Here’s a question: is it better to drive somewhere or to take a ride-hailing service like Uber or Lyft?

I don’t mean better for you personally — faster or cheaper. I mean better for the world, for society, for the air and atmosphere … better, all things considered.

A clever new study from researchers at Carnegie Mellon University attempts to answer that question.

Ride-hailing services carry more external costs than private vehicles

In the paper, Jacob Ward, Jeremy Michalek, and Constantine Samaras attempt to tally up the relative costs to the environment and society of taking a trip via a privately owned vehicle vs. taking the same trip in what they call a transportation network company (TNC) like Uber or Lyft, in six of the companies’ biggest markets.

This involves two steps in each market. First, they add up how many miles the respective vehicles travel per trip. Then, they add up the total externalities — in vehicle emissions, congestion, crashes, and noise — represented by each mile traveled. (These externalities, notoriously, are not priced into transportation decisions; thus the name.)

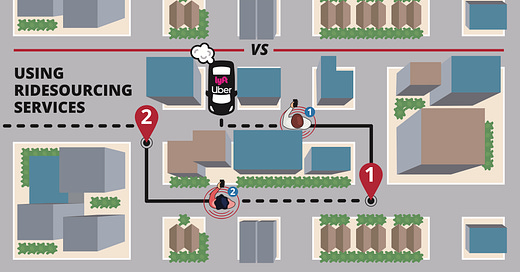

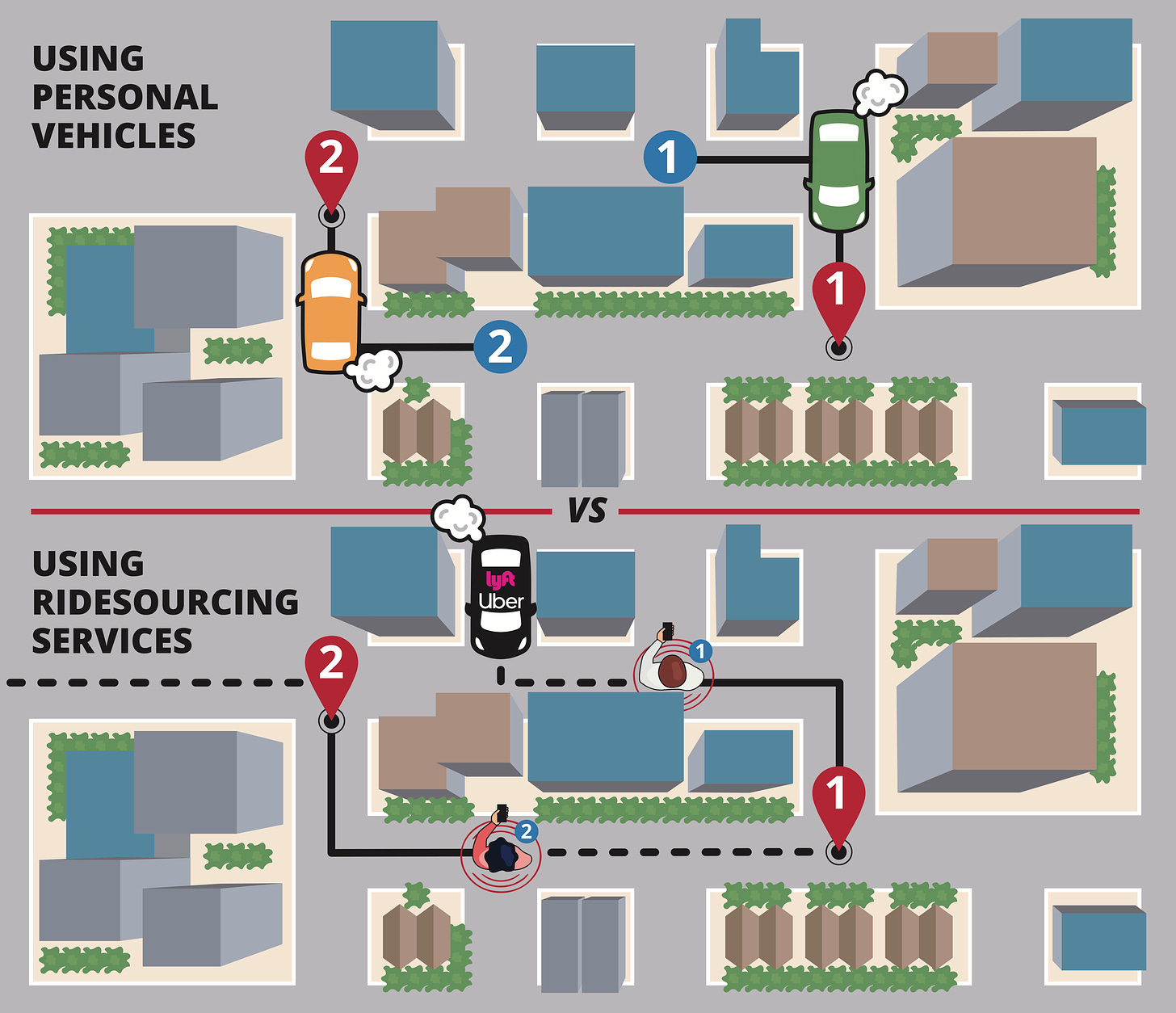

To understand the results, you have to understand one key fact: TNC vehicles travel more miles per trip. They have to drive between where they drop off one fare and pick up another, which sometimes involves quite a bit of just wandering around. This time spent with no passenger is called “deadheading,” and those miles must be added to their trip miles.

Here’s a clear visual representation:

Those dotted black lines on the bottom half? That’s deadheading.

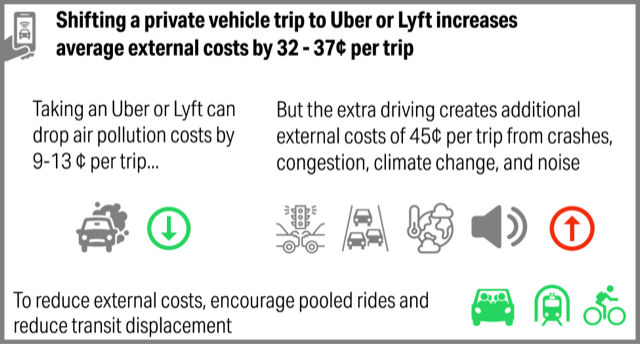

Those extra miles traveled represent more externalities — more cost to the environment and society. On average, a TNC trip carries 32 to 37 cents more in external costs than a private vehicle trip. (See also this recent MIT study, which found that TNC vehicles increase urban road congestion.)

There are three countervailing factors, but only the third is big enough to flip the equation enough to give TNCs the advantage in some limited circumstances.

Ride-hailing services reduce air pollution

First, though additional miles lead to more greenhouse gas emissions, congestion, crashes, and noise, somewhat counterintuitively, they lead to less air pollution. The secret here is that the bulk of particulate air pollution is generated from “cold starts,” i.e., engines turning over to start up. By contrast, TNC vehicles arrive “hot.” Their engines are already running, so they don’t do cold starts. In addition, TNC vehicles are, on average, newer, and thus cleaner.

On average, TNC trips represent a 50 to 60 percent decline (9–13¢ per trip) in air pollutants like NOx, PM2.5, and VOCs.

If TNC vehicles electrify faster than private vehicles, that advantage will grow, because EVs generate no tailpipe pollution. But if private vehicles electrify equally fast, the comparative advantage will stay the same.

Regardless, the difference is not enough to overcome the other externalities. TNC trips represent a 20 percent increase in costs from greenhouse gas emissions and a 60 percent increase in costs from congestion, crashes, and noise (all told, about 45¢ more per trip).

Overall, a 9–13¢ decrease and a 45¢ increase add up to 32 to 37 cents more per trip, on average.

Electric ride-hailing vehicles … are still mostly worse than private vehicles

The second countervailing factor is vehicle electrification. Doesn’t that reduce externalities? What the researchers found is that a) if the TNC car is electric, while b) the private vehicle alternative is an internal combustion engine car, and c) the TNC car charges entirely with zero-carbon electricity, then the overall environmental and social costs of a TNC trip and a personal vehicle trip are … about the same.

Of course, those conditions are rarely met. On real-world grids, which are still powered overwhelmingly by fossil fuels, electrification of TNCs reduces the relative advantage of personal vehicle trips by about 16 or 17 percent. It does not eliminate the advantage. And of course, that advantage will shrink as the private vehicle fleet electrifies.

So what, then, is the third countervailing factor, the one that can actually make a TNC trip better than a personal vehicle trip?

Shared ride-hailing vehicles are better than private vehicles

Maybe you’ve already guessed the answer: it’s ride-sharing. Put two people in the TNC car — i.e., have one TNC trip substitute for two personal vehicle trips — and voilà, you flip the script and your TNC trip is a net positive for the world. “When a TNC trip is known to be pooled,” the paper says, “shifting travel from a private vehicle reduces net external costs by a mean value of $0.60/trip.”

Wow, if you pooled three people you could save even more. Or four people. You could even pool dozens of people on large vehicles that travel on fixed routes and timetables. You could reduce all kinds of externalities! I wonder if anyone has tried that.

Speaking of which, what if the TNC trip displaced a trip on public transit, where the marginal cost in externalities of an additional passenger is effectively zero? What if it displaced a trip done via walking or biking, where the marginal externalities are, again, zero?

The study looked at that too: “When TNCs displace transit, walking, or biking, rather than personal vehicles, the increase in externalities is about three times larger (+$1.20/trip).”

What about avoided vehicle purchases?

You might think that, with the easy availability of TNCs, it might be possible for fewer people to buy cars, which would count on the positive side of the ledger.

However, there’s no such comfort. I asked the authors about this and it turns out they did another study (out on Jan. 6, d’oh) which found that the arrival of Uber and Lyft to a market tends to be correlated with a small increase in car ownership, especially in places where car ownership is already high and there’s not much population growth.

Via email, Michalek adds:

Even if Uber/Lyft do cause a reduction in vehicle ownership in some cities, I don’t think that alone would change our analysis about the costs and benefits of ridesourcing to society very much, because vehicle production emissions are a small part of overall lifecycle costs. The main costs come from driving.

What could change our results is if Uber/Lyft enable travelers to walk and use transit more than they would have otherwise. This could be, for example, (1) because Uber/Lyft enable a traveler to get to a transit line (providing a first mile / last mile solution); (2) because Uber/Lyft can fill in gaps in transit services, allowing travelers to take the train out to a nightlife area and take an Uber home after the trains stop running; or (3) because not owning a vehicle forces the traveler to walk, carpool, and use transit more often than they would if they had a convenient personal car option.

Unfortunately, there’s not a ton of evidence for TNCs enabling more transit trips either. Reviewing the studies done to date on the impact of TNCs on transit, the paper concludes:

We also find no statistically significant average effect of TNC entry on fuel economy or transit use, but find evidence of heterogeneity in these effects across urban areas, including larger transit ridership reductions after TNC entry in areas with higher income and more childless households.

There’s no way to avoid the conclusion: in most places, in current circumstances, all things considered, it’s worse to take a TNC ride than to drive a private vehicle.

What all of this means

I hope the implications of this research are obvious: ban cars.

Ha ha, I’m kidding. Kind of. But Uber and Lyft aren’t helping anything. They’re making most things worse. Even if they electrify, they’re still mostly making things worse.

The most notable finding in this latest study is something we already knew: moving people out of private vehicles (whether they’re driving or not) into walking, biking, and public transit sharply reduces overall costs to society and the environment. The difference that shift makes swamps any differences between the types of private vehicles we choose.

The basic problem with cars — whether they’re private, TNCs, taxis, flying cars, underground cars, or autonomous Personal Air Land Vehicles (PAL-Vs) with 5G and lasers — is a simple matter of geometry: they take up lots of space.

You can not have thousands of people living close together, each with their own two-ton vehicle, without congestion, sprawl, noise, crashes, air pollution, climate change, and all the rest of the horrors cars bring. That’s true of big cities, but it’s also true of small towns. If everyone has their own vehicle, there’s going to be traffic congestion or sprawl or both.

The only way to tackle all of these externalities at once is to get people out of cars. Out of their own cars, out of the Ubers.

That means prioritizing multimodal transportation in infrastructure and spending decisions. Creating protected walking and biking corridors that connect across town. Reclaiming lanes and whole streets from cars and turning them over to transit or simply to neighborhood walking and gathering. Upzoning and increasing density, especially around transit stops. Subsidizing electric bikes. (Basically, doing what Barcelona and Paris are doing.)

Electrifying vehicles will help on climate change, especially as the grid gets cleaner, but it’s not a solution to cars. Fancy new kinds of cars, even if they fly or go through tunnels or run on unicorn farts, are not a solution. Apps are not a solution.

The only solution to the problem of cars is fewer cars. That should be the goal of policy — not just transportation policy, but land-use policy and urban policy and economic policy and climate policy. For those who care about the public good, Uber and Lyft are a distraction.

Share this post