity system in pretty fundamental ways, and it basically grew out of a dude with an idea. Which is just to say: if you have an idea, it could be the next one. Like Margaret Mead’s quote – a small group of dedicated people can still have powerful effects, even on a system that appears this large and bureaucratized and faceless.

Have you given any thought to what might be the next conceptual evolution of CCAs, the idea that might unlock the next level of change? Where's it headed?

David Hsu:

That is a good question that I have to admit I have not thought about. Part of the attraction of reading and learning about CCAs is how many different directions they're going in. It makes it hard to get our arms around what's happening. The sheer diversity of things happening among CCAs I find incredibly exciting.

In terms of structural evolution, they're still at the point where they have to overcome our moderate skepticism of whether they are adding value at that level. If they are going to make changes that we can recognize at a larger level, structurally, that's going to require CCAs organizing differently, or utilities vacating some space that somebody can step into.

That's where a lot of our conversation is. We have this utility model: can we judiciously pare back parts of it, like demand response? Are we able to put more decision-making in the hands of people that make the system work better? Demand response is one way of giving people different signals. Performance-based rate making has been called many things, but that might take away or change the incentives for utilities to act in a certain way.

Right now, utilities occupy most of the system. To have structural change, we’re going to have to pare back parts of their responsibilities to find innovation, because utilities personally aren’t going to do it. I used to work for a municipally owned utility, and it was a great place to work, but I never thought of investor-owned utilities as companies that were going to show us a lot of innovation. In order for others to innovate, we have to say to utilities “you either have to let somebody else try this, or put power onto your system, or interact with your system in different ways.”

David Roberts:

You can see CCAs growing and growing; at a certain point, utilities start losing so many of their customers that it’s going to force the issue. Crisis is probably not the best way to enter a phase of reform, but it's not something they can put off forever.

David Hsu:

At the same time, we shouldn’t think of CCAs precipitating crisis, because utilities don't make a lot of money from power procurement. They make most of their money from delivery. In lots of places utilities fight actively against CCAs, but not because they're giving up a major cost or revenue center; they're fighting because they're afraid that a new kind of competitor is going to show up that will be more responsive than they are through public utility commissions.

David Roberts:

Fear or competition is true for every giant incumbent industry, I suppose.

David Hsu:

But they could stay wireless companies and be fine. They probably make most of their money as wireless companies, and then they can focus on delivering power and not starting wildfires.

David Roberts:

That'd be nice. David Hsu, thank you so much for coming on and telling the rare happy story in these dark times.

David Hsu:

Thank you for asking. I appreciate it.

Share this post