In this episode, veteran journalist Brian Beutler waxes nostalgic about the past 20 years of political journalism and muses about its future.

I’ve known political journalist Brian Beutler for a long time. We met back in the late 2000s in DC, in the heady days leading up to Obama’s victory, and have kept in touch fitfully ever since.

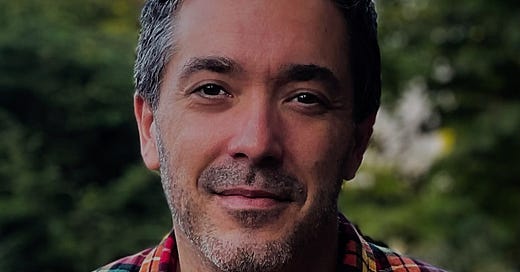

Brian, one of the smartest and most insightful political analysts writing today, has published in a wide variety of outlets, but this month he followed me into the wilderness — left his job at Crooked Media to launch his own newsletter, Off Message. He’s already written some great stuff and made some cool videos — check them out.

I figured I would take the occasion to catch up with him, wax nostalgic about politics past, discuss partisan journalism, and muse about how opponents of authoritarianism might show a little more vigor. Please enjoy this long and somewhat indulgent ramble down memory lane.

Text transcript:

David Roberts

So I'm sitting here with my good buddy Brian Beutler, who is a political journalist living in Washington, DC. He has been a political journalist for a long time. We've known each other for a long time, been involved in this mess of political journalism for a long time. He has worked, Brian, where all of you worked everywhere. The American Prospect, did you do that one?

Brian Beutler

I didn't do that one.

David Roberts

The New Republic.

Brian Beutler

Yes, I was there.

David Roberts

Did you do an American Progress stint?

Brian Beutler

No, you're misremembering. I was actually with you at Grist. I think I was on a freelance contract for like six months or a year way back in 2006.

David Roberts

Smokes, I forgot about that.

Brian Beutler

I worked at a bunch of places when I was like, a pup. So I think Raw Story still exists. First reporting gig. But I really got my training as a reporter at TPM. I was there for several years.

David Roberts

Right. That's the one I was trying to call to so spell it out for people. It's Josh Marshall's site.

Brian Beutler

Yeah, it used to be Talking Points Memo that's I think still the URL, but it's just TPM.

One of the longest standing, I mean, still going strong.

I rely on it all the time. I'm friends with my old editor there. He's still basically, like, running the day to day there, I think, the world of TPM. And then a very brief stint at Salon, which I enjoyed, but then The New Republic came and was like "join us instead." And so I said yes. And I did that through a really tumultuous period from like 2014, I think, to 2017. And then I was editor in chief at Crooked Media for six years, and now I am independent.

David Roberts

Yes, this is the occasion for the pod is my friend Brian has left Crooked Media and is now launching on his own, launching a newsletter because all the cool kids now have newsletters, a newsletter called Off Message where he is going to continue political journalism. You should all go sign up. I've learned an enormous amount from Brian over the years. And so I thought, on the occasion of Brian's birth as an indie, self-employed journalist, welcome to the fold, that we would sit down and catch up and I guess you could say, does the world really need two white, bearded, middle-aged guys of roughly similar socioeconomic backgrounds and ideological outlooks, affirming one another's priors for an hour?

Maybe not, but this is my pod, and if I want to have an indulgent episode periodically, that is my right as an independent. We got no bosses anymore, Brian to tell us not to do so.

Brian Beutler

My two favorite flavors are waxing nostalgic and vigorous agreement. And we're just going to —

David Roberts

We're going to get right into that.

Brian Beutler

Give your listeners all that.

David Roberts

All right. I feel like one of the signal characteristics of political journalism, and I expect this has probably always been true in all times and places is just that a lot of stuff happens, one thing after another happens, and it's a constant scramble. And so you can do it for a long time. And you really do not get many opportunities to sort of step back and think about kind of the arc of politics as you've experienced it over the course of a career. I guess what people used to do is report their whole lives and then become opinion columnists and write books.

But anyway, so one of the things I want to do is just think a little bit about kind of the arc of American politics that we've experienced and where that leaves you and kind of what you think about it and how you're thinking about politics has changed over experiencing all this. So you — when did you come to political consciousness as an adult, would you say?

Brian Beutler

It was definitely during the George W. Bush presidency, the first term of the George W. Bush presidency. And it was actually, like, less Bush vigor, although in hindsight, once I became politically awake, it kind of reverse incepted me how important it was. We've been on a wild ride since then. That was a moment when the Gingrich revolution could have been snuffed out, maybe, and normalish politics resumed.

David Roberts

My estimation of the importance of that episode has, as you say, risen steadily, more or less ever since, ever since it happened. And now I see it as sort of like the turning point in US. Politics, the pivot point.

Brian Beutler

So it was 9/11 and the Iraq war, and I went through a relatively quick transition as, like, an undergraduate from, like, "Holy crap, what's happening? Wait, we got to do something about this. Oh, George W. Bush is going to do something about it," to like, "wait, these seem like crazy ideas. What did Iraq have to do with that?" And by 2004, I was like, "this is nuts." And I voted for John Kerry that year. And I voted for Democrats ever since. And it was after that that I decided I want to go into journalism. But I knew I would end up being, like, a liberal journalist and that I'd have a really hard time just ignoring everything that had happened, you know, going on TV or writing in newspapers as if I wasn't aware that things had gotten so bad or gone so far off the rails.

David Roberts

But before this, did you have your callow, Libertarian high school, college period? Did you go through that?

Brian Beutler

Not really. I think I did vote for the Libertarian candidate in the 2000 election, but —

David Roberts

I voted for Nader. Confession time.

Brian Beutler

But I was in California. I came from a really reactionary part of California. I think the expectation for most people who graduated high school with me was that they'd vote for Republicans their whole lives, and that seemed like stuffy and distasteful to me, but also the Democrats, the Clintons, whatever. And so just like, protest vote Harry Brown, Libertarian candidate, 2000. But it was never like I'm sure I did some of the reading. The Libertarians love to do the reading and then talk about the reading, but I know it's never like, "Wow, Frederick Hayek was onto everything."

So it really was just like a quick transition from total political naivety to: the conservative movement in the United States has a really disturbing vision for the country, and blocking them from power has to be like priority one and kind of everything else falls beneath that and is shaped by that.

David Roberts

I entered the same way and this is something to do with our sort of micro generation. I mean, one of the things I sort of meant to mention is that I faffed about in grad school for a while, getting a philosophy degree after college. So by the time I sort of wound my way into journalism, I kind of slipstreamed into journalism right alongside your cohort, sort of you and Matt and Ezra and then the birth of the Netroots and all that stuff. One of the sort of interesting features of it is that I've always been about five to seven years older than most of the people I think of as my peers.

So, I'm like ahead of you guys in life stage. Like, I had kids while you guys were all still living in group houses and all this kind of stuff. So, I feel like I'm seeing your future. But anyway, you look younger than us though. Oh, well, thank you. That's because I kept the same hobby my whole life. But yeah, to me also getting involved in politics, the occasion was to look under the veneer of quote unquote, normal boring. This is what I indulged in in the 2000 election, back when I was really callow and really disconnected and not really paying attention, I sort of went for the whole, like, duopoly.

The parties are the same: "It's the system, man. It's the system that's broken. And who cares which face of the system you vote for, man." Voted for Nader based on all that horseshit. But pretty quickly watching 2000 and then watching 9/11 and watching Iraq, pretty quickly my whole posture was: under cloak of normal politics there's something rising on the right and it is ugly. And it is like there's an authoritarian, illiberal reactionary movement stirring beneath this facade of normality. And I need to be the town crier. I need to go out and bang on pots and pans and say, "look at this."

Like, look beneath the surface at what's happening. And so it's interesting for you and me both, preventing this rising reactionary movement from taking power has always been one and the same with our journalism and our engagement with political journalism.

Brian Beutler

I have a story about this, which is like, I think that if the Iraq war hadn't happened, or Bush v. Gore hadn't happened, or just things had been a little bit less extraordinary in the post 9/11 period, like, I was at Berkeley, I might have done the flip from 17-year-old pseudo-libertarian to what you were talking about a narrative progressive or socialist or something like that. Just because that was very much the milieu there still. But then 9/11 did happen, and then Iraq did happen and the imperative to try to knock Bush out of the White House was very high and the mistake of the 2000 election loomed really large.

It was 2003 probably, or 2004. There was a live debate at Berkeley between Christopher Hitchens and Mark Danner, who was a journalist. I haven't read anything by him in a long time, but he was at the New York Review of Books at the time and they were having an argument about the war, and that's what the debate was. And like, obviously Hitchens had his really signature flair and charisma and pithy everything, and Danner was this more studied professorial type and he was correct about the war, but that's not how debates work, right? And so Hitchens won.

But I was taken with the fact that's what they got to do with their lives. And I wanted to be able to do stuff like that. And I kind of wanted to bring Hitchens-esque persuasive abilities to the big moral issues of the day without being glib and wrong about them. And, like, everything since then, has just been kind of like the Iraq War. But it's some other extraordinary, reactionary, dangerous thing. It's Sarah Palin and the birthers or the effort to repeal Obamacare. It's just — it's just emergency after emergency after like, there's never a shortage of things to be passionate and right about in the hope of like —

David Roberts

Yes, if you want to rail against the machine, there's been no — plenty of machines to scream against. We have no shortage. Another thing about the 2000 election that I wanted to say is it's very paradigmatic in a bunch of different ways. But the main lesson I've taken from it and this is a lesson that I feel like I've learned again and again and again has sunk in deeper and deeper ever since then, which is when a time comes of political chaos, right? Everything's up in the air. Nobody knows exactly what's happening. There's a moment of high potential energy, right?

And no one knows which direction it's going to become kinetic, right? There's this sort of doubt and uncertainty. High potential energy in the air. You get these moments in politics periodically, and watching how the two sides dealt with that was so instructive because on the Democratic side, as you well recall immediately, it was, "How is history going to judge us as we do this? Right? What's the right thing for America. What's the fair thing to do? Let's meet in the middle. Let's be patient." Al Gore, whatever you think about him genuinely in that moment, had noble motives in mind, had history in mind and the larger welfare of the country in mind.

And they were basically the entire party was performing as though the entire episode were being overseen and judged by some sort of referee who was applying basic rules of accuracy and fairness. And basically like they were trying to please the teacher, trying to please the referee. And then on the other side, when chaos comes up and you've seen this happen a million times since then, no one on the right had a moment of doubt or hesitation or scratching their chin and pondering the judgment of history or pondering what's fair in the big picture. No one. No one on a blog, in a magazine, in politics, no one had that moment.

They all like a school of fish immediately recognized this is a moment of uncertainty and chaos. Chaos is a ladder. Let's fight, fight, fight, fight, with any tools necessary. Don't give a shit about consistency. Don't give a shit about fairness.

Brian Beutler

Act and then react, and then act again. And then react again.

David Roberts

Always push our interests, no matter what we said before, no matter what anybody else says, no matter what may be fair, blah, blah, blah. Just act on our interest. Push, push, fight, and then secure the victory. And then once you have the victory, then you have all the time in the world to come up with pleasing stories about why you did what you did and how it was all fair after all, and why we just need to move on and why we don't need to dwell on the past, et cetera, et cetera. Once the thing's over, then you can smooth it all out.

But when there's chaos, immediately go on the attack. And we've seen this like, this is the essence of the two parties ever since, really. And you could say the same thing about 9/11. You could say the same thing about Iraq. Just like when Iraq came up, as you say, there were all these people on the left sort of, like, ripping their hair out, like, "what about this? But what about that?" Doing the Hamlet, like, "maybe this, but maybe that. What's the bigger picture? What's history going to say?" And on the right, it was just like, "Here's a moment of chaos. Let's fight to advance our interests on every front at every moment." And that's just, like, the deepest lesson I have written on my psyche about U.S. Politics ever since then.

Brian Beutler

Yeah, and I mean, I'm going to pull a version of David Brooks and say, I think there's a happy medium in between. I like that. Democrats will survey the nation. What are the pressing needs facing the country? And not like they'll address them all perfectly right then and there, but at least they'll just be like, "oh, okay, the roads and bridges are bad. Let's rebuild them. New parents don't have enough money. Let's try to give them some money." And Republicans don't really engage in that kind of assessment, and they don't even think that the government should be doing that stuff.

And it's really hard to bring that analytical bench to things. If A, you're an ideologue and you think you're not supposed to do it in the first place, but B, if you're just saying like I have to say and do in the moment what is necessary to gain power, you're just going to be inconsistent all over the map all the time. And that's why Republican policy is always a bad fit for the moment, it seems like. But the flip side of it is — then you think, well, let's just compare records and which presidents have been better for job creation, which President Joe Biden or Donald Trump actually passed an infrastructure bill versus talked about Infrastructure Week all the time?

And Democrats own that game and nobody gives a shit because like you said, there's no referee.

David Roberts

Exactly. If there's a referee to be like, "I've tallied up your column, and your column Dems are out ahead on improving people's lives." There's just no one to do that.

Brian Beutler

Yes. And so that's why here we are in the year 2023, and Republicans are, like, crushing Democrats on who's better on the economy, and it makes no sense. And I bet you if you took a poll of the public and asked who's better on infrastructure, Republicans might win that one too. Or at least it would be like 50-50, but it should be 100 to zero, right? It's simple and it's not.

If evidence were involved in any way. But get back to the history a little bit because and tell me if this was your experience too. Sort of like 2004 was like the early first nadir for me because you and I both got sort of like activated against Bush during his first presidency for very obvious reasons. Reasons that in retrospect seem like he hasn't come out better with the passage of time. Like it all looks even worse than it was.

Yeah.

David Roberts

And then 2004 came, and that was the first time I remember an experience that would also be repeated several times over the years, which is me thinking, "well, this is obvious." I don't even really know how to mount an argument here. I just want to say, "look," I just want to hold my arm out and say, "look at all this." Case closed, right? And yet America goes and reelects him. And I was just flummoxed by that. Absolutely spun off my axis. But then after that, we started this arc of 2004 forward where Bush sort of fails on his Social Security drive and Dems win big in the House in 2006.

And then there's the rise of Obama and that race and all the hope around Obama and the election of Obama, that whole period from sort of 2004 to call it like 2009, let's say, let's give Obama one year of that. That was a period that, as I think back on it, if you're a younger person than us, as there are many out there, if you came into politics later, or if you came into politics around like 2010, say, you've never experienced a period like that where it actually felt like, "Oh, my God. The forces of decency are rallying. We're going to move forward again.

There's hope, things are sane. There's a guy in charge who is speaking in complete sentences and is clearly intelligent and is clearly a good person, a good father, a good husband." That whole period feels like a weird dream in retrospect, but it's a dream that people younger than us have never had any taste of. Like, if you came in in 2010, it's been all shit since then, wall to wall. At least for us. There is this weird, hazy memory of the idea that things could get better.

Brian Beutler

Yeah. So, I mean, to pick up where I left off in college in that Hitchens - Danner debate so it was like, "Okay, there should be really eloquent spokespeople, but not for the Iraq war, but against it." Right.

But that was a time when Democrats, they were not making a dent in that direction. Right. This was John Kerry reporting for duty. Right. Like, the young people won't get that allusion, but it was like a signal moment in Democratic politics prior to Obama. And it was the era when Democrats were, like, agonizing themselves over whether do we have a religion problem? Like, maybe we're not winning because we're not appealing to churchgoers.

David Roberts

Thinking that nominating a war hero would get you something from the other side. Right?

Brian Beutler

Yeah. The referees would say, "look, George W. Bush kind of a draft dodger. John Kerry. War hero. Case closed."

David Roberts

You're not allowed to call this guy a coward because he's a war hero. I'm blowing the whistle on that one. Where was that referee? It never showed up.

Brian Beutler

The swift voting actually left a lifelong impression on me because initially I was like, well, people are just going to be super offended that Republicans are tearing this guy down in this way, but A, they weren't, and B, I was also demoralized and put off and came to lose respect for Kerry and the Democrats for not standing up for themselves. Right.

David Roberts

And just like, waiting on the referee, right? Waiting on the referee is what they're doing.

Brian Beutler

And there is no dignity in that. And honestly, for all the things that you and I spend our time arguing with other people on the Internet about how to optimize politics or tweak policy in this or that way, to make polls move in whatever direction, is like, throw all that out and just act like you have some pride in yourself and will stand up for yourself when people smack you in the face. And a lot of your political problems are probably just going to go away.

David Roberts

Like you would if you were just a person.

Brian Beutler

Yes, be a person. I honestly wish I thought politics were a more elevated craft than this, but it's like, "how do you become popular in high school?" is a better question to ask yourself.

David Roberts

Not having good arguments.

Brian Beutler

Right. It's not having good arguments. It's not conducting polls and then going around to the people in high school and saying what the polls say they want to hear. And it's not like running for class president with an item list agenda. It's just like being chill. It's being a reasonable person, but also not a pushover.

David Roberts

And signaling strength in these sort of like, nonverbal —

Brian Beutler

And being comfortable in your own skin and just like, how do you — and life is like that too, but politics also. And John Kerry was flunking that test. He was like, you are acting like somebody Nelson Muntz would point and laugh at if you were in high school right now. And it left this lifelong impression on me and it's like at the core of my politics today. It's the basis of a lot of what I write about.

David Roberts

Yes, it's sort of the animating message of your writing in the past several years and I assume your new newsletter, which is the same. Like, you have the tripartite failure, right in that episode, right? As a one, you have the right being nastier than — no matter how cynical, you can never keep up. At the time, I was like, "God, that's just like, so gross. Grosser than that's so out of bounds. That's so obviously gross." So like, one, the right being grosser than you think they're going to be. Two, Democrats being passive in the face of it and trying to be dignified and not dignify it with an answer and not get in the mud and all this and wait for the referees to show up and save them.

And then three, the mainstream political press failing to convey that a Rubicon has been crossed, that something has gone out of bounds, that something is now not normal, that it's not normal for a political movement to mock a veteran's service. That's just not like — we are the kind of people who are outraged about that kind of thing, right? Like people just don't know. Average citizens don't know what's normal and what isn't. You know what I mean? They pick that stuff up through signals, through trusted people they know and through media. And if the media says like, "Oh, well, they're just mocking his war service and how's that going to affect his chances in November," then people are like, "Well, I guess that's a thing we do now. I guess that's how they roll now."

And that tripartite failure is basically the template over and over and over and over and over and over again ever since then. Reliably. You could go back to last week and find one if you did.

Brian Beutler

Totally.

David Roberts

I mean, pick a week.

Brian Beutler

Republicans are expelling Nancy Pelosi and Stenny Hoyer from their office in the Capitol to be — like, as retribution for not saving Kevin McCarthy's ass. And it's the same thing. It's like they're just smacking him in the face. Are they going to well, "It's so disappointing that they would do this" like, no. Stand up for yourself.

David Roberts

Yeah. And remember when the asshole, who was it, yelled "liar" at Obama during the State of the Union? Yeah, that episode also. I was, "Well, Jesus, that's so outrageous. It's so obviously outrageous." But again, it's only outrageous if people react as though it's outrageous, and if they just don't.

Brian Beutler

It was Joe Wilson, right?

David Roberts

Yes. And apparently that's just like, a thing we do now is, like, right wingers shout at the president.

Brian Beutler

Yeah, constantly. Now it's like the whole Republican conference instead of just —

David Roberts

I know. Back then, people will have to trust us, that that was really shocking and outrageous. But pick an episode. It's all that same basic framework.

Brian Beutler

Yes. This thing, stand up for yourself is like a big it underlies a lot of the work I've done over the last few years. It's one of the big reasons I launched Off Message. And another big reason is, like, the Netroots, I feel like arose in some way as a response to that kind of thing, if not that exact thing.

David Roberts

Yeah, right, exactly.

Brian Beutler

And my recollection of the Netroots is that it was premised on two things, right. Like, one, first and foremost, you got to crush the Republicans. But two, Democrats have proven so far to be really shitty at that.

And everyone in liberal politics, I recall, or most people in liberal politics anyway, they were cool with these two ideas, living side by side. And after Trump won, I kind of expected a revival of that kind of righteous ethic. Just like Democrats should be a little bit more confrontational with Republicans, especially when Republicans have power and if they don't, liberals, like the whole progressive ecosystem, et cetera, should feel unencumbered to criticize them for it without worrying that they're helping the Republicans in some way or not presenting a unified front against the right and Donald Trump and authoritarianism or whatever. But it didn't happen.

Like, the politics of over caution dominated in the four years of the Trump presidency.

David Roberts

Well, the immediate response to him winning was, "Oh, we weren't over cautious enough in the run up to this." Right. Like, that was the immediate —

Brian Beutler

When Democrats won the House back in the midterms in 2019, the first thing they did was, like, Chuck Schumer, Nancy Pelosi went to the White House. And, I mean, I realized this was a faint and it was meant to embarrass Trump, and so but they said, "Let's do a $2 trillion infrastructure bill together. You got them." It's like instead of everything we've seen the last two years is so unacceptable and accountability is here for you now. And look, the water is warm. If you decide you want to do anything good for the country, we're not going to say no.

But that's not our main mission here. Our main mission is to expose what you've been up to: the things you've been hiding from the public. That's all coming out now. You are in for the colonoscopy of a lifetime. And that was not the attitude. And it's not like I was shocked or anything. I was not like but I still don't understand the mindset that convinces a party and its leadership after suffering so much abuse from this guy that you're not going to do something about it when you win the power to do something about it.

David Roberts

What was it? Josh coined a term. Oh, right. He called it "bitch-slap politics". I think he has since revised this. I don't know if he has a new term for it. I think he's —

Brian Beutler

Whatever, I mean, it's fine. Bitch-slap politics. It conveys something real.

David Roberts

Yeah. It's like playground stuff. It's not a rational exchange of ideas. Just like if somebody comes up and smacks you and then people are standing around in a circle laughing and you start into a soliloquy about how unfair it is that they slapped you. Like, this is brainstem level stuff going on, you know? This is stuff that operates on a much deeper level than ideology.

Brian Beutler

The Paul Pelosi hammering to head — Okay. I had an argument with a friend who disagrees with me around that time because I thought, "well, this is something that Donald Trump is essentially responsible for and Democrats should talk about a lot now while everyone is still shocked and appalled by it." And Democrats, of course, did not really want to do that. And this argument was about whether they were right to pivot back to inflation or crime or whatever the thing happened to be. And I was like, do you honestly believe that if the shoe were on the other foot and some left-wing person or progressive person took a hammer to Elaine Chao's head now two months before the election, or whatever. Like, you would agree with me that the election would be over and Democrats would lose, right?

That would be the end of it. Because it would be the only thing that anyone talks about —

David Roberts

It creates a moment. Do you or do you not exploit that moment to advance your political interests? And basically right-wing media just is a giant machine built for that — explicitly that purpose. When a moment happens, bring all the guns, turn all the guns in one direction, dominate conversation with this one thing, and Democrats just don't want to do that. And this gets to my central question. This is the main thing I wanted to — there's no answer to this question, but I want to ask it anyway, because this is what haunts me and keeps me awake at night.

So I'm talking about that tripartite failure of, like, Republicans being grosser and nastier than anyone thought. Democrats still not fighting, not getting angry and fighting in response. And then the mainstream media mushing over it all with this sort of blanket of both sides mush that obscures responsibility and obscures consequences and obscures the sort of nature of it all, that those criticisms were all, as you say, alive and well in the Netroots in the early 2000s. This is what the Netroots came up to say. Like "Fight, for Christ's sake. Like, look at what's happening. This is crazy, what's happening around Iraq, and no one's out saying it.

Like, someone come out and say it." That was the impetus of the Netroots. And so basically, fast forward literally 20 years, Brian, 20 years, and all those critiques are exactly the same today as they were then, and all the behavior is more or less the same. And I used to think back when I started, like, these dynamics are happening under a veneer of normality, a veneer of normal politics. And my sort of job is to sort of strip the veneer and show you the dynamic beneath. Because assuming that if more people saw and recognized the dynamic beneath, then they would just naturally recoil and change things, buyt then, you know, you could cite a bunch of different episodes to make this point, but obviously the big one is Trump winning, right?

Trump comes along and there is no veneer, zero veneer. Not only no veneer, but he will actively destroy any veneer that his allies try to throw up, right? He will actively say "No, no, that's not the reason. It's just because I hate people and I'm cruel." He won't let you veneer him. And it's sort of like, true for Democratic weakness and it's true for the mainstream media's failures. It's all the same as it ever was. But there's no veneer left. So, like, what's my job now? I can't strip away the veneer. There's no veneer. The dynamics are sitting out there in the open, visible and obvious to the naked eye, and yet people are not recoiling and nothing is changing.

So what do you do now? This is my existential, basically since, like, 2015 forward, this is my sort of existential crisis. Like, if America can see directly and obviously this dynamic and it doesn't seem to mind it, it's not recoiling, right? There's no backlash. Then what do I do then? Maybe this just isn't the country I thought it was. Literally, what's my goal now? Does that resonate?

Brian Beutler

Yeah, no, I think I do have an answer to this question, and I don't even think it's that complicated. The only addendum I'd make to what you just said is that it's 20 years later. I actually think that the positive effect that The Netroots had on Democratic politics from 2006 to 2008 or whatever it was that's kind of gone.

David Roberts

It got shut down. Right. It got shut down by the establishment.

Brian Beutler

And it was and absorbed in some cases, by the establishment too. And the absence of it, I think, is very strongly felt because there isn't a loud chorus of liberal voices who are willing to be a little bit iconoclastic and not worry about presenting a progressive movement in disarray or a liberal movement in disarray and aren't worried about what the various congressional offices will think of them. And just say, we don't think that you, the Democrats, are running an optimal opposition strategy to this threat. I think that the truth is that the Iraq war era also had very little veneer.

I mean, George W. Bush was a more polished person, and he well, I.

David Roberts

Think about, like, Dick Cheney. Like, Dick Cheney is the essence of the guy who is an absolute monster in a suit, talking calmly, making you feel just like, oh, this is a calm guy who knows exactly what's going on.

Brian Beutler

When I say the word torture, I bet you a single image comes to your head and it's the guy standing on the thing with the hood over his head in crucifix position. There was no veneer there. That was politics in 2005, and it was awful, and the Netroots was like, "Democrats point at that and call it awful, and if you don't, why are we here to help you? If you can't help yourself, what do you want from us?" Right? I think that that was very healthy, and it doesn't really exist anymore.

David Roberts

Well, it seems like what happened is that when Trump won, it kind of threw everybody a little bit off their axis.

Brian Beutler

Yeah, for sure.

David Roberts

And it's just the danger of Democrats losing again has become so acute and existential that everyone's terrified into tiptoeing.

Brian Beutler

I don't think it's like corrupt forces or capture. There's some level of capture there, but it's risk aversion. It's fear, and it's totally well grounded. It is scary, right?

David Roberts

It's fucking scary.

Brian Beutler

I don't begrudge the people who get frustrated with me for focusing a lot on Democrats in my writing and criticizing or in many cases, praising the way they respond to things instead of attacking the Republicans, because, as you say, what's the point? We all agree. It's all out there in the open. There's nothing more I can do than just be like, "See? It's bad."

David Roberts

The guy's mocking injured veterans. He's saying, "I find injured veterans distasteful, and I don't want them around me." Like, that's, just like, I don't know how to argue that that's gross. How would you even argue that that's gross? It just is viscerally on its face repugnant. So what do you even say about it?

Brian Beutler

I mean, when Trump won, I think in a weird way, the political world was a little bit lucky that he also won the House and Senate. I mean, like that led to bad things too, but Democrats were completely locked out of power. And so really all there was was just, like, taking stock of what this horrendous formation was doing with their power. And also like, "oh, look at the information that's coming out about Trump" and his business ties and the Russia stuff. And so for that two-year period, that's what I was writing about. And also to the extent that I thought media wasn't conveying the gravity of the situation well enough, there was an element of media criticism in there, but the Republicans ran everything.

And so that was the focus. It was when Democrats won back the House in 2018, but then much more acutely when Joe Biden beat Donald Trump that it's like, okay, we're still in this twilight struggle against authoritarianism. It's still extremely important that Democrats do their opposition politics well, but now they're the ones with the power, or at least they have more power institutionally in Washington than Republicans. What are they going to do with it, and how are they going to exploit it to weaken the opposition so that they stand a better chance of defeating them in the next election?

So that means you're writing a lot about Democrats, you're doing a lot of in-house critique. And I think it's like the answer to the riddle you pose like, what do we do to try to effectuate positive change or better politics or whatever it is when Republicans are so naked, is to be willing to look in-house and see how things are going. And if you think that Democrats are inexplicably letting an opportunity to exploit pass them by, you can just pound the table about it. And, I mean, it's not as intellectually exciting as writing about policy, which is interesting, it's like puzzle solving, but it's real —

David Roberts

There was, like, a few years we got to do that, these brief little lacuna in our careers where we actually were just for a year, policy mattered just for a blink of an eye. I enjoyed those times immensely.

Brian Beutler

Me too.

David Roberts

What about this idea? The big fight these days is — on the left, there's this faction of people more or less singing your song, which is just "quit trying to act like this is normal, quit trying to be normal in the face of this. Convey that it's outrageous. Convey that it's out of bounds. Attack, fight. Like do politics. Brand yourselves as good and brand your opponents as bad."

Brian Beutler

Crazy.

David Roberts

I know, right? Brand the Republican Party as bad. Rather than anytime you mention the Republican Party, it being in the context of how much you can't wait to work with them on bipartisan this and that, right? So just there's a faction of people out there who saying this and have been saying this for many, many years, and then there's a sort of faction, you know, that's like "actually what America wants from Biden is that he's normal." He's not Trump. He's not crazy. He's not fighting all the time. There's not all this fighting. He should in fact, be more normal, make more gestures, know sort of centrist positions.

You know how, like Obama used to sort of make concessions to border security and he used to make concessions he used to make concessions to his opponent's arguments and try to find this centrist road forward and this would pull in more swing voters. Basically the opposite of what you're saying. And there are nuances on all sides of this. But what do you think about that basic argument that what wins for Democrats is being kitchen table focused normies who understand your reactionary impulses and will acknowledge them and not going to criticize you for them, but we're going to try to gently nudge things forward a little bit.

What do you think about that basic argument?

Brian Beutler

So I don't think that the insights or the beliefs at the core of those two visions are totally incompatible. I think that you could, in theory, have a very muscular confrontational politics that was run by a party that had a very moderate policy agenda.

David Roberts

I do want to put an exclamation point on that. This is something I feel like needs to be better understood in some respects those two axes, the sort of lefty versus centrist policy axis and then there's the sort of pugnacious versus accommodating axis, fighting versus not fighting axis. And to some extent those are orthogonal. Like you could come out in different places on those.

Brian Beutler

Absolutely. What do I really think is that if Democrats were trying to be 100% optimal, like right on the top of the curve of what maximizes their chances of winning elections, I think it would probably be some version of confrontational pugilistic, pugnacious you said, politics and like, you know, being chill about policy, not trying to be too radical or whatever, but it just seems very strange and wrongheaded to me to focus on perfecting the policy appeal when the party leaders aren't doing the pugnacious thing right. That's where the untapped potential really is. Any additional margin you can get by adjusting your child tax credit to be just so is like tiny compared to that.

And so my main beef with the people who say Joe Biden should be more centristy, more moderate in his policy and know, accommodating to Republicans is like, it just makes me want to pull my hair out. But how do you think your hypothetical medium voter comes to the conclusion that a particular politician is moderate or not?

David Roberts

Is it analyzing policy positions on their website?

Brian Beutler

These are mostly policy issues that Republicans weigh in on, but yes, I guess abortion, the big moral policy questions of the day. Republicans could gain a big electoral advantage, I think, by saying "we're no longer forced birth people," right? And "we no longer want to abolish Medicare," that would help them. I don't deny that. But I don't think that —

David Roberts

I almost wonder if it would. I mean, this is the thing. This is the whole of our past 20 years is always thinking that there's some threshold right? There's something that could happen that would snap us out of this horrendous equilibrium. Presumably, there's something extreme or obvious enough on one side or the other that it would break us out of this 50-50 balance. But all I've seen over the past 20 years is things that I think will do it, not doing it, and Trump didn't do it. So would that even make that big of a I find myself just kind of speechless.

I don't know what would change public opinion at this point. If Republicans have not been grotesque, if the public is still saying on polls that the Democratic Party is more extreme than the Republican Party, like a year after the Republican Party tried to coup! Literally what could break us out of that equilibrium? Like, if they flip-flopped on abortion, would that do it? I don't know. If Trump literally shot someone on Fifth Avenue, would that do it? I don't know. It's at this point difficult for me to even imagine what could break us out of this frozen 50-50 horrendous equilibrium.

Brian Beutler

The institutions and incentives aren't set up for it. But if Republicans could clean slate themselves from Trump and the last 40 years of their politics and become like kind of Christian social —

David Roberts

A European center-right party.

Brian Beutler

Yeah, I think that they would win elections by huge margins in the United States.

David Roberts

Do you? I wonder about that because I've really come to think that in politics, having a truly furious, activated, well-funded, well-organized minority is better for you than having a sort of majority that's vaguely on your side. I almost feel like having this army of cultish zealots, you know, has advantages for the Republican Party that don't necessarily show up in voting totals. You know what? Like just in clean energy that I cover in wind energy, like they're out organizing opposition to wind energy on the ground in a way that absolutely just dwarfs anything that the left is doing.

And you don't necessarily see that show up in vote totals, but it affects the political balance in the country.

Brian Beutler

I don't know. I'm like you'd have to duplicate the United States and make a new one without a Fox News and without the Schlaflys and you know, like the billionaires who are giving over fortunes to make sure tax rates stay low and saying "any reactionary politics you have to engage in to win that fight, just do it." I agree with you that it's very potent and it makes breaking out of the 50-50 rut very hard. But it's Republicans trying to hang on to the 50%, and that making it difficult for Democrats to get to 55 or 60.

It's not like Republicans are experiencing a big growth benefit from that. You know what I mean? And so I do think that if you could just stop, reset, realign and then hit play again on the United States with a European center-right type Christian, a lot of the Romney-Clinton type voters would go back to the Republican Party, but very few Obama-Trump voters would join the Democrats.

David Roberts

But it's all these poor, you know, high school educated, white, working-class voters that came out of nowhere to vote for Trump. They were not previous voters. The question is whether they would just go back under their rocks or would they continue voting for the best they could get.

Brian Beutler

Yeah, I don't, so I don't really see myself as having a zero-sum argument with people who think that policy is the main lever Democrats can pull to optimize their odds of winning. I think who are the Democrats who overperform in states or districts where Democrats shouldn't be doing well or whatever? And I think that they think that they all look like Jared Golden, and I just don't think that that's true. They look like a lot of different things. Some of them look like Jared Golden, some of them look like dynasts, like Joe Manchin. Some of them, though, look like John Tester and Sherrod Brown.

And they're just better at seeming like they have personal integrity and they don't take a punch without swinging back. And they have this kind of like, "throw the bums out" mentality about Republicans.

David Roberts

So much of it is affect.

Brian Beutler

And like get that stuff right and then we can talk about what is the perfect policy. Do you think that a hypothetical, like a median voter or a very typical voter is going to think that you're moderate because you say, "let's all work together?" Or do you think that they're going to think that they respect you because when someone kicks you in the nuts, you kick back?

And my experience of life is that the best way to make friends and influence people is to act more like that than always turning the other cheek and entering a defensive crouch. And they have this very literalist view of what capturing the middle is. It's like you measure the middle and then you build a contraption that can fit around it perfectly and then it is captured and now those voters will like you. But that's not how humans are, right? They're not like tallying up.

David Roberts

And especially the people who I would say are closer on the personality spectrum to the authoritarian, reactionary personality, right? Like that's a big, broad spectrum. You have sort of like Trump at the one far, far end of it, but there's many, many varieties. But that personality so much operates on the id, so much operates on this subconscious level where if someone kicks you in the nuts and you respond with a policy argument that just looks like weakness, like there's a signal sent there that's nonverbal. And so much of politics is this nonverbal sort of non-propositional, id-related work.

And I feel like the problem is that, and this is one area where all these people who think that the left has become captured by these sort of highly educated, white, upper-middle-class people, I do think has some purchase in that those kind of people project what they would want to hear, which is rational persuasion. Right? And they think, "if someone just came along and told me, we take vaccines in this country, you have to do it by law. Fucking line up." that that would be awful, you need to change people's minds. But I feel like they don't recognize that for a lot of people,

and this is like something I get a lot of criticism for saying publicly. But here we are at the end of a podcast, probably nobody's listening, so I can just say it. Which is like, a lot of people respond better to that. Just to force and strength, just to certainty, right?

Brian Beutler

It's a foregone conclusion that you're going to get jabbed, so just get over your reservations. Yeah. So I think something kind of happened in parallel to the Netroots thing. But also, I think maybe has some roots in the Netroots thing, double roots, which is and I'm working on an article about this that will probably land as this podcast does, but the Netroots thing prefigured a quant takeover of liberalism and the Democratic Party. And it used to be that I think Democrats would use the word science as a cudgel, to basically signal to the public, like, Republicans are medieval in various ways.

And mostly this has to do with climate change, but it has to do with all kinds of other things. And we are the party that trusts science and believes in science. And I think that at the time and even to this day, it's a good signaling device. But I think at some point it actually became a totalizing part of the liberal identity.

David Roberts

Yes. And it became, as efforts to quantify politics always do, largely aesthetic. Right. Because in actual fact, politics is full of people and people are very hard to quantify.

Brian Beutler

I want good quantitative methods brought to bear in politics and policy, but I want people who are numerate to be doing the analysis of what that means. And it's like —

David Roberts

You see all these articles flying around like, why did SBF fool so many people? Right? Sam Bankman-Fried into —

Brian Beutler

Oh, man, this. Is in my article. This is in my article.

David Roberts

Why? Because he's got that affect. He's a white guy. He went to good schools. He talks in a certain tone and manner. He uses numbers as though he's a numbers guy and doesn't have any social graces, which makes him seem like this sort of maladapted genius. He hits all the affective aesthetic marks. And that's what most people who think they want quant in politics, that's what they're falling for is the aesthetics of precision and being a super genius who's not a dumb partisan like all the others. But there's no correlation between that aesthetic and accuracy and value, right?

Brian Beutler

But it wouldn't matter so much. It would just be this small band of reasonableness people who throw around numbers a lot, like talking to each other on the internet. Except that people have sold Democratic politicians and their election committees on the idea that these races are highly scientific. Like running an optimal race is really a matter of plugging some stuff into a computer and doing what the computer says, and it's just not the case. And we go back to the politics is a lot like high school thing. Like if you try to make friends by plugging in what you think people want to hear into a computer, or plugging in numbers into a computer, and it spits out what the computer thinks people want to hear, and you go into high school and you read those things, you're going to get a wedgie.

You're going to get a great big wedgie. But politicians are not particularly numerate and they believe this stuff and it has, like, I believe, infected Democratic politics very deeply and very detrimentally and I want them to be using numbers well. It is worth knowing if a policy polls at 20% because if it does, that's probably really toxic. And even if in your heart of hearts you think it's right, you should make your peace with not talking about it. Okay? But that's like a guardrail that's at the very edge and you can move between those guardrails all you want.

You have a policy that polls at 45%, okay? Just figure out a way to talk about it that sounds positive. You're going to be fine. It's really not that big a deal.

David Roberts

There's a lot of looking for their keys under the streetlight type of things going on in that whole field of political science and social science around elections, which is just like there are certain things that can be measured, right? Numbers of votes or whatever or demographic characteristics. And so you go measure those and just come to your conclusions about those and assume that those are the important things. But there's all kinds of stuff that you can't measure going on around that that you're neglecting. If you just are measuring what can be measured, if you're just measuring people's responses to policy proposals, then you're going to read that poll and go, "oh, what people really care about are policy proposals."

But no, that's the assumption. That's the assumption you brought in.

Brian Beutler

It also just sort of presupposes that ambient conditions are going to be the same from when you conduct the poll to the election. But you don't know what's going to happen. I mean, if you are so hidebound to what the polls say about policy or whatever and then something weird happens right before the election, you're not going to be well primed to capitalize on it if you can. Or defend yourself from it if you need to. Because you're going to have one playbook, and it's the one that the computer said was the right one. But I remember 2014 very well.

This is another election that left a big impression on me. It was the election where Democrats lost the Senate and thus eventually the Supreme Court. So it was a big deal and it was like for most of the election, basically a dead heat. The economy had recovered most of the way from the Great Recession, and Obamacare had been implemented. So the horrors of healthcare.gov were in the rear view and like Obama was entering his lame duck phase so he was more like freewheeling and I think he was doing fairly well in polls. And so the election looked like it was going to be a jump ball, which is really good for the incumbent party in the midterm.

And then there was an Ebola outbreak in West Africa and Donald Trump, actually then still just a TV game show or whatever guy, and the rest of the Republican Party, they didn't stop to consult the polls. They were just like Obama, Ebola, terrorists across the border with Ebola. That's what's happening in the world right now and you should be scared about and like you can go to Real Clear Politics or whichever poll aggregator you want and look at the generic ballot in that midterm. And right when the Ebola thing happens and Republicans demagogue the hell out of it, that's when the polls split and Democrats lose that election in a landslide.

It was just that. That's it. Obviously, I'm not saying you have to wait for an Ebola outbreak to have a successful election, but you have to be nimble.

David Roberts

Right. Things like that happen all the time, and you need to be prepared to pivot and attack on those things that come up —

Brian Beutler

And you have to have some intuition about whether you're on the right side of it or the line you're going to take on it is going to appeal to people and make them want to vote for you. But like Donald Trump sent his supporters to sack the Capitol. And there were brave Democrats like Jamie Raskin and Ilhan Omar in hiding in the Capitol complex. And they got to work drafting impeachment articles right then and there with, I think, their idea being, "we're going to finish this election and then we're going to impeach the bastard," which was the right instinct.

And Nancy Pelosi adjourned Congress and I to this day have every reason to suspect it's because she was worried that if she didn't adjourn, the push for impeachment was going to boil over before they'd had a chance to focus group it or poll test it. And she didn't want — I don't have reporting to back it up, but it is consistent with how the Democratic leadership through the whole Trump era did everything, and that's crazy to me. It's like, just understand that you are on the right side of something horrible that just happened. And as bad as it is, you have an opportunity to use it to your advantage.

David Roberts

And the main thing is, don't go out and ask people whether they think it's a big deal. People don't fucking know. People don't have the background. They don't have the history. They don't know what's a big deal and what isn't. The way they find out it's a big deal is by you acting like it, right? So if you're going and asking them if it's a big deal right there, right there, you're sending the nonverbal signal. Well, we'll get mad about this if you guys are mad, but not if you don't want us to get mad.

Brian Beutler

Which is just like exactly. My finger here is possibly measuring the wind, but if you don't like my finger here, I'll put it away.

David Roberts

I know I can put it somewhere else. Another episode I always bring up and talk about in this same capacity is the Benghazi thing, the Benghazi hearings. Republicans had — I don't even know what they got to by the end of it, was like multiple dozens of hearings on Benghazi, which was just nothing. Which was just bullshit, right? And they did it and did it and did it. And if at any point during that, if you had asked a typical Dem consultant to advise Republicans, right, they would have said, the public doesn't really seem to be caring about this much.

Like, you're kind of embarrassing yourselves. There's a lot of other policy work you could be getting done. Just like on the traditional measurements of political sentiment, it was dumb to just attack, attack like that, like a mindless zombie. But they kept at it. They kept at it. They kept at it, and lo and behold, they found her emails, and boom, there goes the election. So polling would have told you, don't attack, attack, attack. But as you say, things come up, and if you're always geared for the attack, right, you're ready when they come up. You're ready.

Like, you're always ready to use anything that comes up for your benefit. And this sort of short-sighted, like, the immediate poll response to what you're doing is negative. Oh, well, we'll run away from it. That's just so short-sighted. Like, there are long-term plays here, long-term gains. There are narratives you build up over time that you have to come back to over and over and over again. And just this sort of, like, snapshot poll taking, it doesn't even do what it's supposed to do, which is give you a good sense of where the public is, right? It doesn't even do that.

Brian Beutler

I mean, it does for that day and that's it.

Right? But it's so shallow, right? Like I keep saying, the public just does not generally have deep-seated feelings about most of these issues.

We are living through a recrudescence of the Benghazi thing right now, and I don't know if it's going to go anywhere, but I remember when Hillary Clinton testified for 11 hours before the Benghazi Committee and everyone on the left was just overjoyed because she owned the Republicans so hard.

David Roberts

Oh, the memes.

Brian Beutler

She owned them so hard. And it's true. Like, the media coverage and the immediate aftermath of her testimony was very positive because she took it to them and she answered all their questions and made clear that there was no there there and blah, blah, blah. And this was celebrated as a big turning point moment and like a proof of the theory of Hillary Clinton. It didn't stop Republicans at all. They just kept hammering away at it, kept right on. And like, there is a similar kind of self-congratulatory thing happening right now. And I mean, I'm glad it happened, I guess, because it's better that it happened than it didn't.

But the witnesses in the Republican impeachment inquiry, which they admit is they only launched so that people would think Joe Biden did something bad. They brought in witnesses who are like, yeah, there's no corruption here, or the impeachment. This doesn't merit impeachment. And everyone's like, well, there it is. The referees showed up and they spoke and they said, there's no corruption and this doesn't merit impeachment. And so you lose by the rules of the game, but they're not going to stop. And it's because they know maybe there's a 2% chance that they find a thing that is actually incriminating or that they can rip out of context to make —

David Roberts

Or just looks that way, right? Or just looks that way mildly. It doesn't have to be anything.

Brian Beutler

And if that happens, then the election's over and Donald Trump wins again, and we'll be happy. And so they just do it. And I don't admire that they do it based on bullshit, but I admire that that's how they think about —

David Roberts

They are always advancing their political interests, always at every juncture, in every decision. And every principle is subordinate to that.

Brian Beutler

That's really all I wanted from Democrats from, like, 2019 to now. Why isn't there like a pound-the-table public inquiry about Jared Kushner and Donald Trump and the Saudis? Yeah, just do it. Just do it. Why not?

David Roberts

They just sit back. They sit back and wait for the mainstream news to cover it. They're like, "this is a big deal. Please go cover this." But the way to keep that in the news is to talk about it. Talk about it, have hearings on it, even if nothing practical can come out of the hearings, right? Even if there's no obvious tangible policy or regulatory goal or legal goal. Even if the only point is just to talk about it. If the media is talking about that, then they're not talking about something else, right?

Brian Beutler

Yes.

David Roberts

If they're talking about that, then they're talking about something that works for you.

Brian Beutler

If you want the agenda to be something, set the agenda at that thing and things will fall into place. David, I promised at the top of this that this would be an hour of waxing nostalgic and vigorous agreement, and I think we've delivered.

David Roberts

We're killing it. Okay, final question, because we're over our time, but I did want to address this subject, which is probably we could do a whole another pod on, but journalism. What is wrong with it? Journalism. So I sort of have one foot in politics and then sort of one foot in this kind of technocratic analyst, entrepreneur clean energy technology. Let's use models and replace all the dirty energy with clean energy. This very kind of technocratic minded group of people over here, and then one foot in politics. And in my experience, the technocratic minded people recoil from the kind of discussion we've been having, recoil from the whole idea of, like, "oh, this team and that team, red team versus blue team.

It's all so silly and base somehow." And they have this image in their heads which so many people on the center left seem to have instinctively so many well-educated left people have in their head, which is that partisanship in and of itself is endumbening. Right. It makes you dumber. If you choose a side by definition, then you lose the ability to step back and see the bigger picture. So it's like partisanship is distasteful almost by definition for a lot of people, even though I think the vast majority of them in that world, if you pinned them down and said, "hey, do you want to create a decent social safety net?"

They would say yes. In policy terms, if you pin them down on their positions, yes, they are on the left. Yes, they are on a team because the other team hates all those things and wants to destroy all those things and wants to destroy those people. Right. Like the other team hates their fucking guts and they're sitting back saying, "eh team sports, I don't want to bother." So the way this translates in our particular case is a lot of people want to think if you are a partisan, if you have decided that some things are bad and some things are good, one of the parties is trying to fuck everything up and take us to an authoritarian nightmare.

And the other party is like fitfully, weakly, half-assedly resisting a little bit, then you can't do good journalism, right? You've lost your quote unquote objectivity, and you can no longer do good journalism. So just tell me, especially after 20 years of doing it, how you think about the relationship between, on the one hand, partisanship and on the other hand, journalistic virtues.

Brian Beutler

Yeah. So, what I don't think is a journalistic virtue are indefensible professional habits or mental habits that are meant to create the impression of fairness, but they're actually not rooted in anything real. They're just kind of made up, and it creates a lot of bad quality political journalism. And it's almost all just in the realm of political journalism.

David Roberts

Yeah. The aesthetics of fairness.

Brian Beutler

Yes. I wrote an article for Crooked Media several years ago now about how media should embrace its liberalism. But I had in mind, like, the small L liberalism. And the things about journalism that I think are important and that I bring to my work are the ones that are if you make a mistake, you correct it. You try to understand the whole range of facts before you write about it, if only to avoid making the kind of error that then because you're a liberal journalist, you feel impelled to correct. Right. That you write with precision and that you're not engaged in a sort of propaganda enterprise where you intentionally omit things that are inconvenient for your argument.

You're kind of like steel manning your argument. You're looking for what you think would be the best objection to what you have to say and sort of prebutting it, but you're doing it without putting a lot of spin on the ball about what that objection is or trying to make it look ridiculous. Those are the kinds of things that anyone can do, even if they're partisan.

David Roberts

Right. And the awareness that you might be and probably on some timescale are wrong.

Brian Beutler

Yes. It's so funny because yeah, it's like the political journalists who are mostly, like, on cable news but also write for the political desks of the Beltway Press or the New York Times or wherever else, they have this disdainful thing about anyone who chooses a side because they're just doing team sports. But then the writing is basically like, "whoa, isn't this team sports thing really exciting?" None of the things that those people think that they're doing with integrity are incompatible with having an ideology. They're not.

David Roberts

You don't have to be like Peter Baker who swears that even his family doesn't know what his opinions are. And you mean this is a little mini rant, but I've met lots of — you know I used to hang out in DC a lot more. I used to meet a lot more of these types of journalists. I used to hang out a lot more with journalists. And one of the things you find is, and tell me if you think this is true too, is people like Peter Baker who go through their whole career explicitly and deliberately refraining from forming opinions, consequently become very bad at it. Like, if you get them in a bar at night, late night, get a few drinks in them and get them to actually talk about something substantive.

What you find is, like —

Brian Beutler

Mush.

David Roberts

a stunning degree of sort of naivete and mush because the way you get good at having opinions is by stating them and arguing about them and refining them in response to feedback. And so these people are supposed to be the sort of most sophisticated, right? Because they're in the game, they're insiders, but in fact they're so clueless about the larger picture and so clueless about policy that they're like naifs. They're like some of the most naive people I've ever met about politics.

Brian Beutler

If you think that studious neutrality between the parties in your journalism requires you not to form opinions about anything, then you end up reporting about the parties in a way that is unable to be declarative about anything factual if the underlying fact is, in your mind, derogatory about one of the parties or the other.

David Roberts

Right. But you can get involved in arguments about who's hypocritical and who said one thing but a different thing. That's like, you can have opinions about these sort of like, shallow matters. But that's all you can have an opinion about and that ends up being actively misleading, I think.

Brian Beutler

It does. And I don't think that there's anything that would break the rules of legacy media journalism to throw that model out and to report on US politics in a way that's intelligently, critical, or aware even of what's happening in US politics. There's this game that people used to play on Twitter where imagine this happened in a different country. If you look at how US news media reports on authoritarian takeovers of other countries, they're very clear. Like, this party believes in democracy. That party is trying to overthrow it. There is no reason why the New York Times political desk or the Beltway rags or cable news that their marquee reporters couldn't do that about Donald Trump.

And it doesn't mean that they have to be like, tribunes against fascism and on the side of the Democrats, right. It just means explain what's happening in politics accurately. But you have to be willing to accept that the accurate thing is that the Republican Party has descended into this authoritarian formation and it's hostile to democracy and it's using its power to try to warp the game board so that it at least stands a better chance of winning than pure numbers would have.

David Roberts

And it's gotten so much that way with so little veneer, like I said, that we're almost in the weird position where the mainstream journalists are more invested in cover stories that make the Republicans seem like they have some reasonable area of disagreement than fucking Republicans are, right? Like, you talk to these nutbags in the House, they don't care about appearances. They're not trying to "on one hand, on the other hand," anybody, right? They're not pretending anymore. They're like, we hate our opponents and would like to string them all up and destroy the government. They're not pretending anymore.

And yet the journalists are sort of doing it for them, sort of like rubbing the sharp edges off for them even when they don't seem to care about doing it anymore. It's surreal. So, final, final question. There's a lot of talk about the right has this giant machine at this point. They've got Fox, the biggest cable station. They've bought up all these local TV stations. They've bought up all these local newspapers. They dominate or own the social media sites now. They completely dominate radio. I mean, they've really come to dominate the media environment, the information environment.

At the very least they are, I think, of equal size now with the supposed mainstream media. And there's all this lamentation, which I've engaged in many times myself, that the Left, the Democrats don't have anything like that. They do not have a giant propaganda apparatus waiting for these affordances that come up so that they can exploit them, right? Like, that's what the right-wing media does. It's what the left-wing media does not have. Like, something comes up that they could make a big deal out of and push into the news for days and gain some advantage on and they just don't because there's just no one, like, who would do it.

So this leads to a lot of argument about what do we want to see? Do we want to see an active, pugilistic, explicitly left media that is the mirror image of right media? And then the weak-kneed "one hand, the other hand" MSM in between them? Or do we want the mainstream media to get better? Is that what needs to happen? So what media ecosystem do you think would be healthy? What would you like to see?

Brian Beutler

So, I mean, if I had a billionaire patron and he was like, "I want you to start a media company that will be big from the outset because I'm going to put a billion dollars into it," I would want a big broadcast hub like Fox. I would not want it to operate quite like Fox because I think Fox engages in a lot of lying to the extent that they end up owing like a billion dollars in damages for defaming. Like, that's a mess. And I don't think anything good —

David Roberts

That's a billion dollars well spent, though, for the billionaires. I mean, you have to admit for the billionaires, that's the best friggin' investment they've made in the decades.

Brian Beutler

I don't want like a liberal or progressive propaganda outfit that throws the things about liberalism that I care about out the window. Like, people should be honest and people should take account of facts and you shouldn't conceal things because they're inconvenient and all the stuff we just talked about, right. But I do think that you could have a big liberal network that embraced those healthy aspects of the journalism profession, like the ones that I bring to my work. You bring to your work and staff it with people who will operate in that way. Like, there are good broadcasters like Rachel Maddow and Chris Hayes who see the world clearly and can focus on what is genuinely important and beat a drum about things that they think matter, even if the mainstream media has moved on from them without engaging in dishonesty or agitprop or anything like that.

And I mean, look, those are very talented people and it's not easy to find them, but I promise you they're out there.

David Roberts

Remember when Tucker Carlson decided he wanted to create something like that on the right and couldn't find anybody, basically couldn't staff a place because there's nothing like that on that side anymore.

Brian Beutler

I said the small l liberal journalistic values are not incompatible with having an ideology. I think they are incompatible with American Conservative ideology.

David Roberts

Yes. I wrote a whole article about this, which is about the media taking sides. Like, the media on some level cannot be neutral and objective about everything. It's got to be on the side of reality, right? It's got to be on the side of telling the truth. It's got to be on the side of being fair. So if a political movement has explicitly aligned against those values, then yeah, journalism has to be against that, right? There's a certain point you can only back up so far before you've backed your way out of journalism entirely. If there is to be journalism, then you've got to stand up for that at least.

Brian Beutler

Yeah. And I mean, it's very fitful the way journalists, the subset of journalists that we're talking about here and I don't want to paint with too broad a brush. This is like people who have cable news gigs and people who work at the political desks of newspapers. It's 200 people or something like that.

David Roberts

It's not a huge yes, it's a very insular world.

Brian Beutler

The ways and times at which they do what you're talking about, it's like stand up for the concept of truth because that's supposedly what journalism is about, which means sometimes saying that Republicans lie all the fucking time. Some will occasionally acknowledge that, but there's no expectation or standard around it. And like, Republicans are at war with the vocation of journalism. Yet the journalistic class can be very defensive of the profession. Like when Barack Obama is rude to a White House reporter or whatever.

David Roberts

Jesus. But like, remember when he tried to kick Fox out of the briefing room and other journalists rallied to their defense? That was mind boggling.

Brian Beutler

Yes. And so here you have a whole political party and a political movement underlying it at war with the vocation of journalism. And the impulse to be like, well, we'll hear both sides politely tends to overwhelm the self protective "we're a guild and we won't have you destroy us" mentality that they'll apply at other times. So I think that you build a big institution where you kind of codify those things so that the programming is true, but it's also pugnacious and it also has internal integrity and won't be pushed around by people who want to destroy truth.

Like, that's a recipe for success. And if a billionaire is listening to this and wants me to start that up, I will do it. I'll bring David along. We'll do a good job.

David Roberts

Please don't make me manage anything.

Brian Beutler

You know, I don't think that you could retrofit an existing outlet into something like that. You know, if outlets are going to evolve in that direction, it's going to be by attrition. It's going to take decades —

David Roberts

How would you advertise —

Brian Beutler

Be people from our generation. How would I advertise it?

David Roberts

What would be the public facing? Because CNN has been in the doldrums and the only thing they can ever seem to think of to do is to double down yet again on being straight down the middle. It's the only reform they seem to think possible. You're trying to get away from that. So what would you tell the public that your news would you talk about it as though we are coming from the left but we're committed to fairness? Or would you talk about it as though we are simply journalists telling the truth? Like, would you frame it as a left thing?

Brian Beutler

I don't know that this would necessarily be the tagline, but I would just say, like bearing witness faithfully, that's the whole mission. And you don't necessarily need to say that you're of the left, although that will come screaming through the programming.

David Roberts

Fox will make sure everybody —

Brian Beutler

Fox could — got away with "fair and balanced" for a couple of years. But I guess the risk in all this is that you don't know what the future holds. And I think a model like what I'm describing would be successful for this period of American history, but it might not meet the moment in five years or ten years. And then you might have a defunct cable company or something like that.

David Roberts

Are we even going to have cable in five years? I mean, who knows?

Brian Beutler