Hey Volters! Thanks for being among my earliest subscribers — I’ll always love you more than the johnny-come-latelys who sign up from here on out. Let’s keep that between us, though. On to some Thursday energy thoughts …

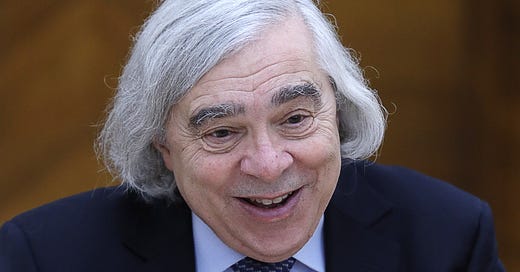

Our old friend Ernest Moniz has been in the news again lately. Moniz, you may recall, is a nuclear physicist who served as Obama’s secretary of energy from 2013 to 2017. Now he is reportedly on Joe Biden’s short list to take the position again next year.

This has drawn howls of outrage and protest from climate activists, for two basic reasons. The first is Moniz’s history of ties with the fossil fuel industry. The second is his enthusiastic support for Obama’s “all of the above” energy policy.

I’m not going to get into the first fight — I’m highly ambivalent about the usefulness of “ever worked with or adjacent to fossil fuel companies” as a guide to who would or wouldn’t be good at a particular position. A lot of smart, committed people get filtered out by that heuristic.

But as far as I know, Moniz is still all-in on “all of the above.” And readers, “all of the above” is some bullshit.

“All of the above” is a political dodge, not a substantive position

My objection to “all of the above” is that it is not actually a coherent position on climate or energy policy. It’s hortatory language, meant to exhort the listener to turn off their critical facilities and drop their objections.

Obama adopted the slogan out of perceived political necessity. He knew he needed to kick-start the transition away from fossil fuels, but he also knew that directly attacking fossil fuels was a political loser for him. There were too many Democratic senators from fossil fuel states, too many unions doing fossil fuel work, too many constituents with (or dependent on those with) fossil fuel jobs.

He was, in classic Obama fashion, trying to hold two opposing sides together, telling fossil fuel Dems that he was going to continue developing US fossil fuel resources while telling climate activists that he was going to develop clean energy. And he really did do both, overseeing an explosion of oil and gas development and an explosion of renewable energy.

He framed the goal not as climate mitigation — still seen by most Dems then as a divisive leftie issue — but “energy independence,” as in his 2014 State of the Union address:

One of the biggest factors in bringing more jobs back is our commitment to American energy. The all-of-the-above energy strategy I announced a few years ago is working, and today, America is closer to energy independence than we’ve been in decades.

Unfortunately, this just doubled the bullshit. It wasn’t good policy for achieving energy independence, because energy independence isn’t a thing. And it wasn’t good policy for addressing climate change, because, as scientists have made even more clear in the ensuing years, avoiding catastrophic climate change can only be achieved with a rapid phaseout of fossil fuel exploration and exploitation.

The both-and political strategy was arguably a success for Obama. He managed to get a lot done on clean energy without arousing the concerted opposition of conservative Democrats. But it has not left a positive legacy.

Republicans, of course, love it, and use the slogan to this day. For them it’s just a way of saying “don’t phase out fossil fuels,” which they support because they don’t care about climate change. And if you don’t care about climate change (or pollution), it really does make sense to exploit all available energy sources.

But Moniz tried valiantly to frame it as a climate mitigation policy. In a 2014 address, he said:

We say “all of the above,” but let me be very clear: “all of the above” starts out with a commitment to low carbon. … There is not going to be one low-carbon solution. There are going to be multiple low-carbon solutions. We need all the arrows in the quiver, and that is why we will continue to invest across the board in our different fuels and, of course, efficiency and other technologies.

We need all low-carbon solutions, therefore we will continue investing in all fuels, including the high-carbon ones. What now?

At a webinar for MIT’s Roosevelt Project this September, Moniz was still saying basically the same thing:

I’m completely neutral on technologies. I’m not neutral on putting CO2 into the atmosphere. Carbon [capture and] sequestration is just as good as putting in place a zero carbon technology — renewables, nuclear, you name it.

This is not a defense of Obama’s actual policy. Even if you’re committed to pursuing every low-carbon solution, including systems that capture the carbon emissions from fossil fuels, that’s not a justification for accelerating fossil fuel development and burning fossil fuels without capturing carbon. Investing in fossil fuels as part of a strategy to reach net-zero emissions is incoherent. It always was. Obama likely knew that and just lived with it as the best political deal he thought he could make; Moniz seems to have sipped the kool-aid.

Let’s interpret him charitably, though, as saying that “the above” in “all of the above” only includes carbon-reduction systems and technologies, not unrestrained fossil fuels. This is actually a coherent argument.

But when you look under the hood, it’s a quite radical argument, with implications Moniz and other fans of the slogan are unlikely to embrace.

Narrowed to low-carbon, “all of the above” is a radical stance

Let’s take Moniz to be arguing that, within the world of carbon-reduction technologies, “all of the above” is the guide — one such technology is, as he says, “just as good as” any other.

This implies some pretty strong value judgments. It says that carbon matters — the difference between carbon-intensive and low-carbon is significant — but other differences don’t.

The difference between energy sources that pollute the air and water and those that don’t; those that require intensive use of biomass or rare mined minerals and those that don’t; those that use lots of land and those that don’t; those that employ lots of people and those that don’t; those that negatively affect low-income and minority communities and those that don’t; those that empower large fossil fuel companies and those that don’t; those that are centrally owned and those that are distributed and more democratically controlled — none of these distinctions matter. None of them are sufficient to place a source outside “the above” we should pursue all of. Only carbon emissions matter.

It’s not an indefensible stance. You could mount an argument that the danger of climate change is so severe and so imminent that avoiding it should override all other proximate concerns. But truly taking that seriously, following it to its logical conclusion, gets pretty dark. After all, it’s not difficult to imagine a politically repressive low-carbon regime. (In fact I’ll be writing more about that later.)

However, even if you accept the argument that only carbon matters, “all of the above” still does not make sense, for the simple reason that carbon-reduction systems and pathways are not fungible. Any one is not just as good as any other.

Not all pathways to lower carbon are equivalent

It is true that, from the point of view of the atmosphere, a ton of emissions prevented by CCS is equivalent to a ton of emissions prevented by building out renewable energy. Physically, they are the same.

But they are not the same politically, economically, industrially, historically, or even morally. They involve different constituencies and players, different economic and ownership models, different governance and regulatory requirements, and different social, economic, and health effects that fall differentially on different people.

These differences matter! They have practical implications. Figuring them out is a whole lot harder than just comparing tons across technologies with a ton-o-meter. Physical science gives comfortingly firm answers, but questions of political economy are vexed, involving lots of conflicting instincts and intractable ideological disputes.

But still, you can’t just wave those questions away by saying “all of the above.”

Let’s focus on CCS. Moniz’s position is that there’s no reason to oppose fossil fuels as such, or fossil fuel companies. It is carbon emissions we should oppose, and if fossil fuels can be burned without emissions — if their emissions can be captured and stored underground — then they’re fine, just as good as renewables.

Put aside the fact that no CCS facility in the world captures 100 percent of carbon emissions and very few even come close. Even if CCS were 100 percent effective, it still wouldn’t be the case that emission reductions are fungible, that reductions via CCS are just as good as reductions from renewables.

Capturing and burying carbon at scale will require enormous global infrastructure, by some estimates three times the size of the oil industry. Even if all that infrastructure is built out, it will be utterly inadequate to offset the emissions of economies still running on fossil fuels.

The best-case scenario is that CCS (and direct air capture of carbon) mop up what renewable energy can’t get to, and then, after we reach net-zero emissions, goes on to draw down carbon until we reach a parts-per-million conducive to a stable atmosphere.

For that to have any hope of working, most carbon emissions must be eliminated by zero-carbon energy. The vast bulk of that work is going to be done by clean electrification: the suite of technologies, policies, and rules that will decarbonize the grid (with renewable and nuclear energy) and get cars and buildings hooked up to it.

Clean electrification is the main course. Depending on how bullish you are, it’s going to get the US anywhere from 70 to 90 percent of the way to net-zero emissions.

After that, we’ll probably need to capture and store carbon. It’s what most models now indicate. But that will be supplementary work. If we go gangbusters on clean electrification but neglect carbon capture, we’ll get to 80 percent reduction. That would be a good problem to have. We would be lucky to have that problem.

But if we pursue carbon removal and neglect clean electrification, we are hosed. There is absolutely no chance we can scale carbon removal up fast enough, big enough, to compensate for an economy that remains carbon intensive.

So carbon capture/removal/use/storage (I’m going to write a post clarifying all these soon) and clean electrification are not fungible. The latter is desperately, immediately necessary; without it, all hope is lost. The former will be needed in decades to come to supplement the latter. That implies not some breezy “all of the above” approach, but smart prioritization.

We must accelerate clean electrification. That must be the top, non-negotiable priority.

Climate policy in an age of Republican obstruction

The reason this is on my mind is the grim political situation that lies ahead. For the next two years, Republicans will have control of the Senate. They might have control for the next four years. They might have control f’ing forever.

That means no big climate legislation. Period. (Having no illusions about Republicans will be a running theme in Volts.)

This creates a dilemma. Should Joe Biden go nuts with executive action, even if it poisons the well for any possible legislation? Or should he go easy, reach across the aisle, and try to get some legislation rather than none?

As I said in a recent piece and on MSNBC, I think it’s the former. He should blitz.

People advocating for the latter (I don’t know that Moniz is among them, but I strongly suspect he is) hold out hope that Republicans will cooperate on a limited slice of climate policy, mostly CCS and nuclear (and, uh, trees). And since their assumption is that carbon-reduction technologies are fungible, this will count as progress.

But as I said, they’re not fungible. If we neglect clean electrification while pursuing CCS, we’ll be nibbling on side dishes while the main course goes uneaten. And while we’re at it, we will further empower fossil fuel companies, the primary political opponents of clean electrification, thus potentially slowing the crucial work to come. We will further entrench an already difficult political economy.

If we’re not making progress on clean electrification, we’re not making progress. If Biden has to sacrifice a CCS bill to get stringent EPA regulations on power plant emissions, he should do it.

At its root, “all of the above” is a call to suspend judgment, to ignore the social, political, and economic differences among different energy technologies and pathways. But those differences matter — they will shape how, or whether, the clean-energy transition unfolds.

We should pursue all available options, if only to build in some insurance, but that doesn’t mean we should pursue them all with the same speed and vigor or in just any old order. How we pursue clean energy innovation, development, and deployment, the choices we make along the way, will matter. In this case, as in most, suspending judgment is a bad idea.

The drvolts archive

I’ve been writing multiple pieces a week for 15 years now, which means my published oeuvre is far too vast for me to remember more than a small fraction of it. One thing I want to do in Volts is dig up old pieces, dust them off, and highlight them. Many hold up quite well, I think, or are educational in various ways. And they’re doing nobody any good sitting in the bowels of the internet.

Today’s golden oldie is from 2012. It is, if I may brag upon myself, quite prescient and highly relevant to current political debates around how Joe Biden should deal with Republicans. “In an era of post-truth politics, credibility is like a rainbow” is about the notion, common back then, that by making policy concessions to Republicans, Obama could gain credibility with them, political capital that he could then exchange for Republican cooperation.

It was wrong then, and it’s wrong now about Biden. Only Republicans can grant credibility with Republicans, and they just won’t/don’t. Check out the piece and let me know what you think at david@volts.wtf.

Pet corner

Finally, as promised, a pet picture. In my introductory post I featured Mabel, our nine-month-old rescue puppy, who we got in August.

Below is Forest, my very best boy, my companion, my heart, who has been with us for almost 10 years now. He wants to give you a shake, and thank you for reading Volts, and encourage you to share it with your friends and grow the Volts community.

Im hoping that with the cost curve of renewables and batteries, we get to a point fairly soon when market forces do the electrification prioritization for us. I think electrification of the home and transportation will be a superior, and cheaper, product than what we currently use. Of course, fairly soon could be too late.

AOTA is often the other (action vs. restraint) side of the coin of “We shouldn’t pick winners.” But that one is intellectually bankrupt for the same reasons. We spend good and scarce tax money on government programs and employees, including elected ones, so they will pick winners, distinguish and differentiate among alternatives, and guide toward the common good. It matters. Thanks, David, for a great start on the new effort!