Welcome back to Transmission Week here at Volts!

In my previous post, I explained why the US needs lots of new high-voltage power lines. They will help stitch together America’s balkanized grids, connect remote renewable energy to urban load centers, prepare the country for the coming wave of electrification, and relieve grid congestion. And oh yeah — we won’t be able to decarbonize the country without them.

Nonetheless, they are not getting built! It’s a problem.

Today, we’re going to walk step by step through the process and show why they’re not getting built. At each stage, we’ll look at what Congress can do — and what Biden can do without Congress’ help — to get the process moving. This is some wonky stuff, but I’ve tried to keep it as simple as possible.

Before we start …

Transmission-related acronyms

This post will involve numerous acronyms, so to make things easier, I’ve put together a little acronym guide here at the beginning for you to check as needed. If you’re already an electricity system wonk, you can skip this.

DOE: The Department of Energy. The federal agency responsible for, among many other things, energy research.

FERC: The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The federal agency that regulates interstate transmission of, and bulk sale of, electricity and natural gas.

IOU: Investor-owned utility. Privately owned companies acting as public utilities. Excepting some federally owned and municipal utilities, most utilities in the US are IOUs.

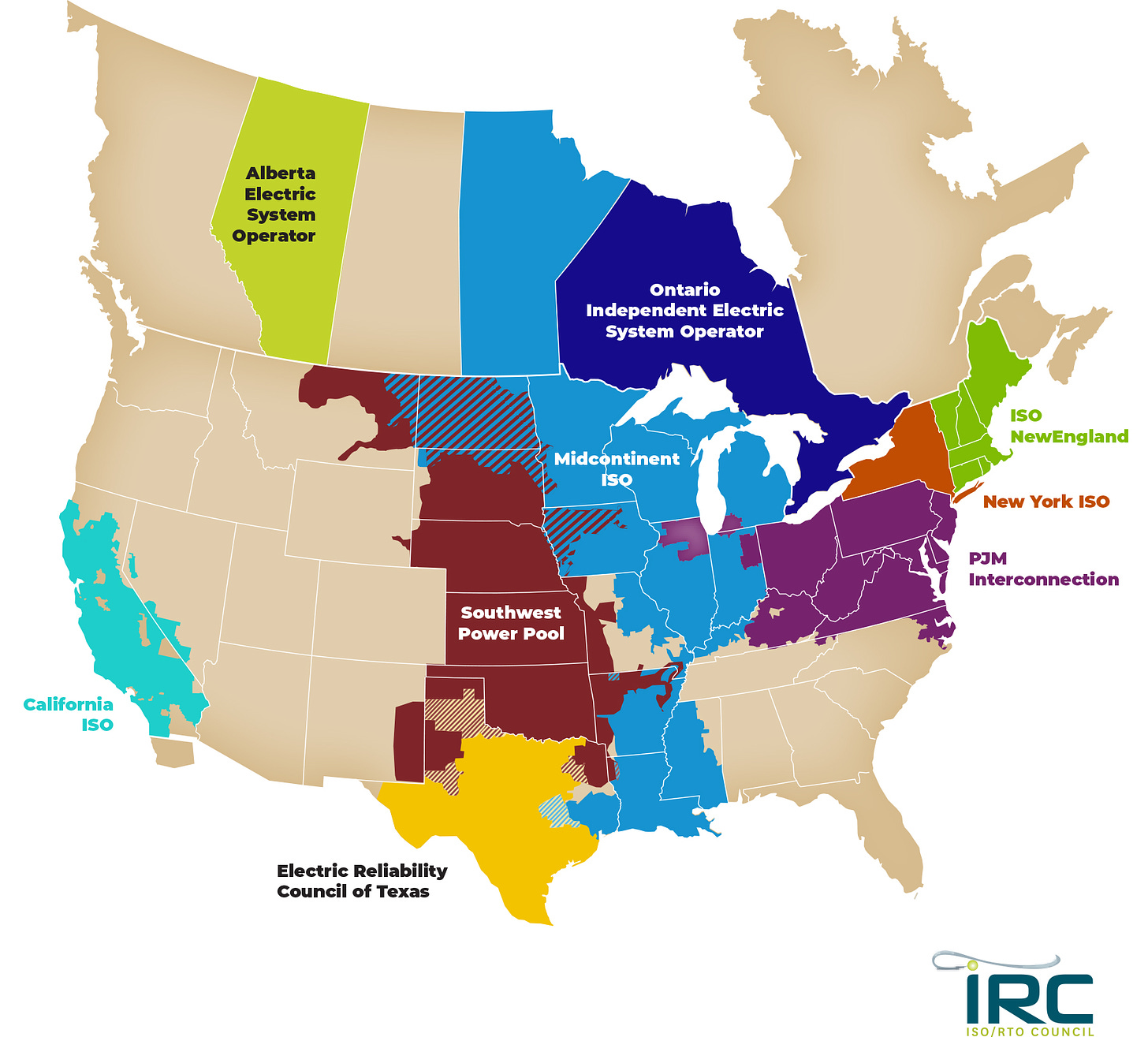

ISO: Independent System Operator. For our purposes here, you can think of these as the same as RTOs (see below). This is why you constantly hear people in this field using the unwieldy phrase “RTOs and ISOs.”

NIETC: A National Interest Electric Transmission Corridor, designated by DOE as an area in particular need of new transmission to ease costs or congestion.

NREL: The National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a DOE-run research lab.

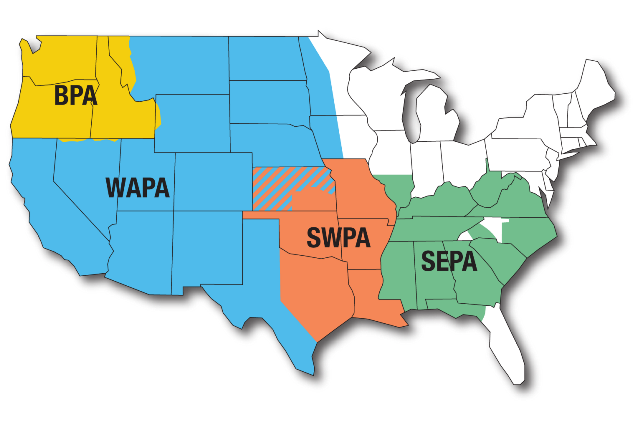

PMA: Power Marketing Administration. Federal agencies that operate electric systems and sell the electrical output of federally owned hydroelectric dams in 33 states. They are: Bonneville Power Administration (BPA), Western Area Power Administration (WAPA), Southeastern Power Administration (SEPA), and Southwestern Power Administration (SWPA).

RTO: Regional Transmission Organization. Non-governmental organizations (which nonetheless have government-like powers) that oversee transmission planning and wholesale energy markets in areas of the country that have been “restructured,” i.e., where generation, transmission, and distribution are owned by separate utilities. RTO membership is composed of the utilities in a particular region.

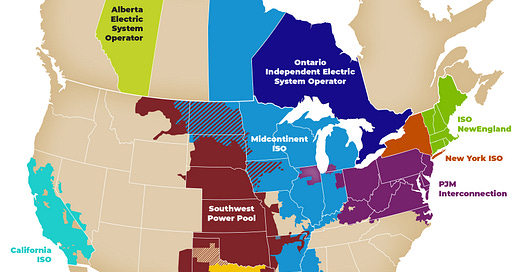

Here are the US RTOs and ISOs: CAISO, ERCOT, SPP, MISO, PJM, NYISO, and ISO-NE.

All right, let’s get to it!

There’s still not much inter-regional (much less national) transmission planning

For most of the history of the US electricity system, up to the 1990s, almost all utilities were “vertically integrated,” meaning they owned the whole electricity value chain in a given territory, from generators to transmission and distribution. They built large central-station power plants close by to population centers and then ran transmission lines out to them. There was neither much need nor much appetite for building longer regional or inter-regional lines.

Over all that time, states developed a persistently parochial lens and tight control over transmission planning.

Two things have changed in recent decades.

One, renewable energy expanded rapidly and got really cheap, which is why solar and wind are the fastest growing sources of new electricity capacity. However, as we saw in the previous post, the most intense sun and wind in the US are distant from population centers. This suggests the need for a wider scope of planning.

Two, a wave of reforms in the 1990s and 2000s led to “restructuring” in regions containing around half the nation’s electricity ratepayers. Vertically integrated utilities were broken up: generation owners were separated from transmission owners and both were separated from distribution-system operators (i.e., the local utility that sends you a power bill). Transmission planning in these restructured regions was given over to RTOs and ISOs.

This suggests there ought to be capacity for a wider scope of planning.

Indeed, FERC has acknowledged the need for larger-scale, regional and inter-regional transmission planning for decades, and attempted to make it happen through orders 888 (1996), 2000 (1999), 890 (2007), and 1000 (2011).

I won’t get into all those orders other than to note that order 2000 created RTOs (membership in which was voluntary for utilities) and was explicitly meant to encourage (though not mandate) broader regional transmission planning. Part of the idea was to create competitive regional markets for transmission, similar to wholesale markets for generation, in which merchant (non-utility) projects would compete on a level playing field with IOU projects.

As Ari Peskoe of the Harvard Electricity Law Initiative writes in a recent paper, “FERC was optimistic that [the IOUs’] central-planning development model would be replaced by ‘well-defined transmission rights and efficient price signals’ that would facilitate market-driven expansion.”

When it didn’t quite work out that way, once again, in order 1000, “FERC employed several mechanisms to pry control over regional transmission development from IOUs and break the IOU-by-IOU planning model,” Peskoe writes.

The general consensus is that, despite its best efforts, FERC has failed to bring IOUs to heel and produce truly regional transmission planning and markets. Local IOU transmission plans still serve as the foundation of regional planning. There is still virtually no transmission built through competitive bidding. In practice, IOUs still build virtually all the lines in and between their territories and have deliberately made it difficult for merchant projects to get sited and financed.

IOUs have engaged in a “shift away from regional projects, which must be developed competitively, to smaller or supposedly time-sensitive projects that IOUs build with little oversight and without competitive pressures,” Peskoe writes, and RTOs have implicitly or explicitly supported them in this shift.

These local IOU processes are often opaque, closed to journalists and public interest groups, but the broad shift is clear. Utilities in PJM, for instance, tripled spending on local transmission projects since order 1000 was issued. In MISO, spending on regional projects shrank from nearly $6 billion to just $300 million from 2014 to 2019. Not a single transmission project in NYISO has been built on the basis of regional benefits since FERC established the process in 2008.

A Brattle Group analysis found that between 2013 and 2017, 97 percent of the transmission approved by RTOs was not subject to a competitive process. Local transmission and reconstruction of aging facilities still receive the bulk of investment.

One problem is, IOUs are not mandated to be part of RTOs, so they can threaten to withdraw their assets from RTOs at any point. That gives them undue leverage; RTOs are loathe to cross them.

And so most transmission planning remains largely parochial. RTOs remain dominated by their members and predisposed to accept plans driven by local benefits. There are virtually no planning processes that take into account the changing energy mix or public purposes like integrating renewables and reducing greenhouse gases, and virtually no lines are being planned between regions.

What Biden can do

Biden’s FERC will start off with a 3-2 Republican majority. Current Democratic commissioner Richard Glick, a solid supporter of decarbonization, has been made head of the commission, and Democrat Allison Clements (who is also extraordinary) was sworn in in December.

In June, an additional vacancy will open up, which Biden will be able to fill, giving Democrats a majority, which will be significant on a commission increasingly issuing partisan split rulings on things like oil and gas pipelines and, er, the MOPR (don’t ask).

With a climate hawk majority, FERC could issue a stronger order mandating membership in RTOs and participation in regional planning. It could instruct RTOs and states to take into account the changing resource mix, the need for decarbonization, rising (and shifting) demand from electrification, and the benefits of inter-regional transmission. (MISO’s “multi-value project” process is often cited as a model here.)

FERC could also mandate that transmission planning take a broader view of reliability, resilience, and cost-effectiveness, to replace the siloed way they are assessed today.

It could also work with DOE and other agencies to develop a true national transmission plan, with an eye toward national policy goals, from which regional organizations could take their cue.

And, as Peskoe advocates, FERC could more closely scrutinize the local transmission planning processes now run — parochially and with very little supervision — by IOUs. Specifically, it could “reverse its longstanding policy of presuming that all transmission expenses are prudent, and replace it with a presumption that only capital expenditures committed pursuant to an independently administered planning process are presumed prudent.” In other words, shift the burden of proof to IOUs.

Doing so would push IOUs to put more transmission planning in independent hands. And FERC could take additional steps to force IOUs to regularly divulge key information necessary for independent planning.

“In transmission operations, separating ownership from operational control allowed the industry to capture benefits of both coordination and competition,” Peskoe writes. “Separating ownership from control over planning could have similarly significant benefits by untethering planning from maintaining any IOU’s state-granted advantages.”

One way or another, FERC has to wrestle control over transmission planning from IOUs and give it to independent organizations that can assess the full range of benefits.

What Congress can do

Congress could pass legislation clarifying that it intends for FERC to fully regionalize (and to some extent nationalize) transmission planning by taking the steps above. The Democrats’ Climate Leadership and Environmental Action for our Nation’s (CLEAN) Future Act, passed through the House last summer, contained language that would instruct FERC to issue a rulemaking to that effect.

Congress could also allocate funding to DOE to ramp up its research on a macrogrid, including resuming NREL’s Interconnections Seam Study. It could also fund DOE to assist state and regional organizations in studying and implementing inter-regional planning, and work out a transmission plan for offshore wind in the Northeast (which is currently beset by NIMBYs).

Basically, the federal government needs to study and develop best practices for inter-regional planning and then require that IOUs, RTOs, and states actually use them. Much of that legislative legwork has already been done in the Interregional Transmission Planning Improvement Act of 2019, introduced by Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.); it was included in the House-passed infrastructure bill, HR-2, but not in the year-end package that passed both houses.

All right, that’s planning! Up next is financing, but first, we need a cuteness break. Here’s my cute niece:

Financing transmission is unnecessarily difficult

The interconnection process — the process of connecting a new generator to the transmission network — is currently run by RTOs on a “participant funding” model, which means the project developer must pay for any grid upgrades or new lines required. This despite the fact that new lines create benefits (in reliability, efficiency, and regulatory compliance) that are spread state-wide, even regionally. A recent report from Americans for a Clean Energy Grid (ACEG) compared participant funding to “charging the next car to enter a congested highway for the cost of building a new lane.”

The process is currently a disaster. First, there’s the free-rider problem: no developer particularly wants to shoulder the costs for broadly distributed benefits. Second, no renewable energy project developer knows in advance whether their interconnection will require grid upgrades; when it does, they often drop out, which means the whole interconnection study and approval process starts all over again for the next project in the queue.

Third, it’s impossible to predict the location and size of power demand in five years, which is how long it takes to build transmission. And fourth, the one-at-a-time process foregoes opportunities to plan larger scale, multi-line regional projects.

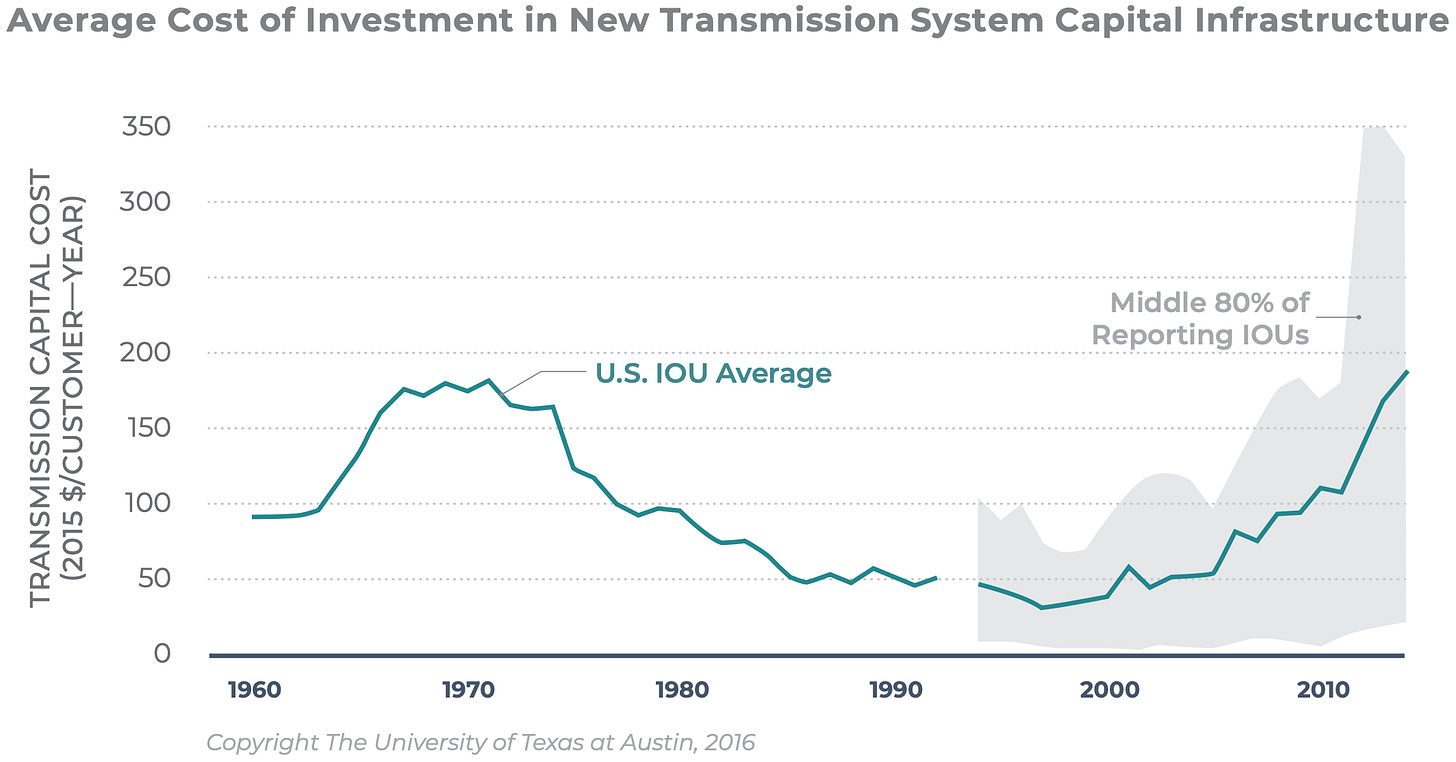

The financing barriers, coupled with the risk and uncertainty of a long, multi-stage regulatory process, serve to deter investment and keep costs unnecessarily high.

What Biden can do

What’s needed is for the costs of new transmission to be spread out more evenly among the beneficiaries, beyond the members of the particular RTO in which the line is proposed. That’s a highly technical undertaking in practice, so FERC could begin by soliciting solutions to this problem from RTOs and ISOs. But the process should result in a rule that forces cost-allocation reforms.

To speed things up, a FERC rule could also permit portfolio-based cost allocation, which allows RTOs to group projects together instead of running individual cost-allocation studies for each.

FERC could also apply more scrutiny and higher standards to local transmission investments, weighing them relative to regional projects that could provide the same benefits and more.

What Congress can do

Congress could pass legislation instructing FERC to prohibit the participant-funding model and spread costs out more equitably.

It could also implement tax incentives for transmission investment, along the lines of the tax credits for solar and wind. They could be tailored to encourage long-distance, inter-regional lines. (There are Democratic bills in both the House and Senate that contain provisions to this effect; ACEG has its own proposal. There’s a whole wonky post to be written about how best to design these credits, but I will spare you.)

And there are other ways Congress could pump money into transmission: investment grants, direct funding for inter-regional projects, support for states involved in regional and inter-regional planning, and money to compensate communities affected by new transmission projects.

The Department of Transportation issues what are called Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) loans, targeted at surface transportation infrastructure projects that are of regional or national significance. A similar loan program could be set up for transmission projects.

Finally, Congress could reinvigorate America’s Power Marketing Administrations (PMAs), which operate in 33 states (primarily to market and sell power from government-owned hydroelectric dams). As part of their operations, PMAs build and operate transmission. Congress could give them some money and a kick in the ass to get moving on more regional transmission.

OK, that’s financing. Onward to permitting and siting!

Permitting and siting are valleys of death for transmission

The Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP) at Columbia University and the Institute for Policy Integrity (IPI) recently put out a report (forthwith, the “CGEP report”) on what Biden can do to boost transmission without help from Congress. It serves as a good backgrounder on the barriers to siting transmission projects.

The key background condition is that the 1935 Federal Power Act gave FERC authority over transmission rates and facilities, but not over transmission siting. That authority remained, and remains, with states.

Consequently, a power line that runs through more than one state must be approved by each state’s public utility commission to act as a utility in that state. And it must secure a certificate of public convenience and necessity (CPCN) from each state siting authority. Notably, the report says, “state law often directs state commissions to consider only the interests of in-state residents and businesses” — in other words, the states that approve these projects are often prohibited from considering their broader benefits.

It is a difficult and unpredictable process, fraught with veto points. CGEP elaborates:

Several factors make long-distance transmission projects fragile to opposition—and there is always opposition. Their long length means that these projects inevitably encounter numerous stakeholders, potentially including federal, state, tribal, and local government agencies from which they must seek authorization, as well as private property owners from whom they must acquire property rights. And like all linear projects, they are subject to holdups, meaning that a single stakeholder can prevent assembly of a complete right-of-way.

Each state (in some cases, each county or even each landowner) has veto power over the project. Each is thinking about the benefits to itself and has no incentive to consider broader regional or national benefits. Endless lawsuits and delays drive up the cost of capital and drive away even the most determined financiers. It’s a virtually impassable set of barriers to long-distance transmission.

It is worth noting again that total state control over transmission permitting and siting stands in stark contrast to the way natural gas lines are permitted and sited in the US. The Natural Gas Act grants the federal government exclusive authority to permit and site interstate natural gas pipelines and the power to use eminent domain to acquire rights-of-way.

That streamlined federal approval process — especially the profligate way in which FERC has applied it under a Republican majority — has been a boon to natural gas pipeline developers. “FERC coordinates the process as a whole, has seldom rejected a pipeline proposal, and has generally managed to overcome state efforts to prevent pipeline development,” CGEP writes.

The situation is woefully inverted for interstate and inter-regional transmission projects, which can be blocked by any and every local interest and have no backstop federal authority.

What Biden can do

In section 216 of the Energy Policy Act of 2005, Congress granted FERC limited authority to site transmission projects within “National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors” (NIETCs) designated by DOE. If (and only if) a state has unfairly refused to permit a project within one of these corridors, FERC can step in and provide backstop permitting and siting authority, including eminent domain.

DOE’s initial effort to designate these corridors identified huge swathes of land, which freaked out local lawmakers and landowners. And the first attempts to exercise FERC’s siting authority were shot down by federal courts, leading many observers to speculate that the authority will never be used — and indeed, since then, it has remained notional. No new NIETCs have been designated or lines built on their basis.

The CGEP report argues that the authority still exists and that the specific rulings in the two court cases are not an insuperable barrier to action. Trump’s DOE issued a preliminary ruling in September saying that no new NIETCs are needed, but it relied on the Trump administration’s characteristically shoddy reasoning. Above all, it ignored future electricity demand.

The comment period on that ruling is still open; Biden’s DOE could revise the study to take in a broader interpretation of grid needs and constraints. It could quickly designate some NIETCs, to get the ball rolling, but it could be more deft about it by working with FERC to target designations narrowly, to support specific projects, reducing duplicative study and analysis and freaking out fewer landowners. It could even delegate to FERC the authority to designate NIETCs, as recommended by the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis and others.

And FERC could clarify its interpretation of its own backstop siting authority and when it plans to use it. Specifically, it could clarify that transmission projects that connect renewables to loads meet the criteria to receive a federal permit — and that it will take a dim view of other state-imposed obstacles.

Separately, section 1222 of the Energy Policy Act authorizes federal-private partnerships on transmission projects. In theory, writes CGEP, federal involvement “both frees the transmission project from the requirements of state siting and public utility laws and provides a basis for the exercise of federal eminent domain authority.”

This is another case where there have been very few attempts to use the authority. Biden’s DOE could deploy it by reinvigorating the PMAs, which could use section 1222 authority to build transmission anywhere it’s needed within their territories.

What Congress can do

All of this would be easier if Congress would pass legislation specifying the measures above: that DOE can delegate its authority over NIETCs to FERC, that access to renewables and future electrification should be criteria for designating NIETCs, that DOE and FERC should work together to create a single, streamlined federal permitting process, and that FERC has real backstop authority to site transmission within NIETCs.

Ideally, the federal exercise of eminent domain won’t be necessary. Congress could put money toward incentives for tribes, local governments, and states to revamp their permitting processes, perhaps accompanied by economic development grants, to ease the process.

“You really don't want to have to use the backstop siting authority,” says Fatima Ahmad, senior counsel with the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. “You want to start by allowing the developer to develop good relationships with the community before they pitch the designation of the corridor, then you want to have some kind of economic incentives for the communities, and then the federal government can use its convening authority to bring the states together to work something out. So [eminent domain] really is a last resort.”

In that same vein, Congress could put some money toward states and regional planners that are working to streamline siting. Money always helps move things along.

Drawing some conclusions

All right! This has been a long, wonky journey, friends, and I appreciate and respect those of you who made it this far. Let’s try to sum things up.

The basic problem with transmission is that we need a lot more of it in the US if we want to electrify and decarbonize, but it remains prohibitively difficult and expensive to build. Mostly that’s because the process is dominated, at every stage, by narrow, parochial concerns. IOUs are looking inward, RTOs are looking inward, states are looking inward. The intense localism of the process produces dozens of opportunities for NIMBY opposition and few tools to overcome them.

Politically speaking, it would be vastly easier to solve these problems with some clear legislation from Congress. As discussed here on Volts many times, a big climate bill is almost certainly not going to pass as long as the filibuster is in place. But that leaves open the possibility that some of this policy could sneak its way either into a budget reconciliation bill or one of the must-pass end-of-year funding bills.

There’s some precedent for these kinds of reforms getting bipartisan support — a few were tucked away in the energy bill that was tucked away in the spending bill that just passed Congress a few weeks ago — so there’s some hope.

But in the meantime, as I keep saying, Biden should use the powers of the executive branch aggressively. He should push the agencies to ease financing barriers, designate more corridors, permit more projects, and throw a little weight around on siting.

These reforms are somewhat obscure and technical, but there is nothing obscure about the jobs new transmission would create or the enormous economic, social, and environmental benefits it would generate. It’s right in Biden’s wheelhouse — he should go for it.

Coming up next in Transmission Week(s)

Remember how I said there would be four posts in Transmission Week? Turns out that was a lie. There are going to be five, and there might be two Transmission Weeks. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

In my next post — shorter, easier, and more fun than this one, I promise! — I’ll have a look at two clever ideas for how to build a national transmission grid without the siting hassles. I don’t want to get all clickbaity on you, but … it will involve both trains and lasers.

See you then!

Share this post