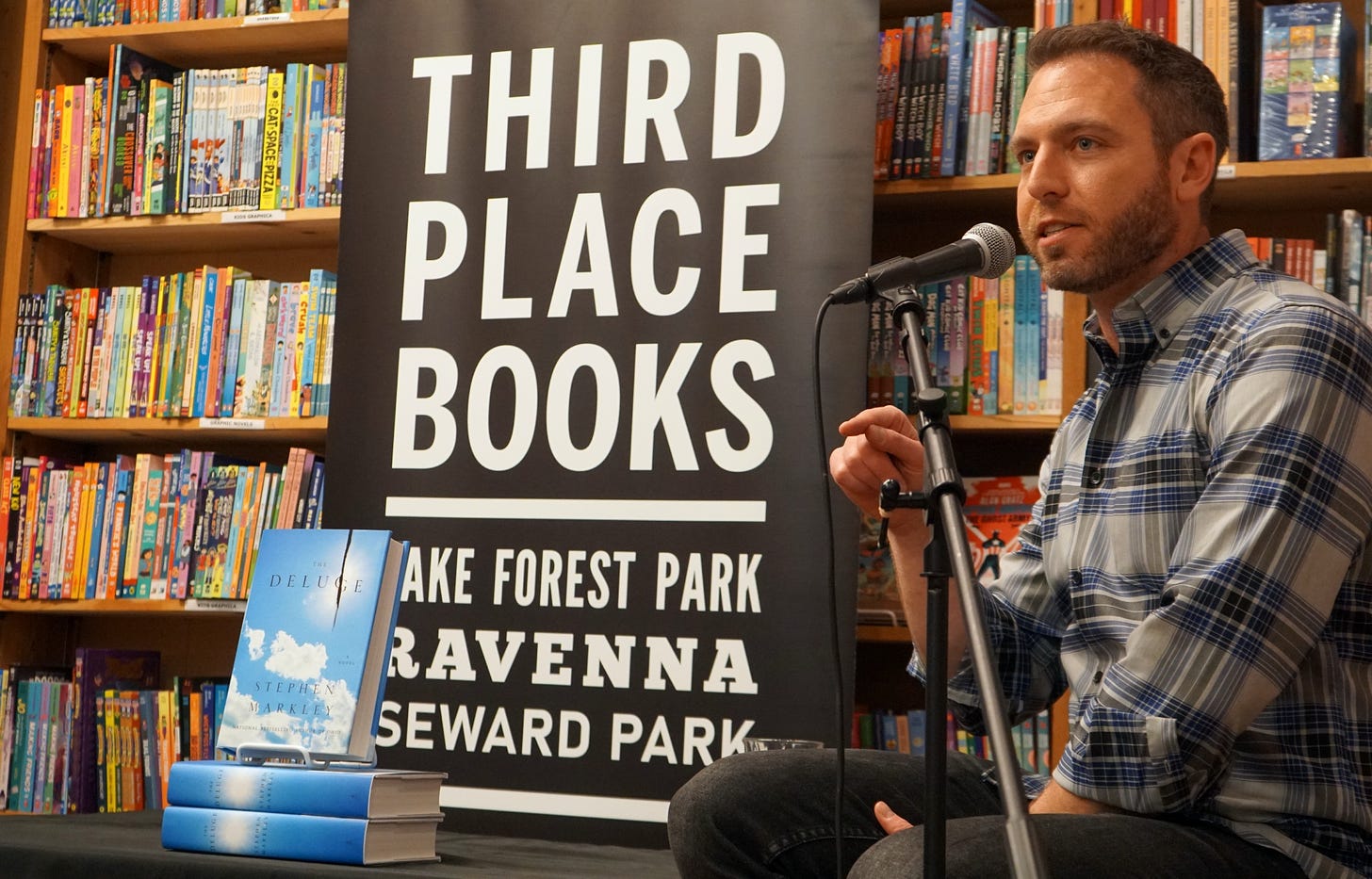

In this episode, author Stephen Markley discusses his new novel, The Deluge, which describes a future affected by climate change that hits uncomfortably close to home.

Text transcript:

David Roberts

In 2018, author Stephen Markley won near-universal critical praise with his debut novel Ohio, a tight set piece that takes place over the course of a single night, as four high school classmates reunite at a diner in their northeastern Ohio hometown.

“Four characters, one night” is pretty much the opposite of Markley’s sprawling new novel The Deluge, which tracks dozens of characters over the course of decades, from the 2010s out past 2040, everyone from climate activists to scientists to political operatives, as they suffer the effects of climate change (there are some quasi-biblical disasters) and struggle to marshal the political will to address it.

The novel crucially involves climate policy, reactionary backlashes, and direct activism, among other topics of great interest to the Volts audience.

On Thursday January 12th at Seattle’s Third Place Books, I was lucky enough to talk to Markley about the genesis of the novel, some of its major themes, and the difficulties he faced in writing it.

The crew at Third Place was kind enough to record the event (thanks Spencer!), so I'm happy to bring it to you as an episode of Volts. Please enjoy, and while you're at it, do the smart thing and buy copies of The Deluge for all the readers in your life.

Third Place Books Staff

Please join me in welcoming Stephen Markley and David Roberts to Third Place Books.

David Roberts

Where to begin? I'm just going to jump right in asking Stephen questions because I have nothing interesting to say. So, I've been writing nonfiction my whole life and have thought periodically about writing fiction—like every nonfiction author does—and even took a while one summer or one time when I had some time off to sort of sit and stare at the screen for a while and think about doing it. I had kind of a plot for a near future quasi-scifi thing, and there are tons and tons of reasons why I very quickly concluded that I was not suited to writing fiction.

But one of them was the one I still think about, which is just: "What does the near future look like?" And the more I thought about that, the more I thought, "Boy, I have no idea at all what the near future looks like." I mean, I guess you could say that at any time in history, but it seems like particularly now, there's just so much crazy shit going on. It's really like, how is it all going to interact and play out? And I found myself completely daunted and shut down by that problem.

So here you are. You have decided to start a novel basically two years in the past, and then literally just detail what happens—not in some fictional world or some far off world—what happens in this world among these people in this country over the next two, four, six, ten years in detail. And that just strikes me as just, like, fictionally speaking, the highest conceivable level of difficulty that you could set yourself. Why do that? In the book that we talked a little bit beforehand, you were thinking about even before Ohio, it just seems like the hardest thing you could do. Why not write a couple of easy books to start with?

Stephen Markley

Yeah, it all breezed by. It all went super easy and nothing surprised me. Yeah, it just came pouring out with no...nothing got in the way, historically or politically, that made... Yeah, no, it was an incredibly high degree of difficulty for the reasons you said. And all the problems of writing a 1,000-page novel, combined with the problems of it has to feel absolutely realistic at the moment of its publication. It has to feel as if it's our world sliding into this next world, right. At dinner, we were talking, I started the book in 2010, at roughly the same time as "Ohio," had to set it aside when "Ohio" was published, and then came back to it in 2017. So in that time, I don't know if you guys heard, a game show host actually got elected president. And so, the terrifying presidential character I was returning to was suddenly really unrealistic in his bombasticness. Because, like the real thing was much...

David Roberts

There's a relatively muted fascist president in your book, looking at it from our present vantage point.

Stephen Markley

I mean, look, it was a mind-blowing project for me because I had to keep paying attention to every little detail of what was happening in climate, technology, politics, our society. And unfortunately, I had found the right veins, clearly, just in terms of how our politics were developing. And that just felt like it accelerated so quickly. And then with climate policy, I think that was another, sort of, murky issue. You've talked about on your podcast before, where there was this dead period after Waxman-Markey failed in the Obama administration, where it felt like everybody was throwing up their hands. And I think that was a tough place to be to...like thinking about the future of where policy would head or how it might develop.

David Roberts

Yeah. And speaking of difficulty, sort of as you're writing and finishing, finally, Democrats are back in control and coming back to climate policy and debating the Build Back Better bill and then, specifically, the climate bill and, specifically, during that exact time period you were finishing, Joe Manchin was noodling around...

Stephen Markley

Prevaricating, let's say.

David Roberts

...prevaricating and noodling around and making everybody wait and wonder. And it was just wildly uncertain right up until the day he woke up on the right side of the yacht, I guess, or whatever happened. But right up until that day, it was just wildly unclear what was going to happen. It was a very big, sort of, historical pivot that was on the line. And it literally...that historical pivot took place during the years covered by your book. So, did this keep you awake at night, the course of actual events?

Stephen Markley

Yeah, and I mean, in a way, when it passed, I was like both sobbing with relief and pissed at the Democrats. Like, "You should have let this fail so my novel would make more sense." Actually, what happened was I had fourth pass, like the last pass in my hands at the moment Joe Manchin was like, "I'm out on this bill. It's not happening." Right. So I send the book off to the publisher. I'm listening to people, like, cry on podcasts about our dark future, and then the bill passes. So what is going to be the case in the next edition?

There are some key sentences that will be changed to reflect the reality of the Inflation Reduction Act passing. So this is just a way of me selling more books. You got to get the first edition and then come back to the next edition and buy that one too.

David Roberts

Yeah, that's wild, it just goes to the difficulty, like I said, you're writing about things that are literally happening as you're writing them.

Stephen Markley

But just to add to that, there was this sense, though, that people were paying attention, understood the Democrats would pass a mostly carrots package if they could get the chance. There wasn't going to be a price on carbon, there wasn't going to be any standards. It was going to be something where we're just going to toss as much money as possible at decarbonization. And so I think having that in mind, I could at least sort of point the direction of what would happen in the Biden administration. Although I do think the language in the book is currently unfair to the enormity of that policy that got passed.

David Roberts

I actually had that thought and then I remembered, like, "This is a novel." So, the other thing that you have to worry about in the real world is, of course, science and climate science. And this is something else that breaks my brain when I think about trying to do what you did, which is fictionalize it. Because if you are of an analytic mind, you follow climate science. Climate scientists, like all scientists, will say, "Here's the range of things that could happen," right? "Here are a set of error bars, a set of probabilities." And if you go to a scientist and say, "Well, here's what's going to happen. There's going to be a storm X big in 2029 in August." They'll just be like, "You're insane" if you try to...from a scientific point of view, it's crazy to try to say, "This particular thing will happen instead of that particular thing." So how much did you let kind of a worry about scientific plausibility...because the weather plays a huge role in the book. It's a big character throughout the book. There very key weather events.

And how much did you let it worry you whether those particular events happening on that particular schedule were plausible to scientists? Like did you do a lot of going back and forth with science?

Stephen Markley

Yeah, I did. And I think what I landed on is: I'm going to take the edge events as far as realism...to the end of the line, particularly with some stuff happening in Los Angeles and a storm that comes towards the end of the book. I think for me, it was like, "could this happen?" Not, "Is this probably going to happen." At the same time, you guys live in the Pacific Northwest, there was a heat event here a few years ago, and there was a quote by this guy's studied at Lawrence Livermore, I think, which was, "This event was impossible without climate change. It also was impossible with climate change." Like, it broke the model, the heat storm in the Pacific Northwest in '21. And so I think—and correct me if I'm wrong—we're continuously seeing is events outpacing the models that I find that particularly frightening.

David Roberts

Yeah, and that gets to the difficulty of trying to pick a particular course of events, because even now we're being surprised and we're still in early, early stages of all this. The other big thing that gripped me throughout the novel, and it comes back and forth and up and down through the whole novel, the sort of the novel, insofar as it has a main character, is centered on an activist who gets into first, activism. There's a lot of activism working with politicians and trying to craft bills and create coalitions. And then there's a whole, sort of, other splinter of activism in the book, which goes very direct action...

Stephen Markley

Andre's mom-type.

David Roberts

Yes. Which goes way down that road of direct action and bombing bulldozers and things like that. And it was interesting. This is probably not how you should read a novel, but I'm trying to squint and sort of figure out, like, "How does Steven really feel about activism and the role of activism?" I think you did a great job of certainly not coming down with any sort of pat-like pro or con, but, sort of, like there are key junctures in the book where activism screws everything up, like legitimately screws up and forestalls the possibility of good things happening.

And then there are other, sort of, the larger sweep of the book. If you look at the whole thing, like, activism clearly played a big role. So what are your thoughts on the mom...Andre's Mom question, the sort of direct action? At what point is violence against property justified? And then another question that comes up later, which is: at what point is violence against people justified? It gets bad enough that that question is thrust on the activists. So I don't know if you have...where you come down on that.

Stephen Markley

Well, I think it's important to know...the job of the fiction writer. It's, like, none of these characters can share my point of view, right? Like that is that's the path to hell. That's the path to creating a character that's just your mouthpiece, right? So every character, you have to be, like, deeply in their perspective and see the world through them. So I feel like the way the book should work is if—Shane is the character you're referring to—when you're in Shane's sections, her point of view makes sense. These mealy-mouthed activists that...they're not getting anything done.

We have to go after pipelines, right? Then you switch over to this other set of people and they're thinking, "These people are fucking it up for us. They are creating a situation in which, basically we're going to get a Patriot Act for environmental activists and so forth. So I think just also, all of those sections are about unintended consequences. And I think that's something incredibly important to pay attention to in terms of how the structure of the plot works. Whereas just because you want to do something doesn't mean the thing you're doing is going to pan out the way you think it will.

David Roberts

Yeah, I mean, even at the end of the book, looking back on it, there's still not a clear story to tell about activism was the good guy or the bad guy in the story. In a sense, everybody is kind of fucking up all the time. Your activists, your scientists, your politicians.

Stephen Markley

I write realism.

David Roberts

None of them really know what they're doing. Nothing works out the way any of them intend. I thought you captured that effect well, like, there's no masterminds.

Stephen Markley

Yeah, but I do think that there is, at least my sense of the question is that we are all trying to point ourselves in the direction of, like, "How do we change this? How do we fucking turn the ship? At least a fifth of the degree here, fifth a degree there." And so, in the end, I think all of these characters are pointing to the way in which the ship was turned by those incremental degrees. And even if many things backfired and many things didn't work, and the consequences were sometimes very scary or horrific, it's like trying to look at the aggregate of what has happened and how to change the situation.

David Roberts

Yeah. It's like the aggregate that comes across. And even with the sort of benefit of hindsight, have finished the book, I'm still not sure I could go back and say to any one of the characters, "This is definitely something you should have done, or this is something you shouldn't have done." It's not even clear, even in the context of the novel, what ends up actually causing things to happen. It's just sort of like, things grind on around, which I thought is a very realistic...as someone who's seen people cast themselves on the shore of these efforts over and over again and nothing work out and lose hope. In a sense, it's hopeful. In a sense, it sort of gets at what's so frustrating about all of it, right?

Stephen Markley

Frustrating being...

David Roberts

There's no A to B causation.

Stephen Markley

Yeah, no, absolutely.

David Roberts

So, the third sort of theme of the book that felt like it was written just for me, stuff I think about constantly is the role played by sort of far-right reactionary backlash. And I was so glad to find that in the book. There's a lot I can't predict, but the one thing I feel pretty sure about is that insofar as efforts to deal with climate change get some muscle or some seriousness, there's going to be equal and opposite reaction worse than what we're already seeing. Speaking of things being ahead of our schedule. So how do you think about it? Do you think that's inevitable?

Stephen Markley

100%. Yeah, I think death taxes and reactionary backlash are the only things we can be certain of. One of the things that has bothered me sometimes about, anything you watch on TV with politics, anything you read, any fictional setting, is the de-politicized nature of it. That's incredibly irritating because we live in an incredibly politicized environment. So, my only goal with the book was to, sort of, not to write it from the guy who voted for Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden's perspective. This is not, again, my mouthpiece. It's like, how can politics develop, surprise us? How can they swing around in ways that we don't see coming now, but might happen in the future?

And so there's a character, a Republican president who wants to do something about climate change. There's a Democrat who behaves like a monster. There's all that stuff, sort of, in the way our politics now continues to shock us, like making sure to keep the reader off balance, right?

David Roberts

Yeah. I got to say, that Republican president doing something good on climate change.

Stephen Markley

I knew you would hate that. Even as I was writing it in 2015, reading David on Vox, I was like, "I know he's not going to like this. When he finally interviews me in Seattle."

David Roberts

That was the one time where my eyebrow went up. I was yeah, and then, of course, everything falls apart on her. I was like, "Yeah, that makes a lot more sense."

Stephen Markley

You see what I was doing.

David Roberts

Everything falls apart after all. Another big question—I'm hitting you with all the big themes here—is, again, maybe you try to keep your point of view out of it and just put a lot of things in people's mouths. But the net effect of the book is a critique of capitalism, basically. This idea that climate is not isolated, unique, technical problem. It is an outgrowth of the basic way our socio and economic system works.

Is that you? How much of that is you and how much of that is activists?

Stephen Markley

I think if I had to distill my critique of the world into a few sentences, yeah, that would be somewhat difficult, but I think what climate represents is it's not just a crisis of, "oh, we're doing this or doing that wrong." It's like there's a lot wrong with our system that we do recognize, right? And so, as you often say, the point of solving the climate crisis is not just so we can fly around on private jets and keep the world as this inequitable and this miserable. The solutions to the climate crisis point the way forward into actually changing the world for the better in many, many ways.

And what I think your podcast does so well is explicate that. I'm going to use this little moment to talk about this guy just because...no, you have to suffer through it, you just have to.

David Roberts

Turn off his mic.

Stephen Markley

No, because I started reading David before I even started the book, when he was at Grist and he was one of the first climate writers I encountered who had such a clear-eyed view of the issue and, sort of, left the moralizing elements of it to the side. And since then, basically a David Roberts' completist. Like, I've been reading him the entire time, even when he went to Vox for the down years.

David Roberts

This is very embarrassing.

Stephen Markley

No. But anyway, you should check out Volts if you haven't. It's an incredible podcast. When he brings on people who talk about how we solve this. It's like one of the few moments in my day when I'm like, "Okay, there are a lot of smart, passionate and incredibly just intelligent people working on every element of this problem." And I think that's something to keep in mind when we talk about this really scary thing.

David Roberts

Yeah, it's actually...one of the things you didn't get into that I wondered about was the role...like, one story people tell now about how this is all going to play out is that clean energy is getting cheaperly fast and the markets, people are going to start opting for these things for market reasons and basically, like, the cleverness of innovators and entrepreneurs are going to turn markets for us and save us from ourselves. There was very little of that in the book, I take it you just don't credit that.

Stephen Markley

No, that's not quite the case. I think the whole experience of writing it, that was not happening yet, or it was happening, but it was like slower. It's really turned up in the last few years and so for me, it was just like, no introducing geothermal energy that suddenly solves all our problems. I couldn't slip that in and pretend like this is going to be the solution, even though, who the fuck knows, maybe it will.

David Roberts

Who knows?

Stephen Markley

Right. So, I just think that was an element of the book that, sort of, I was not eager to shove into it. At the same time, I have become more excited about the possibility that stupid capitalism is actually on our side, suddenly.Aand at the same time, I do feel like these incumbent industries, fossil fuels, are going to put up a way more voracious fight than a lot of people are thinking about right now.

David Roberts

Yeah, one of the striking things about your book is they don't quit. The Eastern seaboard basically gets flooded and they still don't quit.

Stephen Markley

I mean, look, they're going around I would listen to that podcast with what the gentleman who was talking about...they're going around to a bunch of communities trying to gin up resistance to clean energy that will benefit those communities. And they're just really good at it.

David Roberts

Yeah, they are good at it. So, I want to get to audience questions before too awful long, but speaking of—this kind of gets back to the capitalism thing—sort of at the end—if we can do this without spoilers—you could have, very easily, I think, and very plausibly, ended this with sort of everything falling apart and everyone dying. Just, sort of, like dissolution on the horizon as far as you look, and that would have been 100% defensible. So how much did you...this is like the most cliché question in the world.

Stephen Markley

I can't wait.

David Roberts

How much did you worry about, "Do I want people to throw themselves out of a window after I read this book? Or to what extent do I need a happy ending?" Insofar as you can call a story where hundreds of thousands of people are dying and getting driven out of their homes and migrating and whatever else, happy.

Stephen Markley

Right, but we're in this very bizarre situation now where we're talking about stopping the heating of the planet at two degrees is the happy ending, which seems insane. And so I guess the book, without spoiling anything, the book lands on a knife's edge, right. It's pretty much exactly what we're looking at right now, which is: we have every tool we need to rapidly decarbonize the global economy. We could be growing much faster. Some of the terrifying results are already baked in because we waited too long and it's going to be, you know, the fight of several generations to turn this thing around.

And I just think, like, the book ends as really that effort has gotten underway at the scale that it actually needs to affect the correct change, though.

David Roberts

Yeah, it takes quite a few body blows before that comes around. Another thing, I really appreciate it in the book, I felt this about, "Don't Look Up 2" the movie. Anytime you tell me a work of fiction is about climate change, I go in pre-grimacing and do it completely tensed up.

Stephen Markley

Me too.

David Roberts

Completely tensed up stuff, watching for...it's, like a doctor watching ER or whatever. You catch all the little things. But one thing I was glad you didn't do is this notion that once a disaster is big enough, right. Once there's a spectacular headlining, grabbing enough disaster, it's like a shock. And then everybody is like, "Oh, you're right, we do need to do something about this." And everybody swings around and gets supportive. And as you show in the book—show rather than tell, which I appreciated—it causes some people to do that, but it causes just as many other people react to trauma with fear and nativism and nationalism and anger.

Stephen Markley

I think the most important thread in the book is, there's one of the sections is called "Feedbacks." And feedbacks, we all know what climate feedbacks are, but the most important feedback is us as humans is what are we going to do? And unfortunately, one of those feedbacks is the worse things get, the more of that starts to come out. And it's just even more reason to arrest this as quickly as possible because those effects will accrue that kind of resentment, nativism, hostility. It's so inevitable. And so I think making sure that was ever present in the book was, sort of, a key thematic aim.

David Roberts

Yeah, there's a president who runs on...this is something I've had in my head for a long time. A president who runs on like, "We need to put up big walls to keep all these migrants out, and we need to hoard our fossil fuels and dig up all our fossil fuels."

Stephen Markley

Carbon maximalism is the name of the...

David Roberts

We have an island here, a walled island, and we're protected from the rest of the world going to hell. And of course, it doesn't and can't work, but 100% plausible that someone...

Stephen Markley

2024 will probably bring about that candidate.

David Roberts

Yeah, you got to wonder.

Stephen Markley

You're shaking your head, but, y'know.

David Roberts

Okay, well, I want to hear from y'all, so if anyone has questions, please. The question was, "How far out into the future does the novel go?"

Stephen Markley

It ends in the 2040s, so it starts in our recent recognizable past, 2013. So we get like, a taste of where we've all been and then ends in the 2040s.

David Roberts

Yeah, it really is like present day, you're familiar with, marching right forward to your tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. It's very disturbing in that way...how smoothly it goes from a very familiar situation to things going fucked up in sideways in all kinds of ways.

So the question is about this perpetual argument in the climate space over individual action and individual responsibility versus structural infrastructural political changes. And as a god-like narrator, you get to choose which of those works more in the end. Did you have that in your head as you were writing?

Stephen Markley

Yeah. There's no point in the book when flight-shaming solves anything that's actually...

David Roberts

Plastic recycling, though.

Stephen Markley

Yeah, right. I'm sure we share this sense, which is very quickly into my very basic intellectual encounter with the climate crisis, even back in when I was in college, was like, "Oh, all this stuff is like, mostly virtue signaling garbage." And that's not to say, like, people should live their lives as ethically as they can and they want to like I don't want to like, denigrate anybody who does that stuff. It's just that, like, chirping about it doesn't help anything. We really, really need to accrue political power and change things at system levels, as David often says. It's the most vital thing.

David Roberts

But what about just a slight twist on the question, which is rather than personal action in the, "Buy a hemp tote bag, drive a Prius, to..."

Stephen Markley

How to green your Netflix binge.

David Roberts

That type of thing. What about personal responsibility for activism and political engagement?

Stephen Markley

I love that and I wish that was...what do they have memes now? I wish that was a meme somewhere on the Tiktok.

David Roberts

I think they're called memes. Anyone in the audience?

Stephen Markley

Because it is. And just, you know, I was reading Hal Harvey's book, "The Big Fix," which I very much recommend, which is about this topic. And there's a story in Montgomery County, Maryland where a bunch of high school students were agitating about their disgusting diesel-fueled buses and it led to the county electrifying the bus fleet. And that seems like a small thing, but if you start multiplying that across school districts around the country, it's not a small thing. And it dovetails with the strategy that has emerged, which is electrify everything and crush demand for fossil fuels. So I think those are the sort of actions we have to look towards.

And particularly cities like Seattle and LA and all these other sort of liberals, like bastions, can go a long way in implementing policy and nobody pays attention to any of this. So a little bit of action goes such a long way. Him back there?

David Roberts

The question was, "If you, in a dark alley sometime, come face to face with a climate denier, is there anything in particular, any strategy or fact or emotional valence that you have found useful in moving such?"

Stephen Markley

Yeah, so what I like to do is get super upset and really dive into all my facts and just present them in a logical way and get angrier and angrier as the conversation progresses.

David Roberts

Don't forget footnotes.

Stephen Markley

Yeah. I pull up on my phone, articles from the New York Times and I'm like, "Wait, look, Paul Krugman says this," and that works every time and it's all fine. I think like I, you know, you don't have to say it's, like, look at the Exxon documents from the 1970s. Like they knew. tTheir scientists were out studying this. They said the world was going to go to hell if they kept doing what they were doing. So you don't have to take my opinion for it. You can go look at what Chevron had to say.

But no, to seriously, answer your question, though, I do think the tech has suddenly become this very interesting tool, which is like, anybody who has an electric heat pump—my dad won't shut the fuck up about his electric heat pump. Not that he's a climate denier. But it's like they should put warnings on that, on electric heat pumps that say, "Your dad might talk about this for a year."

David Roberts

I know. Warning to your neighbors: Do not engage on the heat pump.

Stephen Markley

Exactly. There are these ways of just saying, "you should at least try this thing out," that I think once people start experiencing this very better way of producing heat and energy, it will not move the needle on denialism, but it will at least maybe a little crack or a fisher here or fisher there.

David Roberts

Yeah. If I could just add, like, I've been at this since early 2000s or whatever, and in the early 2000s, there weren't a lot of people who cared one way or the other. So it was mostly, like, a tiny handful of us who cared and a tiny handful of jackass deniers who were paid to disagree. And I spent several years going back and forth with them and quickly realized a couple of things. One is: if you find people who are invested in denying, they're usually that way ideologically, and you will not change their mind. And the right strategy is to turn around and walk in the other direction as fast as possible.

The vastly larger problem is: poorly informed and mildly disengaged. Like, the vast bulk of people just don't know that much and don't care that much. And how to get them involved is a much, much bigger and more important question than how to turn around some jerk off.

So the question was: what was most helpful to you in your research about how to address the problem? And I guess that can...because there is just for you have not read it. To my great delight, there are some pretty weeds-y discussions of policy. There are rooms full of people discussing policy in some detail, which is just totally my thing. Again, not allowed to mention me. What sources did you find helpful?

Stephen Markley

I just mentioned "The Big Fix," which was written by this guy, Hal Harvey. He's been on...I discovered him through David's writing, but he works at Energy Innovation, which is a think tank. They were advising Congress on the IRA. And I was so grateful a person who works there read the book for me and sort of advised me on everything. And I'm just so relieved that there are people who are like, "Alright, what is step A? Let's do step A, and then we'll move to step B, and then we'll go to C."

And it's just that sort of level of thinking of, like, what are the things in society driving this crisis? How do we change them, right? I would be remiss also if I didn't recommend a book by my good friend Lisa Wells, who is here called "Believers." It is a terrific nonfiction book. I read it in the midst of writing "The Deluge" and it's like one of those books that sort of, like, made me feel what I'm supposed to feel right now in the midst of this. And I think that's, as we were saying, like, if that's a difficult thing to do, like all of this just sort of exists in this haze. And every once in a while there's in a weather event that freaks us out. But then we all go back to normal. And even those of us who care about it have a hard time sort of holding on to it. So I very much appreciated those books that I read that was like, no, no, this is keep your eye trained on this.

David Roberts

And of course, to add fiction is one of the things that can do that in a way that no nonfiction can. And sort of like reading about this scientist who's been discussing these very sort of cold, wonky things, the whole book careening through a burning Los Angeles to try to save his daughter from her apartment. It really makes things visceral for you.

So the question is about why there was so little climate fiction or art for so long, and now it seems like it's kind of bubbling up now. There's a couple of big things popping out, really big ambitious works, and whether you have any thoughts on why that's happening. And I'll say, whenever I say on Twitter or whatever, "Oh, there's not enough climate art," people start throwing obscure climate art at me and obscure climate novels. But in terms of big, popular culture stuff, really, this book is the first because you'll get lots of books that are, like, dystopic and you're like, "Oh, it's like an analogy to climate change hovers in the background or whatever." This is about climate change more squarely than any work of art I've ever met. So what do you make of that?

Stephen Markley

I think it's bizarre as well. And it's sort of in the course of writing this book, I was somewhat terrified that someone would come along and preempt me with the same thing, basically. And it never really happened. And I don't know, I might get in trouble for this, but I'll just take you through this story. I work in Hollywood now, I don't know if you saw my picture with Tom Hanks. It's up on Instagram. Okay. But we went out with "The Deluge" early to see if we could gin up interest in an option.

And I just got the same question in every meeting, right, which was basically to the effect of, like, "Well, what about the people who don't believe in climate? Like, I believe in climate change, but what about the people who don't? What's in this for them?" And I always found that, like, the most bizarre, mind-blowing thing, because when you're in it, you're like, this is the most important fucking thing to ever happen to humans. Like, let alone...

David Roberts

Yeah, like somebody proposing a pandemic movie. Like, we don't believe in pandemics.

Stephen Markley

Right? So to me, there is this weird still, and this is a testament to the power of the propaganda laid out by the fossil fuel industry. There is still, in the US especially, this sort of idea that it is this highly-politicized issue, which it is, but in a way that you can't even make art about it because it will prickle people. At least that's my Hollywood opinion. As for fiction, I think there are quite a few climate novels, but I think they do exactly what you're talking about a lot of the time, which is they're not addressing the issue, they're coming at it from allegory or whatever else it might be. And the project of "The Deluge" was like, okay, straight to the fucking eye, let's do this. Let's get every issue in this complex subject on the table.

David Roberts

Yeah, if you want an explanation for why there hasn't been, I just think because it's super fucking hard. Like, climate is everything. It is literally everything. It's every fiscal system, every political system. It's like social system, it's emotional, it's allegorical, it's everything. So, it's one thing to understand that intellectually, but fiction is all about specificity. That's what I was trying to get out of my first question. Taking all that and deciding this specific thing, that's just mind blowing to me, and I understand entirely why people haven't done it. It sounds really hard. I'm still waiting for the first good climate movie. I don't know, "Don't Look Up" did this, sort of, like, analogy thing.

Stephen Markley

Yeah, I mean, I listened to the podcast with...what's his face? Adam McKay, sorry.

David Roberts

McKay, yes.

Stephen Markley

I hope he's listening to that right now.

David Roberts

Famed Academy Award winning director, Adam McKay. I expect in coming years there will be more attempts at this. I sort of hope that, you did the sort of needful, which is like directly grappling with the horns. But there's ways to get at this through genre. You could do a horror, you could do a heist movie. You can think of lots of different ways you could weave climate change in. That's what I'd like to see is not necessarily just a ton of stuff directly about climate change, but just more ambient climate change in culture. Just sort of more of an acknowledgement that it's whatever story you're telling and whatever you're doing, it's there. It's around you.

Stephen Markley

So, David, you're telling me you have not watched the film "Hurricane Heist"? Because that...

David Roberts

I have, actually!

Stephen Markley

Yeah, see! What are you talking about? It's a classic, yeah.

David Roberts

I thought that movie was so terrible that literally no one else in the world would watch it. I'm glad you have the same appetite for terrible movies.

Anybody else?

Audience Member

But did you sell the options?

Stephen Markley

No, it's still available, Adam McKay.

David Roberts

Dear Academy Award winning director Adam McKay...

Stephen Markley

Yeah, back there.

David Roberts

So the question is: was it cathartic to write this for a decade or did you find it innervating to wallow and apocalypse?

Stephen Markley

Yeah, I definitely thought it was emotionally exhausting, and especially about at the 60% mark or maybe the 70% mark, when I had sort of set in motion the wheels of all these multi-faceted crises happening at once. And I just, like, it felt too real to myself. For me, really, like, the point when I had to shift my own thinking on it was when I started to explore, like, okay, who are the people out there actually trying to do something about this? Not setting their hair on fire, not bemoaning humans as a virus on the planet, but just like, what systems do we have to change in order to do this?

That's when I started to orient myself a little bit more productively towards the task at hand. Then it was being edited in the middle of 2020 during the pandemic, during the riot of the Capitol, like, all that shit that just seemed like, "okay, my book, it's, like, not scary enough," you know?

David Roberts

So, yeah, what about the riot? What about January 6? That happens during the time period of the book, right?

Stephen Markley

Either way, without any spoilers, the way I found out about January 6 was my friend, an early reader texted me and said, "How does it feel to be clairvoyant?" And I did not enjoy turning on the television to find out what he meant.

David Roberts

We'll leave it at that. You have to read the book. When will there be an audiobook and are you going to be involved in it?

Stephen Markley

It is available right now, and I am not reading any of it. So, you can listen to better people than me.

David Roberts

Anybody else? Yeah, go ahead. Do you get into the role of animal agriculture in climate change in the book?

Stephen Markley

A bit through one of the most vociferous characters, who's a vegan and sort of forces her partner to become one, as most vegans do.

David Roberts

Hello. There they are.

Stephen Markley

Oh, wow. It's like that spot-on or something. But also there's this moment at the end when basically a character is laying out, okay, like, what do we do? And agricultural policy, of course, plays a role in that, yeah.

David Roberts

Am I dreaming? But people aren't eating beef by the end of the book for some reason? Am I making that up? It wasn't like a policy or anything. Just like, all the cows died, or I may be making stuff up at this point.

Stephen Markley

Yeah, it's basically like the US government goes around buying up livestock and then basically shutters the industry, I think, is what you're...

David Roberts

Yes, that happens. In that sense, something quite dramatic on that.

Stephen Markley

But then you need to precipitate a crisis like in the book, and I think we need to avoid that. Yeah.

David Roberts

So this is a question about writing process, and it is a big, sprawling book. It's got lots of characters in it, and the question is, sort of, how many is enough? How many is too many? How do you know when you're representing everything you want to represent. What's the thinking there?

Stephen Markley

Have you read "Ohio"? Okay, yeah. So with "Ohio," it's like I had the four characters the whole time and knew exactly who everybody was. With this, I probably started off with ten or eleven point of view characters. And as the book progressed, it became clear, like, you're biting off way more than you can chew. And so, they began to drop away. And I think in the last edit, basically, between me and my editor, I cut one more. It was hard because when...

David Roberts

Do you know how many you ended up with?

It's seven, basically. But when you have to cut out a whole character, it hurts. It's like chopping off your arm, right? And so I think, like, that last hurdle of getting rid of...but the book had to move. It had to be, and I think it is, like, very readable, very page turnery. And I think that was something my editor and I discussed that was vital, that a book this size with this much policy and science and so many ideas packed into it, it really had to be aggressively interesting. And so a few of the characters who I thought were vital, it turns out they kind of weren't.

Stephen Markley

And once you've cut it, once it's gone, you don't miss your arm anymore.

David Roberts

No phantom pains.

Stephen Markley

No phantom pains.

David Roberts

Yeah. I just want to say for those of you who have read Kim Stanley Robinson, "Ministry for the Future", I always want to say "Swiss Family Robinson." I don't know, once I say...

Stephen Markley

That's a different type almost!

David Roberts

...like that's not It! "Ministry for the Future." "Ministry for the Future" is a very, like, it says fiction on the cover but it's, like, a little bit of fiction with a lot of, like, white papers sprinkled throughout, which is, like, great if you just want to learn. You'll learn a lot by reading it. But just to be clear, this is not that. This is an actual novel. An actual page-turner of a novel, and not just a bunch of learning, a bunch of briefs.

Stephen Markley

David Roberts. Fuck learning.

David Roberts

Yeah, enough with this learning. Thank you, everyone.

Stephen Markley

Thank you so much for coming out. I really appreciate it. Thank you, David.

David Roberts

Thank you for listening to the Volts podcast. It is ad-free, powered entirely by listeners like you. If you value conversations like this, please consider becoming a paid volts subscriber at volts.wtf. Yes, that's volts.wtf, so that I can continue doing this work. Thank you so much. And I'll see you next time.

Share this post